Antibiotics are some of the most commonly prescribed pharmaceutical agents in the world, including in Canada. During manufacturing, antibiotics can seep or be discharged into the environment. However, a significant amount can also enter the environment through improper disposal practices (i.e., in sinks, toilets, and household garbage) and natural human excretion. Wastewater treatment systems are not capable of completely removing pharmaceutical residues from entering water supplies and spreading to other environmental features such as soil and surface waters (1–3). There is a range of strategies adopted across the European Union (EU) for collection and disposal of these agents, whilst in Canada approaches are uneven. Where they exist, programs in Canada are estimated to collect only a fraction of unused and expired pharmaceuticals in this country (4).

The accumulation of antibiotics and other antimicrobial agents in the environment can contribute to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), the constant evolutionary modification in viruses, bacteria, fungi, and other pathogens against naturally occurring and synthetic antibiotics, antivirals, and antifungals. AMR is considered to be a serious threat to humans worldwide, as drug-resistant strains of common infections, including tuberculosis and malaria, claim the lives of as many as 700,000 people annually (5). Annual deaths due to AMR are estimated to rise to 10 million annually by 2050, leading to an economic loss in excess of US $ 100 trillion (5). AMR is responsible for over 25,000 deaths annually across the EU and represents an annual cost of more than € 1.5 billion due to additional healthcare costs and productivity losses (6). In Canada, about 20,000 hospitalized patients develop a drug-resistant infection each year, incurring about $ 50 million in direct medical costs (7–9). The Ontario Medical Association noted in 2013 that infections are becoming more frequent, deadly, and increasingly more difficult to treat, and that patients are suffering longer with infections that often would have been treated relatively quickly in the previous five to 10 years ago (10). The reported rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections in pediatric hospitals, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) blood-stream infections in adult hospitals, as well as drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae, have all increased between 2014 and 2015 (11), and continue to rise (12). One estimat is that that 1 in 16 patients admitted to Canadian hospitals will acquire a multi-drug resistant infection (7).

Antimicrobial overuse (including over-prescribing) and misuse (i.e., under completion or improper adherence to regimens) are common and are considered to be important factors that contribute to AMR (9). A 2014 commentary published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal highlighted a 2005 systematic review that found that more than one-third of patients did not complete their antibiotics course as prescribed, and unused antibiotics (from past infections) were taken by more than one-quarter of patients for new infections (13). Patients with new bacterial infections who use leftover antibiotics can delay medical assessment, while hindering correct diagnoses and the use of a potentially more suitable antibiotic (13).

In 2017, about 24 million antibiotics were prescribed in Canada, mainly in community settings (14). Canada ranked fourth highest among OECD countries for antibiotic prescriptions filled, following France, New Zealand, and Australia in 2015 (15). Not only are antimicrobials prescribed to Canadians for their own use, but a substantial proportion is also used in veterinary medicine and in agriculture for livestock husbandry. In reports to the 2014 Senate Standing Committee on Social Affairs, Sciences and Technology on Prescription Pharmaceuticals in Canada, witness statements from subject matter experts suggest that as much as 80% of antibiotics are used in animals and livestock (4).

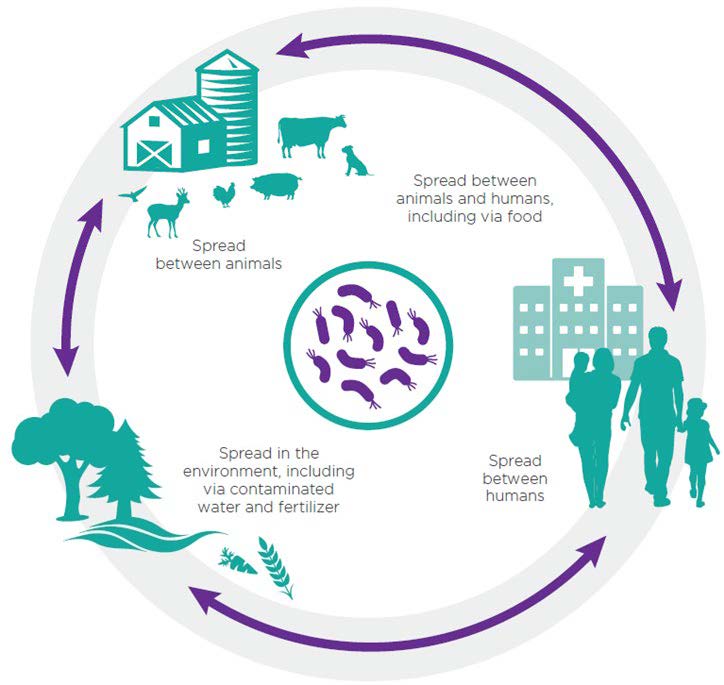

Both excretion of drug residues and run-off into water systems are understood to contribute to the presence of antimicrobials in the environment (Figure 1). Several antimicrobials such as antibiotics, antifungals, and antivirals have been found in water and soil and their presence may play a role in accelerating the development, continuance, and spread of resistant microbes (2,6,16), further reducing the effectiveness of standard first-line antibiotic treatments (16). Almost two decades ago in 2001, the European Commission identified a link between antibiotic waste and the threats of superbugs resulting from antimicrobial resistance (17). The UN Environment report, Frontiers 2017: Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern from UN Environment, has presented evidence linking the discharge of drugs or chemicals into the environment to the growing issue of AMR, identifying this as one of the biggest threats globally (18).

The Pan-Canadian Framework for Action on AMR (9) and the forthcoming pan-Canadian Action Plan are among the latest steps towards more cohesive approaches to plan for and combat the increasing threat of AMR in Canada. Various discussions and documents call for AMR surveillance programs to integrate, or at least consider, both human and animal health sectors. There is also agreement on the need to work towards a better understanding of the contribution of environmental factors to AMR, and opportunities to mitigate the risk of AMR in the environment (9,19).

For over 10 years, the National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCCID) has contributed to knowledge translation and information exchange on antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial stewardship (AMS). In partnership with the National Collaborating Centre for Environment Health (NCCEH), NCCID determined to explore existing evidence on antimicrobial disposal systems in Canada as one aspect of the potential threat of AMR in the environment.

To this end, NCCID conducted this review of evidence to describe the current state of knowledge, policies, guidance, and programs for the disposal of pharmaceuticals, with a focus on antimicrobial drugs in Canada. This review situates the problem of improper pharmaceutical disposal practices in the Canadian context by examining the federal, provincial, and territorial guidelines in Canada. Further, the review describes strategies adopted by two OECD countries to identify promising practices for pharmaceutical disposal, for consideration and adaptation in Canada.

The objectives of this evidence review are to:

- Summarize the evidence available regarding the nature and extent of antimicrobial residues in environmental soil and water in Canada.

- Identify and compare regulatory structures, guidelines, and programs for antimicrobial disposal across the country.

- Explore systems and structures outside of Canada, especially in OECD countries, to identify promising practices for pharmaceutical disposal that could be adapted to the Canadian context.