Points to take away…

In response to the multiple challenges associated with caring for Syrian refugees, public health practitioners in Ontario’s Niagara region developed:

- a one-stop, evidence-based resource for medical students and professionals

- a comprehensive guide to clinical and non-clinical issues

- a list of local social support systems for refugees

- a way to help busy clinicians make informed choices about refugee care promotion

- assistance for medical students with research on disease guidelines and community resources linked to patient care

In December 2015, a group of medical students and residents from McMaster University’s Niagara Regional Campus in St. Catharines, Ontario published Caring for Syrian Refugees: A Guide for Primary Care Providers in Ontario (1). The guide provides a wealth of information about common issues that can arise, including challenges health practitioners might face and ways to meaningfully address them. This case study describes the process of developing the guide, as an example of an evidence-based, promising practice for public health and primary care practitioners working with new immigrants and refugees to Canada. It describes how the guide was started, key challenges medical students and residents encountered in preparing it, and the systematic process adopted in gathering data, and discussing and compiling the information.

Background

Canada has taken a leading role in welcoming refugees from around the world. In November 2015, the federal government released its initial plan to accept 25,000 Syrian refugees and to date, 35,000 Syrian refugees have arrived in 36 different metropolitan areas across the country (2). This sudden, large influx of refugees poses challenges for healthcare providers who may have limited experience with Syrian patients or refugees in general. A comprehensive guide to common healthcare issues facing refugees and potential challenges in provider/ patient encounters can, therefore, help providers prepare for and meet the needs of refugees. Many of the refugees are government-assisted refugees (GARs), while others are privately sponsored and blended visa office referred refugees. Approximately 350 individual communities across Canada (not including Quebec) have welcomed these refugees.¹ These men, women and children have experienced many mental and physical traumas due to conflict, including violence, dislocation, poverty and declining health. Refugees also face many challenges to getting healthcare as a result of language and cultural barriers as well as bureaucratic requirements. Consequently, taking care of these patients requires knowledge of policies as well as healthcare needs.

The guide provides information in the following areas:

| Interim Federal Health Plan (IFHP) coverage | Dental Treatment |

| Procedure adopted by Immigration Medical Examination Board that conducts pre-arrival screening | Infectious and noninfectious diseases commonly reported |

| Primary care considerations & primary care templates | Mental, pediatric and women’s health |

| Language and cultural barriers |

The success of a project is often dependent on a strong, creative and timely idea. In 2015, Dr. Sarah Chaudhry, then a medical resident, proposed the development of a guide to help ease the transition of refugees coming to Canada and to help healthcare providers care for and support refugee patients. Dr. Karl Stobbe, the Associate Dean of McMaster University’s Niagara campus, shared the idea with the area’s wider medical community. Faced with an impending influx of Syrian refugees, McMaster University medical graduates and current students, as well as regional physicians and community members, responded enthusiastically. Researchers, writers, and editors volunteered their time and skills in the development of the guide, independent of either outside funding or partnerships.

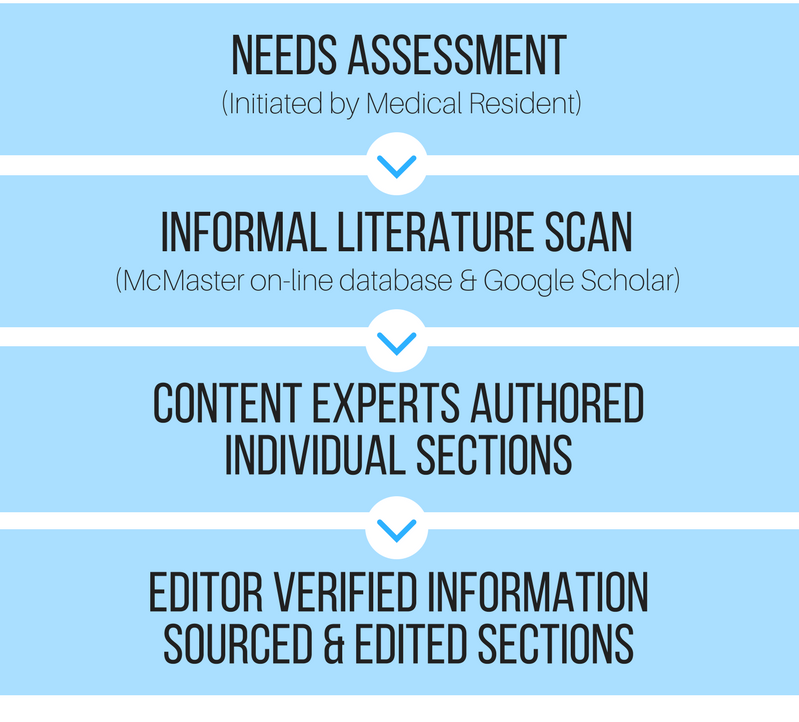

Figure 1. Snapshot of Niagara Report Generation Process

During an initial needs assessment, physicians described multiple challenges associated with caring for Syrian refugees. It became clear that a comprehensive guide, including clinical and non-clinical issues as well as a list of local social support systems for refugees, would be a valuable asset. It would help clinicians, who are often pressed for time, to make informed choices about providing care to Syrian refugees. It would also assist medical students, who frequently spend a great deal of time researching individual guidelines for particular diseases and specific community resources linked with those for patient care. In other words, the guide would serve as a one stop, evidence-based resource for medical students and professionals in the region.

The starting point in the guide’s development was an informal literature scan to look for gaps. The search strategy included a thorough scan of McMaster University’s on-line database and Google Scholar search. Statistics were reported from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) websites such as UNHCR, UNICEF, and World Vision, to name a few. Individual content experts performed independent research in their areas of expertise and then authored relevant sections. A team of three edited the text and double-checked all resources.

With Canada poised to welcome thousands of Syrian refugees, time was of the essence: it was a challenge to quickly assemble a team of medical professionals with different areas of expertise and experience with refugees from different locations. Amazingly, the guide was written, edited and produced in a little more than six weeks, completed just before the first group of Syrian refugees arrived. The timeliness, speed, and success of the project clearly demonstrate the team’s level of commitment and motivation.

Elements of success

With many resources on the care of refugees freely available—including the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ) clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees and guiding principles by the Canadian Pediatric Society (CPS)—there was still a need for information about community resources. A distinct aspect of the guide is that, along with comprehensive clinical and nonclinical guidelines, it listed refugee-specific, regional social system supports in plain, user-friendly language. A handy set of common medical phrases in Arabic also addressed language barriers between seekers and providers of care.

The enthusiastic response of the medical community demonstrates the need for this and other guides to the diverse aspects of healthcare. As an example of successful collaboration among service providers and community, the fact it was overseen by a small group of people with a overall vision of the work was crucial. Other jurisdictions considering the development of such a resource should keep in mind that a project of this type and size requires a substantial investment of volunteer editing time.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this case study would have not been possible without kind contributions from medical staff in Niagara Region, especially:

- Dr. Karl Stobbe, Regional Assistant Dean, Niagara Regional Campus, McMaster University, St. Catharines, ON

- Dr. Sarah Choudhry, Resident, Welland McMaster Family Health Team, Welland, ON

endnotes

1. Information about refugees in Quebec is available on the Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada website. (2)

References

- Niagara Folk Arts Multicultural Centre (2015). Caring for Syrian refugees: A guide for primary care providers in Ontario (1st ed.).

- Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada. (9 February 2017). Welcome Refugees: Key Figures. Retrieved from http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/ refugees/welcome/milestones.asp

Production of this document has been made possible through a financial contribution from the Public Health Agency of Canada through funding for the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health (NCCPH).

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the Public Health Agency of Canada. Information contained in the document may be cited provided that the source is mentioned.