Are you looking for the PHAC guidance document for practitioners?

NCCID Disease Debriefs provide Canadian public health practitioners and clinicians with essential information on prominent infectious diseases for Canadian public health practice. While not a formal literature review, information is gathered from key sources including the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the World Health Organization (WHO), and peer reviewed literature.

This Disease Debrief was prepared by Signy Baragar.

Updated: December 3, 2025

What are Disease Debriefs? To find out more about how information is collected, see our page dedicated to the Disease Debriefs.

What are important characteristics of Mumps?

CAUSE

Mumps infection is caused by the mumps virus, an enveloped, negative-sense, single stranded RNA virus which belongs to the Rubulavirus genus in the Paramyxoviridae family.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Anyone who is not vaccinated against mumps, or has not previously had mumps, can be infected. Most people who are infected with mumps are asymptomatic or have very mild symptoms, however, they can still transmit the virus to others. If symptoms are present, the most common characteristic is painful swelling of the salivary gland(s) on one or both sides of the cheek or neck. Other symptoms can include fever; headache; malaise; dry mouth; tiredness; muscle aches; trouble talking; chewing or swallowing; and/or a loss of appetite. Mumps infection can also sometimes present mild symptoms similar to a cold. Most people with mumps recover within two weeks.

People who are unvaccinated against mumps are more likely to develop symptoms, such as fever and swollen salivary glands, and complications linked with infection than those who are vaccinated.

SEVERITY AND COMPLICATIONS

In rare cases, mumps infection can cause severe complications including inflammation of the testicles (orchitis), inflammation of the breasts (mastitis), inflammation of the ovaries (oophoritis), inflammation of the brain (encephalitis), inflammation of the tissue covering the brain and spinal cord (meningitis), temporary hearing loss or permanent deafness.

People who are pregnant are not more at risk of severe infection that those who are not pregnant.

INCUBATION PERIOD

Typically, the mumps incubation period is between 16-18 days, but symptoms may appear between 12-25 days after being exposed to the virus.

RESERVOIR

Humans are the only known host for mumps virus.

TRANSMISSION

Mumps spreads easily and is very contagious with a basic reproductive number (R0) of 10-12. In other words, each infected person will infect 10-12 additional people in an otherwise susceptible population. The virus is spread through contact with respiratory droplets from an infected person, direct contact with the saliva of an infected person, and contact with a contaminated surface. A person infected with mumps is most infectious approximately 2-5 days before showing symptoms, however, they can also be contagious between 7 days before and 9 days after symptom onset.

- PHAC: Mumps virus – Infectious substances pathogen safety data sheet

- PHAC: Mumps for Health Professionals

CASE CONTROL AND MANAGEMENT

As part of the National Immunization Strategy objectives for 2016-2021, in 2025, Canada set vaccination coverage and mumps reduction targets based on international standards and best practices. Consistent with Canada’s commitment to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) disease elimination targets and Global Vaccine Action Plan, Canada’s three targets for mumps prevention and control are:

- Achieve 95% vaccination coverage of one dose of a mumps-containing vaccine (MMR or MMRV) by two years of age

- Between 2015 and 2019, 89% of two-year-old children in Canada had their first dose of the MMR vaccine by their second birthday.

- Achieve 95% vaccination coverage of two doses of a mumps-containing vaccine by seven years of age.

- Between 2015 and 2017, 86% of seven-year-old children in Canada had two doses of the MMR vaccine by their seventh birthday. This coverage dropped to 83% in 2019.

- Maintain an average of less than 100 mumps cases annually in Canada (based on a five-year rolling average).

- In 2019 (range 2018-2019), the five-year rolling average number of annual mumps cases was 734 cases (range 707-734). This is an increase from the five-year rolling average in 2017 (range 2016-2017) which was 565 cases (range 122-565) and 103 cases (range 103-617) in 2015 (range 2011-2015)*

* For Target 3, the data are presented as the five-year rolling average in the reported year, followed by the range of the five-year rolling average over the years specified.

Immunize Canada has developed several resources on mumps immunization for the public and health care professionals.

IDENTIFYING AND REPORTING

All mumps cases under investigation should be reported to public health authorities in a timely manner. Confirmed mumps cases, as per the case definition, should be part of provincial/territorial and national reporting of mumps. Please check with your province for reporting guidelines.

CASE DEFINITIONS

In the absence of immunization in the previous 28 days, a confirmed case can be defined as any of the following:

- mumps virus detection or isolation from an appropriate specimen (buccal swab is preferred);

- positive serologic test for mumps IgM antibody in a person who has mumps-compatible clinical illness (see clinical case definition);

- significant rise (four-fold or greater) or seroconversion in mumps IgG titre;

- mumps-compatible clinical illness (see clinical case definition) in a person with an epidemiologic link to a laboratory-confirmed case.

A clinical or probable case can be defined as an acute onset of unilateral or bilateral parotitis lasting longer than 2 days without other apparent cause.

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS

Detection, isolation, and genotyping of mumps are performed at the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML).

Testing by IgM class antibody detection and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay are not sufficiently reliable to diagnose mumps infection. In addition to clinical illness, epidemiologically confirmed cases without another diagnosis for parotitis should have an established epidemiologic link with a laboratory-confirmed case. If no epidemiologic link exists, a person with clinical symptoms should be managed by public health as a probable mumps case (see the definition for a probable case below).

SEROLOGY

Mumps-specific IgM class antibody testing has been shown to be a poor predictor for mumps diagnosis in partially immunized populations, with detection in only 30% of acute cases.

To test for mumps-specific IgM-class antibody, an acute (first) specimen should be collected upon presentation of symptoms with a convalescent (second) specimen collected at least 10 days (ideal) or up to 3 weeks after the first sample. Testing should show a fourfold or greater rise in tire between the acute and convalescent sera or seroconversion (i.e., negative to positive result) to indicate an acute mumps infection.

Collecting acute and convalescent serum specimens 10-14 days later may show seroconversion for IgM and/or IgG antibody in cases where the mumps RT-PCR assay and IgM antibody were negative or indeterminate at the onset of illness, thus, identifying additional cases.

If the individual has not travelled to areas with mumps or established epidemiologic links to confirmed cases, one should be cautious of false-positive IgM results.

SPECIMEN COLLECTION

Mumps virus is an RNA virus, therefore, RT-PCR is commonly used for virus detection. Because IgM testing has suboptimal sensitivity, RT-PCR is the main diagnostic approach for laboratory confirmation. For the RT-PCR assay, saliva should be collected from the buccal cavity within the first 3-5 days of symptom onset. It is important to note, however, that the timing of the specimen collection in relation to symptom onset, as well as the integrity of the specimen (i.e., rapid specimen processing) can influence the sensitivity of RT-PCR.

Genotyping methods are available at NML to differentiate between wild and vaccine types of the virus, especially if symptoms develop in an individual within 28 days of receiving the vaccine. Genotyping is also useful for linking outbreaks, cases, and tracking importations or eliminations of particular strains.

More information about the laboratory diagnosis of mumps can be found in PHAC: Supplement – Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Mumps Outbreaks in Canada

What measures should be taken for a suspected Mumps case or contact?

Mumps is preventable by the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) or measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) vaccine, which is part of the regular childhood immunization series in Canada. The best way to protect yourself, your child, and your community from mumps, and prevent outbreaks, is through immunization. Two doses of the vaccine offer 76-95% protection against mumps and one dose offers 62-91%.

If you or your child has symptoms of mumps, call your health care provider right away.

Because mumps is highly contagious, it is important to stay home and isolate from others if you are infected. Measures to reduce transmission include:

- Good hand hygiene: wash hands often with soap and water, or use alcohol hand rub

- Avoid sharing items that could be contaminated with saliva such as water bottles, drinking glasses, utensils, etc.

- Clean and disinfect high touch/potentially-contaminated surfaces

- Cover coughs or sneezes with a tissue or a forearm

TREATMENT

There is no cure for mumps. Sick children and adults should stay home from work and school for at least five days after the onset of swelling. Since infections are typically mild, health care providers usually recommend supportive care to help the body fight off the infection. Supportive care can include medication (e.g., pain relievers) to reduce fever and discomfort, drinking plenty of fluids, eating health foods, and getting plenty of rest.

Antibiotics are not effective in treating mumps because mumps is a viral infection and not caused by bacteria. Antibiotics only work against bacterial infections.

What is happening with the current outbreak of Mumps?

EPIDEMIOLOGY

CANADA

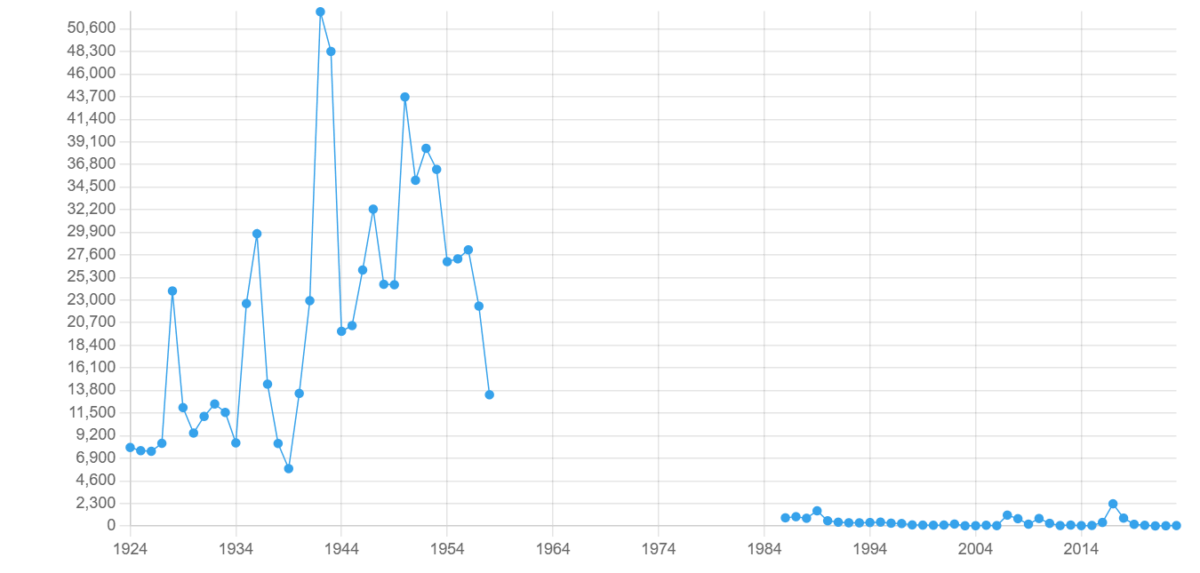

People born in Canada before 1970 have likely had mumps already and are generally presumed to be protected because of this past infection. After the introduction of routine immunization programs for mumps in Canada in 1969, the number of annual cases reported each year decreased by more than 99% from an average of 33,000 cases per year between 1951 to 1955, to approximately 180 cases per year between 2011 to 2013. Mumps remains endemic in Canada, however, since 1970, cases have become sporadic and often associated with outbreaks.

Figure 1. Number of reported cases of mumps in Canada, 1924-2023

Publicly-available data on mumps cases and rates was not available for Nunavut, Yukon, Northwest Territories, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick.

Manitoba

The latest publicly-available data on mumps in Manitoba is from the 2017 outbreak in the province. Between September 01, 2016 and April 21, 2017, 323 confirmed cases were identified in Manitoba. In comparison, the previous usual incidence of mumps in the province, as of 2017, was four to five cases per year.

Saskatchewan

The latest publicly-available data on mumps in Saskatchewan is from 2018. In 2018, Saskatchewan recorded 14 cases of mumps, of which, one was in child under one year of age who was ineligible to receive the vaccine, one was in a preschooler who was fully immunized, six were in school-aged children who were fully immunized, two were in young adults who were fully immunized, and four were in adults aged 20-60 years who were inadequately immunized. Eleven of the 14 cases in 2018 were from a mumps outbreak in a northern Saskatchewan community that began in October 2017 and was declared over in May 2018.

Table 1. Number of mumps cases in Saskatchewan, 2012-2017

| Year | Number of cases of mumps |

| 2012 | 0 cases |

| 2013 | 2 cases |

| 2014 | 0 cases |

| 2015 | 1 case |

| 2016 | 1 case |

| 2017 | 77 cases |

| 2018 | 14 cases |

Alberta

Mumps data in Alberta is available through 2023. As of 2023, Alberta reported 16 cases of mumps (0.34 cases per 100,000 population). Outbreaks occur sporadically in the province, with the latest outbreak in 2017. Annual case counts and rates are included in Table 2 for 2000-2023.

Table 2. Annual incidence and rates of mumps in Alberta, 2000-2023

| Year | Number of cases of mumps | Rate per 100,000 population |

| 2000 | 13 | 0.43 |

| 2001 | 36 | 1.18 |

| 2002 | 172 | 5.50 |

| 2003 | 4 | 0.13 |

| 2004 | 3 | 0.09 |

| 2005 | 16 | 0.48 |

| 2006 | 8 | 0.23 |

| 2007 | 243 | 6.91 |

| 2008 | 309 | 8.59 |

| 2009 | 26 | 0.71 |

| 2010 | 9 | 0.24 |

| 2011 | 12 | 0.32 |

| 2012 | 6 | 0.15 |

| 2013 | 5 | 0.13 |

| 2014 | 8 | 0.20 |

| 2015 | 4 | 0.10 |

| 2016 | 8 | 0.19 |

| 2017 | 115 | 2.71 |

| 2018 | 19 | 0.44 |

| 2019 | 33 | 0.76 |

| 2020 | 14 | 0.32 |

| 2021 | 5 | 0.11 |

| 2022 | 9 | 0.20 |

| 2023 | 16 | 0.34 |

By 2024, 80.1% of toddlers in Alberta received the first dose of the MMR vaccine by age two while 68.1% received the second dose by age two. By age seven, 71.6% of children had received the second dose. More detailed information on vaccine coverage rates for mumps by dose, age group, and health region in Alberta is available on Alberta’s Childhood Immunization Coverage Dashboard .

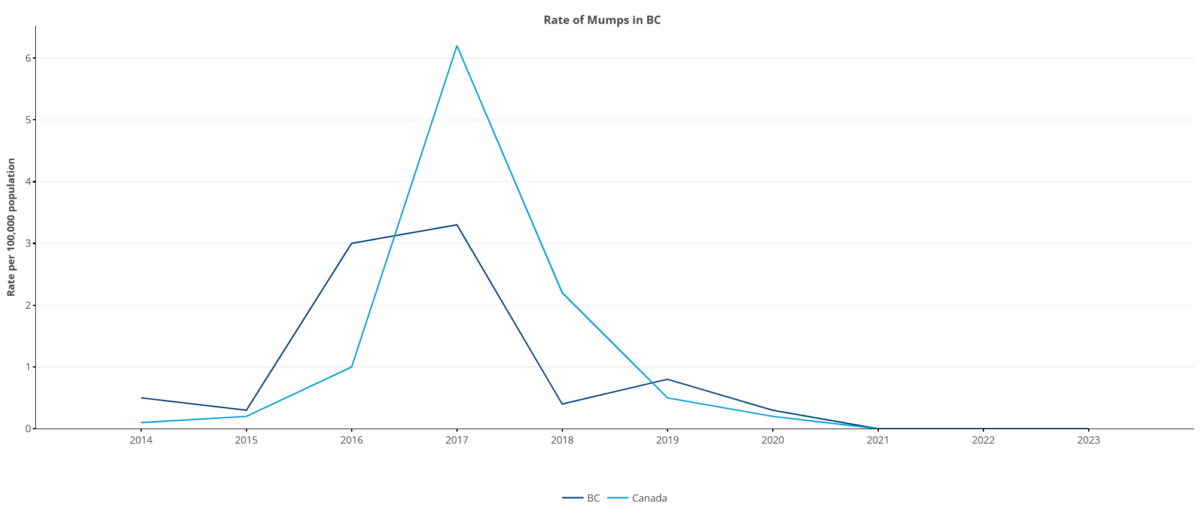

British Columbia

Mumps data in British Columbia is available through 2023. British Columbia experienced outbreaks of mumps in 2016 and 2017. The latest data is included in the table below.

Table 3. Number of mumps cases in British Columbia, 2014-2023

| Year | Number of cases of mumps | Rate per 100,000 population |

| 2014 | 23 | 0.5 |

| 2015 | 13 | 0.3 |

| 2016 | 148 | 3.0 |

| 2017 | 162 | 3.3 |

| 2018 | 19 | 0.4 |

| 2019 | 41 | 0.8 |

| 2020 | 18 | 0.3 |

| 2021 | 0 | 0 |

| 2022 | 0 | 0 |

| 2023 | 2 | 0 |

Figure 2. Rate of mumps in British Columbia, 2014-2023

Ontario

As of November 19, 2025, 29 cases of confirmed and probable cases (7.1 cases per 1,000,000 population) were recorded in Ontario for 2025. This is slightly higher than the five-year average for the same period (January-November) which is 25 cases (1.6 cases per 1,000,000 population).

For up-to-date surveillance data on mumps in Ontario, please visit Public Health Ontario’s Infectious Diseases Surveillance Reports webpage and see the latest “Diseases of Public Health Significance Cases” reports.

Prince Edward Island

There were no reported cases of mumps in Prince Edward Island between 2018 and 2024. Updated data on mumps cases can be found in the annual report of notifiable diseases produced by the province’s Chief Public Health Office.

What is the current risk for Canadians from Mumps?

Canadians who have not had mumps or who were not immunized in accordance with the recommended immunization schedule are at risk of contracting mumps. Those born before 1970 are generally assumed protected by natural infection and are, therefore, at lower risk. However, certain groups, regardless of the year they were born or previously receiving vaccinations, are more susceptible to the virus due to higher risks of exposure. These groups include:

- health care workers;

- military personnel;

- students in post-secondary educational settings; and

- travellers to destinations outside of Canada

See the Vaccination section below for information on high-risk groups and recommended vaccinations according to the Canadian Immunization Guide.

VACCINATION

Since the authorization of the mumps vaccine in Canada in 1969 and the subsequent introduction of the routine two-dose MMR vaccination series in 1996/97, the number of reported mumps cases nationally has decreased by more than 99%.

The mumps vaccine is included in the MMR and MMRV vaccines which are part of Canada’s routine childhood immunization series. The timing of the routine childhood immunization series varies by province and territory, but the first dose of mumps-containing vaccine is typically administered at 12-15 months of age. The second dose should be administered at 18 months of age or anytime thereafter, but no later than around school entry.

People who have not previously been infected with mumps or who have not been vaccinated against mumps are at higher risk of infection.

Children

Children and adolescents who did not receive the mumps vaccine in the routine childhood immunization series should receive two doses of any mumps-containing (MMR or MMRV) vaccine. The MMRV vaccine may be used in healthy children between the ages of 12 months and 13 years.

Adults born in or after 1970

Because the second dose of the MMR vaccine was not incorporated into Canada’s routine childhood immunization series until 1996/1997, individuals born between 1970 and 1996 are less likely to have received this second dose during childhood. Therefore, they are advised to receive a second dose to be fully protected.

Adults born in or after 1970 who were not vaccinated against mumps or who have not been previously infected should receive one dose of MMR, particularly if they are planning to travel abroad.

Susceptible adults (such as health care workers and military personnel, travellers to destinations outside of Canada, and students in post-secondary educational settings) born in or after 1970 should receive two doses of MMR vaccine. Table 4 summarizes the number of recommended doses of the MMR vaccine for susceptible adults born in or after 1970.

Table 4. Number of recommended MMR vaccine doses for susceptible groups born in or after 1970

| Susceptible Group | Recommended number of MMR vaccine doses |

| Adults born in Canada between 1970 and 1996 who received only one dose of the MMR vaccine during childhood | 1 dose |

| Susceptible adults born in or after 1970 who have not been vaccinated or who have not been previously infected | 1 dose |

| Susceptible health care workers and military personnel born in or after 1970 | 2 doses |

| Susceptible adults born in or after 1970 travelling to destinations outside of Canada | 2 doses |

| Susceptible students in post-secondary educational settings born in or after 1970 | 2 doses |

Adults born before 1970

Most adults born before 1970 are generally presumed to have acquired natural immunity to mumps and therefore, do not need to be vaccinated. However, certain groups born before 1970 are more susceptible to the virus due to higher risks of exposure and should receive the MMR vaccine. The number of recommended doses of MMR vaccine for susceptible groups born before 1970 are listed in Table 5 below.

Table 5. Number of recommended MMR vaccine doses for susceptible groups born before 1970

| Susceptible Group | Recommended number of MMR vaccine doses |

| Susceptible health care workers and military personnel born before 1970 | 2 doses |

| Susceptible persons born before 1970 travelling to destinations outside of Canada | 1 dose |

| Susceptible students in post-secondary educational settings born before 1970 | 1 dose |

TRAVEL RECOMMENDATIONS

Mumps is a very common infection in many parts of the world. Anyone traveling outside of North America is advised to:

- visit their health care provider at least 6 weeks before they leave;

- make sure their mumps-containing immunizations are up to date; and

- check the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Travel Health Notices webpage for notices regarding mumps.