November 15, 2022

NCCID Disease Debriefs provide Canadian public health practitioners and clinicians with up-to-date reviews of essential information on prominent infectious diseases for Canadian public health practice. While not a formal literature review, information is gathered from key sources including the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO) and peer-reviewed literature.

This disease debrief was prepared by Shyama Nanayakkara. Questions, comments, and suggestions regarding this disease brief are most welcome and can be sent to nccid@manitoba.ca.

What are Disease Debriefs? To find out more about how information is collected, see our page dedicated to the Disease Debriefs.

Questions Addressed in this debrief:

- What are important characteristics of Respiratory Syncytial Virus?

- What is happening with current outbreaks of Respiratory Syncytial Virus infection?

- What is the current risk for Canadians from Respiratory Syncytial Virus infection?

- What measures should be taken for a suspected Respiratory Syncytial Virus infection case or contact?

What are important characteristics of Respiratory Syncytial Virus?

Causes

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) is a very common virus that causes infections of the respiratory tract. It is an enveloped, negative sense, single-stranded RNA virus which belongs to the Orthopneumovirus genus in the Paramyxoviridae family. Virus particles are enveloped and pleomorphic, occurring as irregular spherical particles that are 100 to 350 nm in diameter, and as long filamentous fibres that are 60 to 200 nm in diameter and 10 mm in length. Two subtypes of RSV have been identified: RSV/A and RSV/B. Subtype A is more prevalent than subtype B.

RSV infects human airway cells, infecting both the upper and lower airways. Severe disease clinically manifests as influenza-like illnesses and lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI), with bronchiolitis being the most common severe presentation in young children.

Signs and Symptoms

RSV inflection incubation period ranges from 2-8 days.

People infected with RSV usually show symptoms within 4-6 days after getting infected. It usually causes mild, cold-like symptoms such as: runny nose (rhinorrhea), coughing, sneezing, fever, wheezing, and/or decrease in appetite. In babies, symptoms include irritability, decreased activity, and breathing difficulties. RSV can be life-threatening, especially for infants and older adults. It is the most common cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia – more severe infections of RSV – in children less than 1 year of age. Primary infection with RSV is generally exhibited as lower respiratory tract disease, pneumonia, bronchiolitis, tracheobronchitis, or upper respiratory tract illness.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Other than monitoring for symptoms, most used RSV are diagnosed clinically. Laboratory diagnosing RSV, includes virus cultures, serology, immunofluorescence and/or antigen detection, and nucleic acid-based tests. The first two techniques are rarely used. Laboratory tests commonly used are real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) which is the most sensitive and antigen testing (only sensitive in children and not sensitive for older children and adults because they may have lower viral loads in their respiratory specimens). This is because many RSV symptoms are non-specific and overlap with other viral respiratory and bacterial infections.

Treatment

Most RSV infections go away on their own in 1-2 weeks. There is no specific treatment for RSV infections, though researchers are working to develop vaccines and antivirals.

One can take steps to relieve symptoms associated with RSV infections like managing the fever and pain with over-the-counter fever reducers and pain relievers, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen (don’t give aspirin to children). Drink fluids to prevent dehydration.

Will need to be hospitalized:

- If older adults and infants younger than 6 months are having trouble breathing or are dehydrated

- If require additional oxygen or intubation with mechanical ventilation

A drug called palivizumab is available to prevent severe RSV illness in certain infants and children who are at high risk for severe disease. The drug can help prevent serious RSV disease, but it cannot cure or treat children already suffering from serious RSV disease, and it cannot prevent infection with RSV. It is given in monthly intramuscular injections during peak RSV season (late fall to spring).

Severity and Complications

RSV infections can range from mild upper respiratory tract (URT) infections to severe lower respiratory tract (LRT) infections. RSV infections usually begin with upper respiratory tract disease which has the tendency to progress to lower respiratory tract disease in ~50% cases. Most RSV infections will go away on their own in 1-2 weeks.

While RSV can cause respiratory tract infections in people of all ages and is among the most common childhood infections, its presentation and severity often vary between age groups and immune status. Infants, older adults (+65), and immunocompromised individuals are more susceptible to developing severe disease such as bronchiolitis and pneumonia where in both cases, the infection has spread from URT to LRT. In some cases, otitis media may occur (more common in babies and young children).

RSV can also make chronic health problems like asthma or heart and lung disease worse like a person may experience asthma attacks as a result of RSV infection.

Reinfection is common throughout life.

- PHAC – RSV Pathogen Safety Data Sheet

- PHAC – RSV

- CDC – RSV High Risk

- CDC – RSV in Infants and Young Children

- CDC – RSV in Elderly and Chronic Health Conditions

Epidemology

General

RSV is endemic worldwide and cases are reported throughout the year. The age distribution of RSV disease burden is bimodal, with the greatest impact felt in the first 2 years of life and in older adults. Annually, RSV disease is estimated to cause 3.4 million hospitalizations and 100,000 deaths globally. Infection rates typically peak during cold winter months (late fall to spring).

Factors that may predispose to RSV infection include crowding (schools and day care centres), exposure to tobacco and smoke, low socioeconomic status, and family history of atopy and asthma.

- PHAC – RSV

- PHAC – RSV Pathogen Safety Data Sheet

- CDC – RSV Transmission

- PHAC – RSV Pathogen Safety Data Sheet

Incubation Period

RSV inflection incubation period ranges from 2-8 days

Reservoir and Transmission

Humans are the reservoir for RSV. It is transmitted through direct contact with infectious secretions via fomites and large-particle aerosols. For example, RSV can spread when an infected person coughs or sneezes and the virus droplets enters the body through the eyes, nose, or mouth as it easily spreads through the air on infected respiratory droplets.

The virus can also be transmitted from a person touching an infected surface like a doorknob and then touching their face before washing their hands. RSV can survive for many hours on hard surfaces (table) as compared to soft surfaces (hands).

RSV is also a major cause of nosocomial infections.

An infected person is most contagious during the first week or so after infection. However, in infants and those with weakened immunity, the virus may continue to spread even after symptoms go away, for up to 4 weeks. Person-to-person transmission is unlikely, since significant and prolonged contact is required with infected individuals. Children are known to shed the virus for long periods.

People of any age can get another RSV infection, but infections later in life are generally less severe.

Prevention and Control

If you have cold-like symptoms, you should:

- Cover your coughs and sneezes with a tissue or your upper shirt sleeve, not your hands

- Wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds

- Avoid close contact, such as kissing, shaking hands, and sharing cups and eating utensils, with others

- Clean frequently touched surfaces such as doorknobs and mobile devices

Avoid interacting with children at high risk for severe RSV disease, including premature infants, children younger than 2 years of age with chronic lung or heart conditions, and children with weakened immune systems.

Vaccination

Researchers are working to develop RSV vaccines. Phase 3 clinical trials for RSV vaccine for pregnant women, infants, children and older adults are under way. This includes four active immunizing agents (live-attenuated, particle-based, subunit-based and vector-based vaccines) and one new passive immunizing agent (monoclonal antibody).

A prophylactic drug called palivizumab is available to prevent severe RSV illness in certain infants and children who are at high risk for severe disease. Through the RSV Prophylaxis for High-Risk Infants Program (RSV program), the Ministry of Health (MOH) covers the full cost of the drug. The drug can help prevent serious RSV disease, but it cannot help cure or treat children already suffering from serious RSV disease, and it cannot prevent infection with RSV. It is given in monthly intramuscular injections during peak RSV season (late fall to spring).

What is happening with current outbreak of Respiratory Syncytial Virus infection?

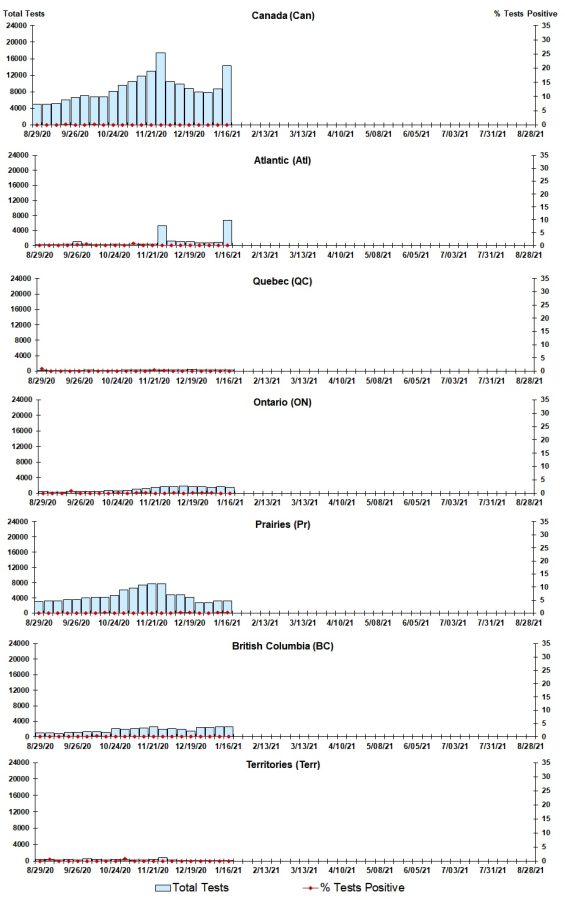

Overall, the number of positive RSV cases in Canada since august 2020 is low. This is an improvement from 2018-2019 when 17.7% of the cases were RSV positive in Canada.

RSV tests (%) in Canada by region by surveillance week 44 – ending November 5, 2022

What is the current risk for Canadians from Respiratory Syncytial Virus infection?

RSV is a seasonal infection that occurs worldwide. The active season for RSV is generally November to April. In healthy adults and older children, RSV commonly mimics the symptoms of a common cold. Most children are infected at least once by age 2 and continue to be reinfected throughout life

However, certain populations that are at high risk for severe RSV infections include:

- Infants, especially premature infants or babies who are 6 months or younger

- Children who have heart disease that’s present from birth (congenital heart disease) or chronic lung disease

- Children or adults with weakened immune systems from diseases such as cancer or treatment such as chemotherapy

- Children who have neuromuscular disorders, such as muscular dystrophy

- Adults with heart disease or lung disease

- Elderly, especially those age 65 and older

- PHAC – RSV Pathogen Safety Data Sheet

- PHAC – RSV

- CDC – RSV High Risk

- CDC – RSV in Infants and Young Children

- CDC – RSV in Elderly and Chronic Health Conditions

Travel Recommendations

RSV is common worldwide, but no additional precautions are needed when traveling. RSV generally peaks between November and April so washing your hands often and avoid touching eyes, nose, and mouth without washing your hands is a good preventative strategy.

What measures should be taken for a suspected Respiratory Syncytial Virus infection case or contact?

Case and Contact Management

Most RSV infections go away on their own in 1-2 weeks. Consult with your healthcare provider and give all medicines as instructed. Get plenty of rest and stay hydrated by drinking plenty of fluids. Any breathing difficulties in an infant should be considered an emergency, so seek immediate help.

Case Definitions

The WHO uses an “extended SARI” case definition for hospital-based surveillance for severe RSV infections and “ARI” case definition for community-based surveillance for RSV infection. WHO has also launched phase 2 global RSV surveillance.

These case definitions are strictly for the purpose of case identification, reporting, and estimating disease burden.

Identifying and Reporting

According to Public Health Ontario, test results are reported to the ordering health care provider that has been indicated on the requisition form. Outbreak-related positive results are reported to the Medical Officer of Health as per the Health Protection and Promotion Act.

Infection Control and Prevention

There is currently no vaccine to prevent RSV infection. RSV infection is often resolved on its own. For babies and children who are at high risk of developing severe RSV, preventive medication is available and should be given as instructed by their healthcare provider. Additionally, typical cold precautions during peak RSV season (late fall to spring) should be taken like:

- Washing your hands often

- Do not touch your eyes, nose, or mouth without washing your hands first (Soap and water and disinfectants easily inactivate the virus)

- Avoid exposure to sick persons if possible