Cette étude de cas est disponible en français. Este estudio de caso está disponible en español.

A key strategy for fighting tuberculosis is treatment of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI), especially in countries like Canada where an important proportion of active TB cases are a result of LTBI reactivation.

According to the Canadian Tuberculosis Standards 7th Edition, LTBI screening should be considered for groups at high risk for reactivation including immigrants and refugees from countries with high TB incidence, Aboriginal peoples, and people with medical risk factors that increase TB reactivation such as HIV infection (1,2). However, since sustained LTBI treatment adherence is challenging, it is invaluable to learn about any approach that contributes to improved LTBI management outcomes.

Dione Benjumea, a physician and PhD student at NCCID, developed a report on the factors that have contributed to BridgeCare Clinic’s LTBI success. Here, we share the highlights of their inclusive, integrated, patient-centred public health approach.

Origins: The LTBI Program at BridgeCare Clinic

There are discussions among TB experts about the best way to deliver care, with research evidence that supports integrated primary care models in some settings, and other study findings that demonstrate effectiveness when delivery is primarily through specialists. In the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority (WRHA), non-complex LTBI assessment and management is distributed among primary care TB specialty health clinics. This reflects a recent movement towards a decentralized, intersectoral and integrated model of care for people living with LTBI in Winnipeg.

BridgeCare Clinic opened in November 2010 with the intent of providing comprehensive primary care for government-assisted refugees during their first year in Winnipeg (3). Approximately 500 refugee clients come each year to the BridgeCare Clinic. They most often come from countries in the Middle East, the Horn of Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. Government-assisted refugees are referred to BridgeCare Clinic by two settlement agencies, Welcome Place and Accueil Francophone, which both provide transition housing and other services for refugees in Winnipeg. Under the new direction of the WRHA’s Integrated Tuberculosis Services (ITBS) program, LTBI screening and treatment services were introduced at BridgeCare Clinic shortly after opening.

Adults are eligible for LTBI screening if they have come from a TB endemic country, defined as a country with more than 30 cases of TB per 100,000 people every year. Refugee children are also seen at BridgeCare Clinic, but are not screened for LTBI. Based on the medical histories provided by the clients, women and men between 18 and 49 years of age may be eligible for LTBI screening as a part of their intake process (See Box).

End TB Strategy

The WHO End TB Strategy calls for integrated, patient-centred care and prevention. This means that the needs and expectations of patients must be systematically assessed and addressed. It requires that all patients receive educational,

emotional and economic support to empower them to complete the diagnostic process and full course of treatment.

In 2013 BridgeCare Clinic began a pilot project to offer adults free screening for LTBI with a tuberculin skin test (TST), followed by a whole blood test (interferon-gamma release assay, or IGRA) if the TST was positive. After finding significant challenges, with the use of TST requiring up to 4 visits to the clinic, BridgeCare Clinic switched from the combined TST/IGRA approach to the sole use of IGRA testing in 2014. IGRA was provided at no cost for clients through an in-kind contribution from Cadham Provincial Laboratory where the tests were performed.

From Tip-to-Tail: LTBI Screening and Treatment Services

Basic medical screening is offered to refugees within two weeks of their arrival to Canada. Upon receiving a referral from the settlement agencies, a primary care nurse will schedule the first appointment and reserve a language interpreter if needed (interpreter services are funded by the WRHA and are available in person and by phone). The nurse may ask the interpreter to call the client and confirm the appointment. During the first appointment, the client will meet a primary care nurse and an outreach worker. Initial physical information (height, weight, visual, dental and pregnancy screening) is recorded and blood samples are drawn for a complete blood count, liver enzymes (ALT), and some other infectious diseases screening. The outreach worker explains some of the provisions of the Canadian health care system, including immunization schedules and other services provided. The outreach work will also ask about the client’s family situation and other languages spoken.

A follow-up visit with a physician or nurse practitioner is scheduled a few weeks after the first appointment. This second visit includes a complete physical examination and review of the blood test results. If the IGRA test is positive, the physician or nurse practitioner will inform the client of the result and discuss LTBI. A chest X-ray (performed off-site) is ordered to rule out active TB. If the chest X-ray is normal, and the patient is eligible for LTBI treatment, isoniazid (INH) treatment for nine months is offered. (If active TB is detected, patients are referred to a respirologist at Winnipeg’s Health Sciences Centre tertiary hospital.) If there is any evidence of liver dysfunction, four months’ treatment with rifampin (RIF) is discussed.

Education is a very important part of the process for LTBI management at BridgeCare Clinic. When medications are started, the primary care nurse explains to the client the difference between active and latent TB, the natural history of LTBI, management of LTBI including medications and potential side effects, the need for contraception to prevent pregnancies, adherence, and the importance of minimizing the use of other potential hepatotoxins such as alcohol and acetaminophen.

The first month of medication is provided to the patient for free from the stock at BridgeCare Clinic. Clients are followed monthly, with visits scheduled by the nurse and recorded on a card that the client keeps. Clients also receive pamphlets in their own language with information regarding LTBI. At the end of the 12-month period when clients are referred to another clinic for ongoing primary care, the LTBI screening results are also transferred. If an individual declines treatment, the primary care nurse will provide her or him with information about the signs and symptoms of active TB to watch for. Clients will also receive a letter from the primary care nurse with the same information and their test results will be sent to their home.

ELIGIBILITY FOR LTBI TREATMENT

To be eligible for LTBI treatment, women and men must be:

- Not pregnant

- Not on a medication that is incompatible with INH

- Not having a medical condition that would contraindicate taking INH (i.e. chronic hepatitis B, elevation of baseline ALT)

- Not having a condition that predicts non-adherence (e.g., untreated mental health disorder, memory issues, etc.)

Adhering to TB treatment is challenging. If clients wish to discontinue treatment, the primary care nurse counsels them on the importance of adherence and asks the patients about what is making adherence difficult for them. Where possible the challenges are mitigated to make it easier for clients to continue treatment. If clients discontinue treatment, they receive documentation regarding their LTBI diagnosis and treatment, as well as information on the signs and symptoms of active TB. When clients miss a follow-up appointment, the clinic staff calls them to set up a new appointment, and if someone moves to another province, BridgeCare Clinic notifies Manitoba Health, Communicable Disease Control, and it will notify the RHA in the client’s new province in order for them to resume LTBI treatment.

A client who successfully finishes the treatment receives a letter recording the completed treatment and a letter is also sent to Manitoba Health, Communicable Disease Control.

What are the Outcomes of the Integrated Model at BridgeCare?

According to the Canadian Tuberculosis Standards, a LTBI treatment delivery program should ideally achieve a minimum 80% acceptance of treatment and at least 80% of treatment completion rates (1). According to reviewed studies, most LTBI programs do not achieve these results (4). BridgeCare Clinic, however, has achieved good LTBI treatment acceptance and completion rates—around 80% during 2015 (5). This is consistent with a report from Manitoba Health that found that “key LTBI primary care sites [in Winnipeg]” are at least as good as chest specialists at achieving good treatment outcomes (>75% completion rates) (6).

What Accounts for the Success of the Integrated Model at BridgeCare?

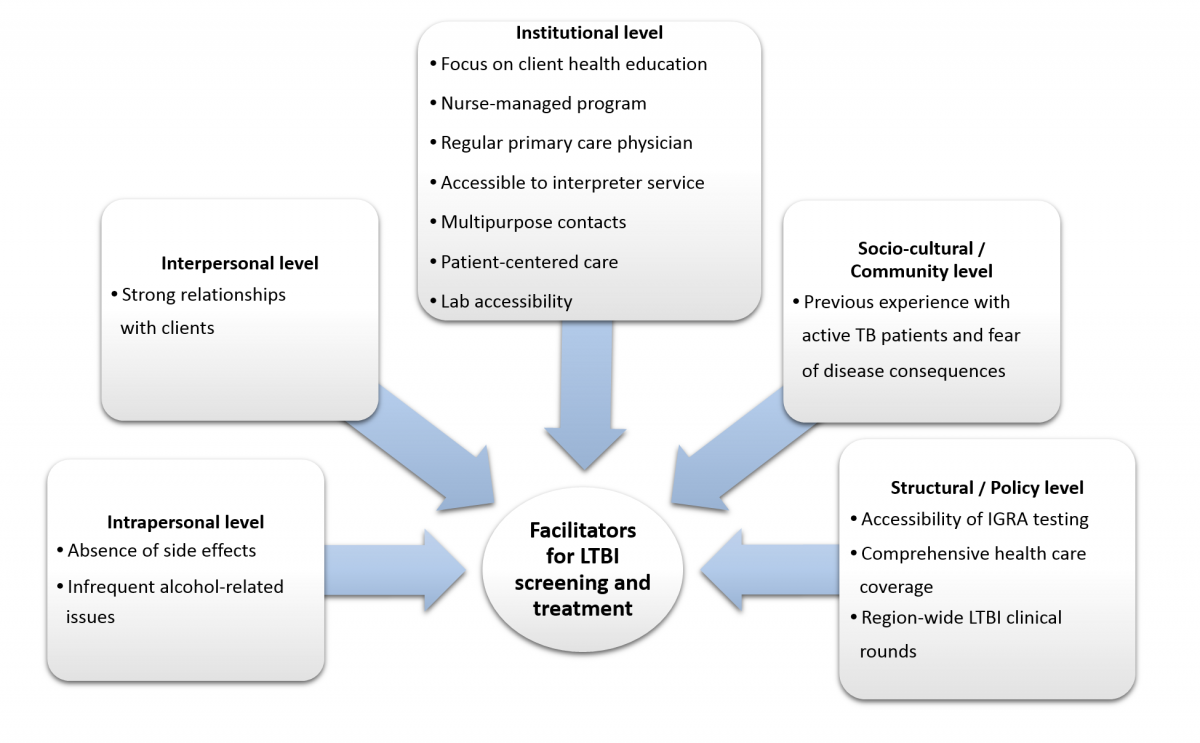

In interviews with the staff at BridgeCare Clinic, a number of features stood out that can be considered to contribute to the high rates of treatment acceptance and completion. These features are outlined here and illustrated in Figure 1.

- The strong relationships that BridgeCare Clinic staff can establish with clients during their integrated care at the clinic helps to promote treatment adherence.

- A patient-centered approach to care that implies taking the clients’ personal needs into account. This includes multipurpose contacts, an accessible interpreter service, active follow-up with clients, and the provision of primary health care to clients’ families, which stimulates family involvement.

- A focus on client education. Health education is provided by both physicians and nurses over numerous visits, and information is reinforced every time.

- The overall program is managed by a primary care nurse, and incorporates nursing care models which emphasize a holistic approach to disease.

- Clients are assigned to a regular primary care provider who is involved in the complete care of clients (as opposed to receiving partial or ephemeral care from multiple health care providers).

- There appears to be a low prevalence of alcohol dependence or issues in the refugee population treated at BridgeCare Clinic, which has been found to increase the likelihood patients will adhere to treatment.

- Side effects are uncommon or mild with first line treatment. Adherence is more likely when patients do not experience nausea as a side effect of the drug INH.

- Laboratory services are accessible and efficient with laboratory sampling for IGRA available in the clinic and at no cost to the client.

- The fact that many refugees have known someone with active TB and its consequences contributes to their willingness to start and complete treatment.

- The comprehensive health care coverage for refugees at BridgeCare Clinic during first year in Canada, and the monthly region-wide clinical rounds specific to LTBI (ITBS rounds) are also considered to contribute to the success of the program at BridgeCare.

“At the beginning of BridgeCare Clinic there was no lab. Then the lab sampling started working a few hours a day, and that was a big challenge to have patients at the right time to take an IGRA test. Now the lab is working more hours a day and that makes everything easier. Before the lab started at BridgeCare Clinic there were many IGRA tests cancelled, and that delayed everything.”

BridgeCare Clinic staff member

“At BridgeCare Clinic, clients receive integrated health care. Health care providers can establish a steady relationship with them, through various visits for multiple purposes including physical examination and vaccine catch up.”

BridgeCare Clinic staff member

Challenges

Most of the critical barriers to providing optimal care at BridgeCare Clinic are related to system-level challenges of limited personnel and other resources. For example, BridgeCare Clinic cannot currently provide LTBI screening for children, and administrative time (making phone calls, for example) can be limited. Clinic staff have identified additional points that make completion of care difficult for LTBI patients:

- It is more difficult for younger clients to understand the need for medication when they are not feeling sick, and they also do not want to miss classes for their LTBI program appointments

- In some cases an adult’s age is unknown, with implications on eligibility criteria for LTBI screening

- Clients can be concerned about the side effects of their medications; and nine months of treatment with isoniazid seems to be long for some patients

- Language is another barrier, with low literacy for some clients and poor communication, despite the interpreter services. In addition, some clients are not familiar with the concept of preventative care for taking the LTBI medications prophylactically

- Unknown medical histories, especially regarding any active TB in the past

- Family planning and pregnancy can sometimes pose challenges as there is some concern of side effects and hepatotoxicity during treatment

- There are still limits to the days and times when blood sampling for IGRA tests can occur, due to the availability of the referral lab and technical issues inherent to the test

- Communication gaps can occur with specialists at tertiary care hospitals over cases referred by Citizenship and Immigration Canada, sometimes resulting in a duplication of services

Finally, the one-year limit on patients’ attendance at BridgeCare Clinic is considered by some staff to create a barrier for men and women receiving care.

Summary and Key Messages

The LTBI program at BridgeCare Clinic is an integrated program managed mainly by a primary care nurse. The BridgeCare Clinic staff consider this significant because every visit a client makes can be multipurpose. The integrated care model includes LTBI screening, assessment and treatment as part of the overall care for clients. Care at BridgeCare Clinic is patient centered, with active follow up. The outreach worker helps families learn to navigate through the health care system. The interpretation service contributes to a more culturally-appropriate approach and improves communications between staff and clients. Patient education is reinforced during appointments in conversations, and with written materials. A significant facilitator to the integrated care has been the ability to offer on-site IGRA tests for LTBI screening from the time refugee women and men arrive at BridgeCare Clinic.

Having enough staff and time with clients are among the resource challenges that can still create barriers for treating LTBI. At the same time, some clients’ lack of health literacy and the concept of preventative care can also impinge on successful treatment, as can concerns about side effects and the long term of isoniazid treatment can be barriers.

Despite these limitations, the integrated LTBI program at BridgeCare Clinic achieves good acceptance and completion rates, due to the Primary Health Care Intersectoral Model implemented by the WRHA. The inclusive and equitable model allows LTBI care be delivered by primary care providers, in a familiar setting.

This case study was developed as part of larger review and assessment of the integrated LTBI program at BridgeCare Clinic. To read the full report, go to nccid.ca/TB.

Related reports

Latent Tuberculosis Infection (LTBI) Management at BridgeCare Clinic: Full Report

Public Health Speaks: Tuberculosis and the social determinants of health, developed by the NCCDH and NCCID

Integrating Equity in Health Care

A health system that is responsive in culturally-appropriate ways to ensure that health services are accessible and acceptable to marginalized populations can play a role in mitigating health inequities. More equitable health outcomes can be achieved by addressing men’s, women’s, girls’ and boys’ needs and experiences related to language, daily transportation, involving family members, and appropriate levels of literacy. Providing care that is truly patient and family centred and connecting clients to community services and other resources can contribute to improve outcomes for all populations.

Find out more at the National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health.

References

- Public Health Agency of Canada, The Lung Association, Canadian Thoracic Society. Canadian Tuberculosis Standards. 7th ed. Canada; 2014. 465 p.

- Pan-Canadian Public Health Network. Guidance for Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Programs in Canada. 2013.

- Winnipeg Regional Health Authority. Health for All. Building Winnipeg’s Health Equity Action Plan. 2013. 62 p.

- Hirsch-Moverman Y, Daftary A, Franks J, Colson PW. Adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis infection: systematic review of studies in the US and Canada. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008 Nov;12(11):1235–54.

- Benjumea-Bedoya D, Bertram Farough A, Plourde P, Lutz J, Hiebert K, Sawatzky C, et al. Latent Tuberculosis Infection (LTBI) Management at BridgeCare Clinic: Full Report. National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases; 2017.

- Manitoba Health, Healthy Living and Seniors. Distribution and Completion of Treated Latent Tuberculosis Infection in Winnipeg. Pre-release Report. 2016.

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Behav. 1988;15(4):351–77.

Production of this document has been made possible through a financial contribution from the Public Health Agency of Canada through funding for the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health (NCCPH).

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the Public Health Agency of Canada. Information contained in the document may be cited provided that the source is mentioned.