Background & Introduction

The global refugee crisis since the early 2010s has gained substantial attention from the media, academia, and the public. Research regarding preferred destination countries’ public health response to the refugee crisis has been well documented and described both in grey literature and in academic journals.1 Amidst such issues, a recent phenomenon in Canada has caught much attention of the media and the public. The number of asylum seekers crossing the U.S.–Canada border has increased since the U.S. elections in November, 2016. In January, 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump signed an executive order that closed the door to visitors from seven Muslim-majority countries: Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen.2 The executive order also included provisions that suspends Syrian refugees indefinitely, and decreases the number of new refugees allowed in fiscal year 2017 from 110,000 to 50,000.3 The travel ban, fear of deportation, and prospect of life in a country perceived by many as having more liberal policies toward asylum seekers, has resulted in a rising number of people crossing the border to Canada through remote fields and forests despite the risk of frostbites in the winter cold.2 Just in the first six months of 2017, 4,345 asylum seekers crossed the U.S.–Canada border, and the vast majority, 3,350, arrived in Quebec, followed by 646 in Manitoba and 332 in B.C.4

Asylum seekers are entering Canada through dangerous routes due to a loophole in the agreement between the United States and Canada known as the Safe Third Country Agreement. The agreement, signed in 2004, prohibits refugees residing in one country from seeking asylum in the other.2 However, the agreement does not cover those who cross the border unofficially in remote areas far from official border crossings. Therefore, asylum seekers are choosing to become “irregular migrants” by crossing the border in remote fields to gain entry into Canada.2

Although the typical health care needs of asylum seekers is well documented,1 the uniqueness of the recent asylum seeker phenomenon calls for a different perspective for the following reasons: first, the health status of the particular population of asylum seekers who have spent various amounts of time in the U.S. is largely unknown. These asylum seekers are unique in that they likely received some form of health assessment and screening before or upon entry into the United States. However, there have been no published data or official statements on the asylum seekers’ health status, whether Canadian health care authorities have access to their health records, and how continuity of care was managed before entry into Canada. In addition, asylum seekers undergo numerous agencies at the federal, provincial, and non-governmental levels upon entry into Canada.5 These agencies keep information and statistics in different ways, making it difficult to consistently track not only the number of people crossing the border illegally, but also their health status.5

The objective of this report is to review the international literature, with emphasis on members of the European Union, regarding asylum seeker health status, access to health care, and barriers to access. In addition, it will identify current gaps in the knowledge and their implications in the Canadian context regarding the asylum seekers who have recently entered Canada, and ultimately aid in establishing appropriate services for this population.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

Literature was searched by using the following databases: PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, and ProQuest. Search terms included: Asylum seeker, refugee claimant and healthcare policy, health status, Europe, Canada, access to health care, barriers to health care. For official publications from European regional health authorities, the World Health Organization European Region and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control websites were searched. Relevant grey literature was also found by internet-based search of newspaper articles on Google, CBC, Reuters, and The Globe and Mail. Furthermore, the reference sections of key review articles were hand searched for additional articles that were relevant to the search.

Study Selection

Studies were assessed for inclusion based on the following criteria: (1) available in full text in English; (2) the primary participants were adult asylum seekers or refugee claimants residing in the host country, (3) published between 2002 and 2017. Both quantitative and qualitative studies were included. Quantitative studies were included for findings on the health status and common diseases or conditions among asylum seekers. Qualitative studies were included for findings on both perceived and actual level of access to healthcare and barriers to access.

Results

Nearly all published papers retrieved were studies from Europe.

Health Status

A comparison of self-reported perception of poor general health status between asylum seekers, refugees, immigrants, and the general non-immigrant population in the Netherlands showed a worse health status among asylum seekers (59.1%) than that of refugees (42%), immigrants (39%), and the general population (18%).6 Although there are variations among study populations, common medical conditions and symptoms reported by asylum seekers included mental health problems, headaches and migraine, dental, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, and respiratory symptoms (Table 1).6-10 Asylum seekers were more likely to report symptoms of PTSD, depression, and anxiety than refugees.11 Risk factors for poor mental health were associated with female sex, older age, experience of trauma, presence of post-migration stressors, and lack of social support.12 Studies that focused on sexual and reproductive health of asylum seekers showed that the incidence of severe acute maternal morbidity is 4.5 times higher in asylum seeking women than that of the general population.13 Asylum seeking women were more likely to have experienced sexual assault,14 had higher rates of unwanted pregnancies and induced abortions (2.5 times higher) than women in the host country.15 Furthermore, asylum seeking women were more likely to report chronic conditions, PTSD, depression, anxiety6 and physical symptoms such as headache, abdominal pain, and backache than men.16 Although studies showed that asylum seekers are at increased risk of mental and sexual health issues, evidence on whether they have higher rates of infectious diseases and chronic conditions than the general population was limited.1

Table 1. List of common medical conditions and symptoms among asylum seekers

- Mental Health Conditions (PTSD, depression, anxiety)

- Headache

- Migraine

- Dental Health Conditions

- Musculoskeletal Symptoms

- Gastrointestinal Symptoms

- Respiratory Illness

Asylum seekers from countries experiencing violent conflict were associated with higher incidence of somatic diseases and increased number of visits to medical facilities.17 Asylum seekers who underwent longer asylum application procedures (>2years) reported significantly lower quality of life, more physical complaints, and higher functional disability than those who had recently arrived in the host country (<6months).8 Furthermore, pre-migration exposure to traumatic events,8 post-migration stressors such as family issues, poor socio-economic living conditions, and socio-religious conflicts were associated with chronic conditions and worse quality of life.8

Access to Healthcare

Most studies that were identified for comparison of different levels of access to healthcare originated from the European region. There was significant variation across Europe in terms of regulations surrounding access to health care for asylum seekers and refugees. Furthermore, a major challenge for assessing asylum seekers’ access to health care was that the literature often uses an umbrella term “migrants” which includes students, economic migrants, asylum seekers, irregular migrants and displaced persons when assessing health care policies for these groups.18 Amidst such challenges, one study specifically compared health care policies targeted for asylum seekers.19 Norredam et al. compared legal restrictions in access to health care for asylum seekers to that of citizens of the host country in 23 European countries.19 In Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Luxemburg, Malta, Spain, and Sweden, there were legal restrictions in access to health care that only entitled asylum seekers to emergency care.19 Of these, only four countries (Germany, Luxembourg, Spain, and Malta) had policies that changed the level of access to health care over time.19 Asylum seekers were eligible for full access to health care 15 months after arrival in Germany.20 In Spain, asylum seekers received the same level of access to health care as host citizens as soon as they are registered at the Town Council, whereas full access to health care was available 3 months after arrival in Luxembourg.19

Barriers to Access

Even if legal restrictions to healthcare access are removed or diminished, asylum seekers are still faced with practical restrictions that act as barriers. In countries where access to free health care is not universal, inability to pay for medical visits was cited as a barrier to seeking care.21 Even when access to free health care was available, other costs associated with transportation, prescription and over-the-counter medications, and other health-related expenses were identified as barriers.22 In addition, asylum seekers found navigating through the healthcare system, which were often very different from that of their countries of origin, very difficult due to lack of awareness on availability and their eligibility for such services.23 Other identified problems were lack of proper dissemination of information regarding available health services upon arrival and inadequate understanding of the primary care and referral system.21 Participants from other studies found that support from friends, family and other agencies were the main source of information regarding health services and that they played an integral part to successful access.21,24

Continuity of care, or lack thereof, was reported as a major determining factor of seeking health care.21,23,25 Continuity of care emerged as a major facilitator of building trust and confidence in health professionals in the host country. In cases where continuity of care and expertise in refugee health were lacking, asylum seekers reported concerns regarding confidentiality and security regarding their health status as there was a perceived threat that their asylum application may be delayed or denied due to their current and previous health conditions.21

Lastly, the language barrier faced by asylum seekers was cited as a major deterrent to health care access in numerous studies.21-24 Lack of professional interpreters who received training in culturally appropriate translation resulted in inappropriate use of friends and family members as informal interpreters. Even in cases where trained interpreters were available, lack of assurance that the asylum seekers’ concerns and needs were accurately being conveyed, and concerns regarding confidentiality were reported as barriers to access.23-25

Recommendation of Regional Health Authorities

In light of what is known about the needs of asylum seekers in the literature, and in response to the unprecedented refugee crisis Europe has experienced in the last ten years, regional health authorities such as the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) have published action plans that provide overall recommendations to its member states.26,27

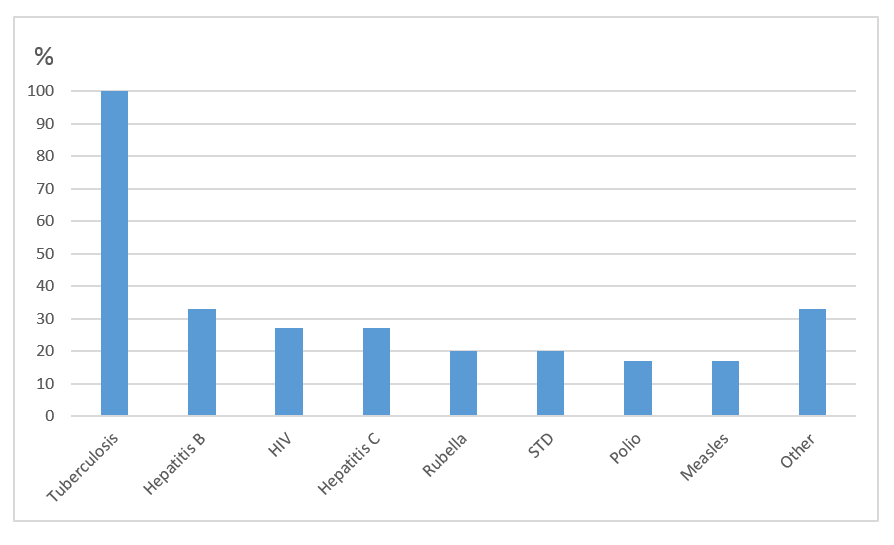

Expert consultations conducted by EDCD yielded recurrent themes such as the need for reception centres for newly arrived migrants where initial health assessments can be carried out immediately upon arrival.27 Adequate resource allocation to these reception centres with primary care and public health services for screening, vaccination, and prompt treatment of ill patients free of charge were cited as the best course of action.27 Experts pointed out the importance of screening for communicable diseases according to the asylum seekers’ country of origin.27 Based on expert reports, only 59% (16/27) of countries in the European Union/ European Economic Area implemented screening for newly arrived migrants.28 National guidelines for screening of newly arrived migrants for at least one disease was available in 56% (15/27) of the countries.28 Within these countries, the most common disease screened for was TB (15/15, 100%), and other diseases screened for included hepatitis B (33%), hepatitis C (27%), HIV (27%), other STDs and vaccine preventable diseases (20%) (Figure 1).28 Furthermore, experts also emphasized the need for adequate housing conditions for newly arrived migrants with proper sanitation standards and minimization of crowded living conditions in order to minimize transmission of communicable diseases.27 Experts also emphasized the importance of a system to track migrants from their initial point of entry to their eventual final destination.27 They emphasized the importance of such a system for continuity of care and for ensuring follow up of vaccinations and booster shots along with treatment supervision and outcome monitoring of communicable diseases such as TB.27

Figure 1. Proportion of diseases screened for in EU countries implementing screening programs (n = 15)

The World Health Organization European Region published a strategy and action plan for refugee and migrant health in September, 2016.26 The plan includes policy recommendations that focus on collaboration of the European region as a whole by establishing a framework for a coordinated response by the international community.26 Another key recommendation found in the plan is strengthening the health information systems for improved data collection on refugee and migrant health. It states that the purpose of such data collection must be explained to refugees, asylum seekers and migrants, along with how it can benefit them in the long run.26 The plan noted that it is imperative that innovative approaches to data collection such as surveys and qualitative methods are conducted while ensuring confidentiality and upholding sound ethical standards.26

Discussion

The majority of literature reviewed in this report was from Europe. This is due to the recent volume and frequency, with massive influx of refugees and asylum seekers, and gained experience in the European region. Between 1990 and 2015, Europe has seen one of the largest growth rates of international migrants.1 According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Europe received 714,300 of the estimated 866,000 total asylum applications in the world in 2014.29 Since Europe has ample experience with providing care for asylum seekers over several decades in large numbers, literature from this region may provide valuable evidence to inform an effective public health response in the Canadian context.

Implications for the Canadian Context

Review of other countries’ responses exposes challenges and gaps in the Canadian public health response to asylum seekers. First, it appears that limited data are being collected on health status and use of public health services of asylum seekers entering Canada as there were no published studies on this topic in the first six months of 2017. There are neither published data, nor any publicly available information on-line on how or if authorities are keeping track of the health care needs, vaccination status, utilization of health care, access to health records, and how continuity of care is being established for this population. Although basic health assessments are conducted in Welcome Centres in towns near the asylum seekers’ first point of entry, there is no national guideline to ensure consistency in collection of data from these assessments. In Manitoba, for example, there is no health screening mechanism in place for asylum seekers entering the province, and no screening is being performed on this population when they seek care directly (J. Lutz. pers. comm. to NCCID).

Normally, refugee claimants who enter Canada are provided with limited, temporary coverage of healthcare benefits under the Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP). The IFHP has received much criticism by health care professionals since the federal government implemented major budget cuts in June, 2012. Budget cuts for IFHP have resulted in reduced coverage in which medications, prosthetics, and elective surgery are not covered. In addition, psychotherapy for victims of torture, rape or other forms of violence is no longer covered, and the rationale for the cuts was that refugees should not be provided with services that are not provided to Canadian citizens, even though most Canadians have not been subjected to torture or traumatizing experiences of war.30 Widespread confusion about who and what is covered has caused great anxiety for people who have already undergone some of the harshest experiences one can endure. Those who are left without coverage live in fear of getting injured, sick, or becoming pregnant while others who may be eligible are not provided with adequate information on services they are entitled to.30 In fact, the Canadian Council for Refugees has stated that patients have been turned away by some clinics, hospitals, and doctors’ offices because of confusion from the increased complexity and in some cases, patients have been asked to pay upfront for their care.30

Despite the apparent flaws, IFHP has been the best hope for refugee claimants’ access to health care. However, there is a significant gap in available services for the recently arrived asylum seekers as funding for public health care does not apply to them. Since the 2012 budget cuts, people waiting for an appointment to make their refugee claim have been left without any coverage for health care.30 Therefore, asylum seekers who need medical attention are forced to go to clinics where the staff voluntarily provide care for this population without compensation (J. Lutz. pers.comm. to NCCID). These clinics are solely reliant on donations and only provide services to the asylum seekers for acute illnesses associated with upper respiratory disease, malaria, prenatal care, and other injuries (J. Lutz. pers.comm. to NCCID).

All of the realities regarding lack of services available to asylum seekers contradict what is widely known in the literature as the best course of action in the long run. Data collection on health status and typical health care needs, health screening, proper follow-up, informing available services, tracking access to health care, comprehensive prenatal care, therapy for mental illnesses, and culturally appropriate interpreters are all imperative services that may result in negative consequences if neglected. Therefore, policy changes that result in establishment of appropriate services as suggested by findings from the literature will prove to be essential. However, many challenges lie ahead. One major challenge in the future may be the public’s resistance to policy change, as survey results showed that more Canadians want to deport the asylum seekers back to the U.S. (48%) than let them remain in Canada and seek refugee status (36%).31 Policy changes involving health care resource allocation for asylum seekers at the expense of the general population may face difficulties due to less than welcoming view toward the asylum seekers by the Canadian public.

Limitations

Several limitations regarding the quality of studies reviewed need to be addressed. Except for a few studies that used random sampling of asylum seekers in the community, most studies included in this review recruited participants through convenience sampling of those who visited health service centres. This may have resulted in overrepresentation of certain health needs and barriers to access, and underrepresentation of conditions for which asylum seekers are less likely to seek care for. Furthermore, the high proportion of cross-sectional study design and possible issues arising from poor translation of survey material along with uncertain reliability of interpreters in some studies are other notable limitations.

Asylum seekers who entered Canada in fear of emerging policies such as the travel ban represent a unique demographic for which further research is required. Most have spent extended periods of time in the United States. The health impact that may have resulted on the asylum seekers during their stay in the U.S. is largely unknown. The initial route of entry into the United States, health screening results and parameters if conducted, number and purpose of health care visits, and if public funding for health care were provided are all vital information that need to be acquired if an effective public health response is to be established. In addition, the differences in country of origin of asylum seekers entering Canada and Europe may be another limitation of the studies reviewed. Over the first six months of 2017 in Manitoba, the top three countries of origin of asylum seekers were Djibouti (34%), Somalia (30%), and Ghana (10%),5 while the top three in Europe were Syria (20.6%), Iraq (9.3%), and Afghanistan (8.2%) in 2014.29

Lastly, limitations and challenges arose from inconsistent use of terminology in the literature. Restricting the search terms to asylum seekers may have excluded some studies that use some terms that are commonly used interchangeably (refugee, refugee claimant, migrant, etc.). Such inconsistent and incorrect use of legal terms related to asylum seekers leads to unnecessary confusion in the literature which may act as barriers to further research on the subject.

References

1. World Health Organisation. Public health aspects of migrant health: a review of the evidence on health status for refugees and aslum seekers in the European Region. WHO Eur. 2015:1-29. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/289246/WHO-HEN-Report-A5-2-Refugees_FINAL.pdf?ua=1.

2. Asylum seekers from the U.S.: A guide to the saga so far, and what Canadians think of it – The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/asylum-seekers-from-the-us/article34095595/. Accessed July 2, 2017.

3. Judges temporarily block part of Trump’s immigration order, WH stands by it – CNNPolitics.com.http://www.cnn.com/2017/01/28/politics/2-iraqis-file-lawsuit-after-being-detained-in-ny-due-to-travel-ban. Accessed August 2, 2017.

4. Illegal border crossings by asylum seekers decline in Manitoba but spike in Quebec – Politics – CBC News. http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/illegal-border-crossings-canada-june-1.4216566. Accessed July 27, 2017.

5. Update on number of asylum seekers only tells part of the story – Manitoba – CBC News. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/analysis-asylum-seeker-numbers-1.4078006. Accessed July 2, 2017.

6. Gerritsen AAM, Bramsen I, Devillé W, van Willigen LHM, Hovens JE, van der Ploeg HM. Physical and mental health of Afghan, Iranian and Somali asylum seekers and refugees living in the Netherlands. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(1):18-26. doi:10.1007/s00127-005-0003-5.

7. Blackwell D, Holden K, Tregoning D. An interim report of health needs assessment of asylum seekers in Sunderland and North Tyneside. Public Health. 2002;116(4):221-226. doi:10.1038/sj.ph.1900852.

8. Laban CJ, Komproe IH, Gernaat HBPE, Jong JTVM. The impact of a long asylum procedure on quality of life, disability and physical health in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(7):507-515. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0333-1.

9. Redman EA, Reay HJ, Jones L, Roberts RJ. Self-reported health problems of asylum seekers and their understanding of the national health service: A pilot study. Public Health. 2011;125(3):142-144. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2010.10.002.

10. Toar M, O’Brien KK, Fahey T. Comparison of self-reported health & healthcare utilisation between asylum seekers and refugees: an observational study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):214. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-214.

11. Toar M, O’Brien KK, Fahey T. Comparison of self-reported health & healthcare utilisation between asylum seekers and refugees: an observational study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):214. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-214.

12. Gerritsen AAM, Bramsen I, Devillé W, Van Willigen LHM, Hovens JE, Van Der Ploeg HM. Use of health care services by Afghan, Iranian, and Somali refugees and asylum seekers living in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(4):394-399. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckl046.

13. Van Hanegem N, Miltenburg AS, Zwart JJ, Bloemenkamp KWM, Van Roosmalen J. Severe acute maternal morbidity in asylum seekers: A two-year nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(9):1010-1016. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01140.x.

14. Rogstad K, Dale H. What are the needs of asylum seekers attending an STI clinic and are they significantly different from those of British patients? Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(8):515-518. doi:10.1258/0956462041558230.

15. Kurth E, Jaeger FN, Zemp E, Tschudin S, Bischoff A. Reproductive health care for asylum-seeking women – a challenge for health professionals. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):659. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-659.

16. Bischoff A, Bovier PA, Isah R, Françoise G, Ariel E, Louis L. Language barriers between nurses and asylum seekers: Their impact on symptom reporting and referral. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(3):503-512. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00376-3.

17. Bischoff A, Denhaerynck K, Schneider M, Battegay E. The cost of war and the cost of health care – An epidemiological study of asylum seekers. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141(OCTOBER):13-16. doi:10.4414/smw.2011.13252.

18. Mladovsky P. A framework for analysing migrant health policies in Europe. Health Policy (New York). 2009;93(1):55-63. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.05.015.

19. Norredam M, Mygind A, Krasnik A. Access to health care for asylum seekers in the European Union – A comparative study of country policies. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(3):285-289. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cki191.

20. Bozorgmehr K, Razum O. Effect of restricting access to health care on health expenditures among asylum-seekers and refugees: A quasi-experimental study in Germany, 1994-2013. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):1994-2013. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131483.

21. Asgary R, Segar N. Barriers to health care access among refugee asylum seekers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(2):506-522. doi:10.1353/hpu.2011.0047.

22. Spike EA, Smith MM, Harris MF. Access to primary health care services by community-based asylum seekers. Med J Aust. 2011;195(4):188-191.

23. O’Donnell CA, Higgins M, Chauhan R, Mullen K. “They think we’re OK and we know we’re not”. A qualitative study of asylum seekers’ access, knowledge and views to health care in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:75. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-7-75.

24. Bhatia R, Wallace P. Experiences of refugees and asylum seekers in general practice: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8(1):48. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-8-48.

25. O’Donnell CA, Higgins M, Chauhan R, Mullen K. Asylum seekers’ expectations of and trust in general practice: A qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(557):870-876. doi:10.3399/bjgp08X376104.

26. World Health Organization. Strategy and action plan for refugee and migrant health in the WHO European Region. 2016;(September):12-15.

27. ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control). Expert Opinion on the public health needs of irregular migrants , refugees or asylum seekers across the EU ’ s southern and south-eastern borders. 2015:20. doi:10.2900/58156.

28. Karki T, Napoli C, Riccardo F, et al. Screening for Infectious Diseases among Newly Arrived Migrants in EU/EEA Countries-Varying Practices but Consensus on the Utility of Screening. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(10):11004-11014. doi:10.3390/ijerph111011004.

29. UNHCR. Asylum Trends 2014. Levels and Trends in Industrialized Countries. United Nations High Comm Refug. 2015:28. http://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/551128679/asylum-levels-trends-industrialized-countries-2014.html.

30. Canadian Council for Refugees. Refugee Health Care : Impacts of Recent Cuts.; 2013. http://ccrweb.ca/sites/ccrweb.ca/files/ifhreporten.pdf.

31. Nickel BR, Ljunggren D. Exclusive : Almost half of Canadians want illegal border crossers deported – Reuters poll.http://ca.reuters.com/article/topNews/idCAKBN16R0SK-OCATP. Published 2017.

Production of this document has been made possible through a financial contribution from the Public Health Agency of Canada through funding for the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health (NCCPH).

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the Public Health Agency of Canada. Information contained in the document may be cited provided that the source is mentioned.