Are you looking for the PHAC guidance document for practitioners?

Updated February 3, 2025

NCCID Disease Debriefs provide Canadian public health practitioners and clinicians with up-to-date reviews of essential information on prominent infectious diseases for Canadian public health practice. While not a formal literature review, information is gathered from key sources including the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO) and peer-reviewed literature.

This disease debrief was prepared by Ayel Batac. Questions, comments, and suggestions regarding this disease brief are most welcome and can be sent to nccid@umanitoba.ca

What are Disease Debriefs? To find out more about how information is collected, see our page dedicated to the Disease Debriefs.

Questions Addressed in this debrief:

- What are important characteristics of the mpox virus?

- What is happening with current outbreaks of mpox?

- What is the current risk for Canadians from mpox?

- What measures should be taken for a suspected mpox case or contact?

What are important characteristics of the mpox virus?

Cause

Mpox virus (formerly Monkeypox) is a zoonotic, double-stranded DNA virus in the Orthopoxvirus genus (Poxviridae family), which also includes the variola virus (smallpox), cowpox virus, and vaccinia virus (used in smallpox vaccines).

The natural reservoir of the mpox virus has not been definitively identified. However, evidence suggests that certain rodents, such as squirrels, Gambian pouched rats, and dormice, are the most likely hosts. Non-human primates can be infected but are not primary reservoirs. Ongoing research continues to investigate the animal species and ecological factors responsible for maintaining the virus in nature.

PHAC: Mpox: For health professionals

Clades and Variants

Recent research has reclassified the mpox virus into two distinct clades, now officially referred to as Clade I (formerly the Central African or Congo Basin clade) and Clade II (formerly the West African clade). Each clade has further subdivisions: Clade I includes subclades Ia and Ib, while Clade II includes subclades IIa and IIb. Clade IIb has been specifically associated with the 2022 multi-country outbreak, which marked a significant global spread of the virus, particularly outside of endemic regions. This reclassification highlights the genetic and geographic differences between these strains, as well as their varying clinical and epidemiological characteristics.

- Clade I (Central African): Historically associated with more severe disease presentations and a higher fatality rate, and is believed to be more transmissible compared to Clade II. Clade I is endemic to Central Africa, particularly the Democratic Republic of the Congo and surrounding regions.

- Clade Ia: Endemic to the Democratic Republic of the Congo and neighbouring regions, this sub-lineage is associated with a case fatality rate (CFR) of approximately 3.6% in 2024. Clade Ia is responsible for outbreaks in both urban and rural areas, with sustained transmission in sexual and household networks.

- Clade Ib: A newly emerging sub-lineage of Clade I, Clade Ib has been associated with a lower CFR compared to Clade Ia. While primarily affecting regions within Central Africa, Clade Ib has been detected beyond Africa as of 2024, raising concerns about its potential for international spread.

- Clade II (West African): Typically associated with milder disease and a lower fatality rate.

- Clade IIa: Historically confined to endemic areas in West Africa (e.g., Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Guinea). Sustained community transmission of this subtype was first reported in 2024.

- Clade IIb: Responsible for the global 2022 outbreak, which has shown sustained human-to-human transmission outside endemic regions. Clade IIb has been the dominant strain in non-endemic regions such as the Americas, Europe, and parts of Asia. Typically associated with milder disease presentations and a lower CFR compared to Clade I.

Key Differences

- Clade Ia: More virulent, with a case fatality rate of ~3.6%, primarily confined to Central Africa, and associated with severe disease presentations.

- Clade Ib: Less virulent than Clade Ia, with a lower case fatality rate, largely confined to Central Africa but recently detected in travel-related cases beyond Africa as of 2024, raising concerns about potential international spread.

- Clade IIa: Previously limited to West Africa, with the first indications of wider community transmission emerging in 2024.

- Clade IIb: The primary driver of the global outbreak starting in 2022, with notable transmission in non-endemic areas, particularly among high-risk populations.

PHAC: Mpox: How it Spreads, Prevention, and Risks

CDC: Mpox in the United States and Around the World: Current Situation

CDC: Concurrent Clade I and Clade II Monkeypox Virus Circulation, Cameroon, 1979–2022

WHO: Monkeypox: Experts Give Virus Variants New Names

Transmission

Mpox virus transmission occurs through direct or indirect contact with the body fluids, respiratory secretions, or lesion material from infected animals or humans, as well as through contaminated materials such as bedding or clothing.

Animal-to-human transmission

- Can occur via bites, scratches, or direct contact with the blood, bodily fluids, or lesions of an infected animal.

- Handling or consuming bush meat from infected animals also presents a transmission risk.

Human-to-human transmission

- Primarily occurs through respiratory droplets during prolonged, close face-to-face contact.

- Contact with lesion material, scabs, or body fluids of an infected person can also result in transmission.

- The 2022 outbreak emphasized the role of intimate physical contact, including sexual contact, in transmission.

Entry points

- The virus may enter the body through broken skin (even if not visibly damaged), the respiratory tract, or mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, or mouth.

Additional considerations

- Transmission can also occur through contact with contaminated materials, such as clothing, bedding, or towels used by an infected person.

While respiratory transmission is possible, it requires prolonged face-to-face contact; brief interactions are less likely to result in transmission.

Table 1. Comparison of transmission dynamics between Clade I (Central African) and Clade II (West African) mpox.

| Clade I (Central African) | Clade II (West African) |

|---|---|

| Higher transmissibility: Clade I is associated with more efficient human-to-human transmission, potentially due to factors such as higher viral load or longer viral shedding period, although this remains a hypothesis. | Lower transmissibility: Clade II has historically been associated with more limited human-to-human transmission, resulting in smaller outbreak sizes compared to Clade I. |

| Greater severity: Clade I tends to cause more severe disease, which could increase transmission opportunities, particularly in caregiving or healthcare settings. | Milder disease course: Clade II generally results in less severe symptoms and a lower case fatality rate. This may lead to fewer lesions and lower viral loads, potentially reducing the ease of transmission. |

| Larger household clusters: Clade I has been observed to cause larger clusters of cases within households and communities, with more extensive chains of transmission documented in Central Africa. |

PHAC: Mpox: How it Spreads, Prevention, and Risks

CDC: Mpox in the United States and Around the World: Current Situation

CDC: Concurrent Clade I and Clade II Monkeypox Virus Circulation, Cameroon, 1979–2022

WHO: Monkeypox: Experts Give Virus Variants New Names

Signs, Symptoms, and Severity

Mpox symptoms follow a specific progression, with a key distinguishing feature being the presence of swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy). Lymphadenopathy can be localized to areas such as the neck, armpits, or groin or generalized across multiple regions of the body. The illness typically resolves on its own within 2 to 4 weeks, but the severity can range from mild presentations, such as a single lesion, to disseminated, multi-organ infection. While asymptomatic infections are not confirmed, this remains an area of ongoing research.

Incubation period

- The incubation period for mpox ranges from 3 to 21 days, with the 2022 outbreak generally showing an incubation period of 7 to 10 days.

Clinical presentation

Mpox can present with systemic symptoms, skin or mucosal lesions, or both. Systemic symptoms often appear 0 to 5 days before the onset of lesions, though they may also occur simultaneously with or after the appearance of lesions.

General symptoms

- Fever and chills

- Headache

- Muscle aches, back pain, arthralgia (joint pain), and myalgia (muscle pain)

- Fatigue and exhaustion

- Sore throat (pharyngitis)

- Swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy)

- Rectal pain (proctitis)

- Gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., vomiting, diarrhea)

The 2022 multi-country outbreak frequently reported pharyngitis symptoms (sore throat) and proctitis symptoms (rectal pain) as prominent features.

Rash progression and skin lesions

A rash typically develops 1 to 3 days after systemic symptoms like fever, although this timing can vary. Lesions are often painful and may become itchy during the healing phase. They can occur anywhere on the body, including:

- Mouth and pharynx

- Genitals and anal areas

- Palms of the hands and soles of the feet

Lesions progress through the following stages:

- Macules (flat lesions)

- Papules (raised lesions)

- Vesicles (fluid-filled blisters)

- Pustules

- Ulcers and scabs that eventually fall off.

In most cases, lesions in the same body area evolve synchronously, but atypical presentations with asynchronous rashes can occur. Lesions generally last for 2 to 4 weeks.

Sourced from: PHAC; PHAC reproduced with permission from UK Health Security Agency

Complications

While most cases of mpox are mild, severe cases can occur, particularly in young children, pregnant individuals, and the immunocompromised. Complications may include:

- Proctitis

- Pharyngitis

- Bacterial superinfection of lesions

- Corneal infections, potentially leading to vision loss

- Sepsis

- Pneumonia

- Myocarditis

- Encephalitis

PHAC: Mpox: For health professionals – Clinical manifestations

Case fatality rates (CFRs)

- Clade Ia: CFR of approximately 3.6% in 2024.

- Clade Ib: Preliminary evidence suggests a lower CFR compared to Clade Ia.

- Clade II: Historically, CFRs in endemic areas range from 1% to 3%, but fatalities are rare in non-endemic regions. For example, no deaths have been reported in Canada to date.

- CFR variability reflects differences in clades, population factors, healthcare access, and supportive care availability.

PHAC: Mpox: For health professionals – Clinical manifestations

Co-infections

Mpox frequently co-occurs with other sexually transmissible and blood-borne infections (STBBIs). PHAC recommends that healthcare providers test for infections such as syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, herpes simplex, and HIV in suspected mpox cases, particularly when transmission may have occurred via sexual contact.

Recent observations in clinical presentation

During the 2022–2023 multi-country outbreak, health organizations reported atypical clinical presentations:

- Localized lesions: Lesions were frequently localized to the genital, perineal/perianal, or peri-oral areas rather than being widespread.

- Mucosal lesions: Increased presentation of lesions in the mouth, eyes, and genital/anal areas was observed.

- Asynchronous lesions: In some cases, rashes appeared asynchronously, with new lesions emerging at different times rather than uniformly progressing.

- Prodrome variability: Some individuals experienced a rash prior to the onset of traditional symptoms like fever and malaise.

- Symptoms of note: Anal pain, rectal bleeding, and swollen lymph nodes were common features.

CDC: The CDC Domestic Mpox Response — United States, 2022–2023

CDC: Detection and Transmission of Mpox Virus During the 2022 Clade IIb Outbreak

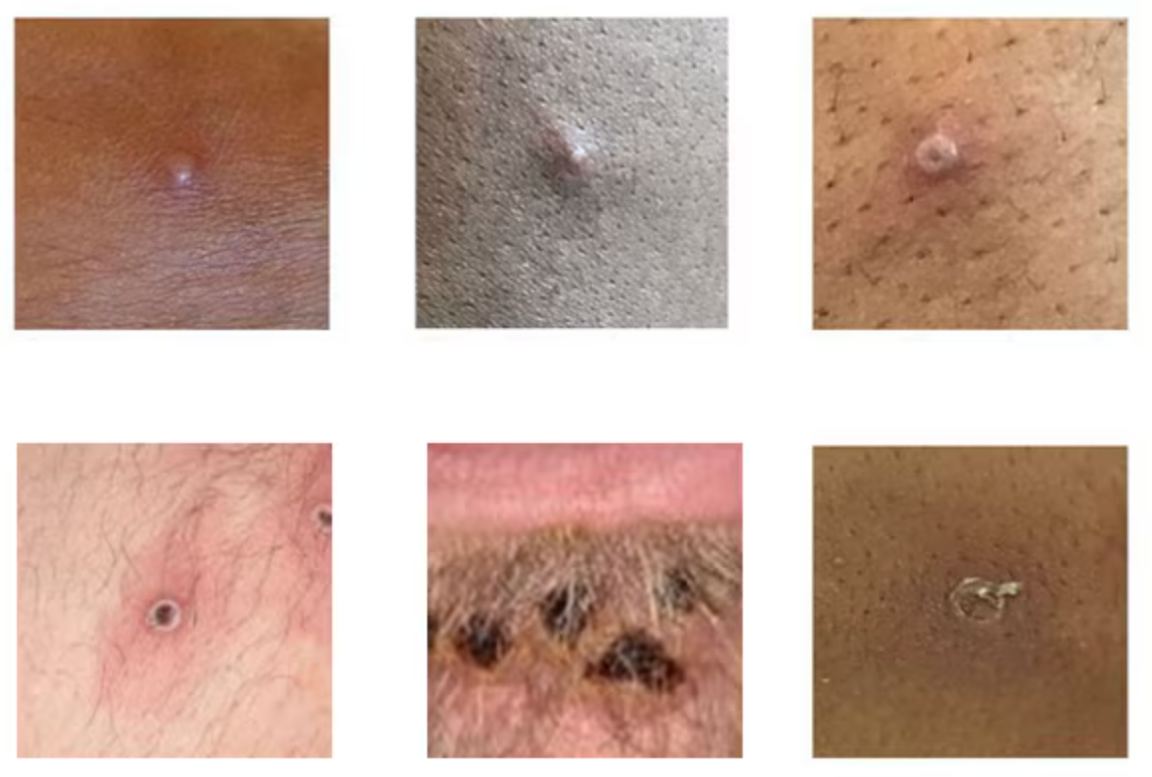

Figure 2. Mpox lesions are firm or rubbery, clearly defined, embedded deep in the skin, and often develop a central indentation, appearing like a small dot or depression on top of the lesion (umbilication).

Source: UK Health Security Agency

The WHO’s publication of the “Atlas of Mpox Lesions” (April 2023) provides an essential visual reference for identifying mpox lesions in various areas, supporting healthcare providers in diagnosis.

WHO: Atlas of mpox lesions: a tool for clinical researchers

Clade-specific differences

- Clade I (Central African): Associated with more severe illness, higher lesion counts, and increased systemic symptoms such as severe lymphadenopathy and respiratory distress. Mortality rates for Clade I have historically been higher, ranging from approximately 1.4% to over 10% in certain outbreaks.

- Clade II (West African): Generally associated with milder disease and lower mortality rates, approximately 0.1% to 3.6%. Most of the 2022 outbreak cases were caused by Clade IIb, which showed more localized rashes and a higher prevalence of cases involving sexual networks.

Johns Hopkins University: Situation Update: October 30, 2024 Mpox Virus: Clade I and Clade II

Duration and severity of illness

- Duration: Illness typically lasts 2–4 weeks.

- Risk factors for severe disease:

- Young children, pregnant or breastfeeding individuals, and those with underlying health conditions.

- Immunocompromised individuals, particularly those with advanced HIV infection, are at increased risk for severe disease. Studies in the US found that the majority of severe cases were in people with significant immunosuppression.

PHAC: Mpox: For health professionals – Clinical manifestations

Clinical management and surveillance

- Supportive care is the primary approach to mpox management, focusing on symptom relief, hydration, and monitoring for complications such as secondary infections, pneumonia, or encephalitis.

- Tecovirimat (TPOXX) may be considered in select cases for patients at high risk of severe disease, including those who are immunocompromised, pregnant, or experiencing extensive lesions. However, it is not currently approved by Health Canada for mpox treatment and is used off-label based on clinical discretion.

- Imvamune® is the recommended vaccine for mpox prevention, authorized for adults at high risk of exposure. It is used both pre-exposure for high-risk populations and post-exposure following contact with a confirmed or probable case.

- Mpox cases must be reported to public health authorities according to provincial, territorial, or local protocols. PHAC provides a standardized case report form to support national surveillance efforts.

- Public health surveillance focuses on outbreak monitoring through data collection from provinces and territories. This helps track transmission patterns, assess high-risk populations, and inform public health interventions.

- Epidemiological updates guide vaccination and containment strategies, ensuring public health responses are tailored to evolving transmission trends. Surveillance findings are used to support vaccine distribution, risk communication, and infection prevention measures.

PHAC: Mpox: For health professionals – Management and treatment

PHAC: Mpox: For health professionals – Surveillance

Epidemiology

As of November 30, 2024, a cumulative total of 117,663 laboratory-confirmed mpox cases and 263 deaths have been reported globally across 127 countries since the onset of the outbreak in 2022. The case fatality rate (CFR) is globally estimated at 0.2%, though it varies significantly between Clades I and II.

Global distribution of cases

The Americas accounts for the largest share of global mpox cases, contributing 57.3% of all cases, followed by the European Region (24.4%) and the African Region (12.5%). The outbreak has significantly impacted high-risk populations, with transmission dynamics varying across regions and clades.

- Africa: The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) remains a hotspot for Clade I, reporting sustained endemic transmission in both rural and urban areas, including Kinshasa. In the DRC, outbreaks involve both sexual networks and household transmissions, with children and adults affected. Lower incidence rates are observed in individuals over 50 years old, likely due to pre-existing immunity from smallpox vaccination.

- The Americas: The Americas have reported 66,806 confirmed cases and 151 deaths between 2022 and November 2024, with North America bearing the highest burden. The United States reported 34,349 cases and 63 deaths, followed by Mexico (4,192 cases, 35 deaths) and Canada (1,836 cases). In 2024 alone, 5,142 cases and 7 deaths were reported in 15 countries in the Americas, with the United States recording the largest number of cases. Canada documented 365 cases, predominantly in Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta. Notably, Clade Ib emerged in the Americas for the first time, with cases reported in travellers returning from East Africa.

- Europe: Europe has reported 28,682 confirmed cases since 2022, primarily in men who have sex with men (MSM). While most cases are attributed to Clade IIb, imported Clade Ib cases, including a notable case in Sweden in 2024, demonstrate the potential for intercontinental spread.

- Other regions: Countries in the Eastern Mediterranean, Western Pacific, and Southeast Asia regions collectively reported approximately 10,000 cases. Australia experienced an unprecedented rise in cases, reporting 1,352 cases in 2024, highlighting the global spread of Clade IIb.

Clade-specific insights

- Clade Ia: Primarily reported in Central Africa, particularly in the DRC and Central African Republic. Transmission in urban centres like Kinshasa includes sexual networks and household spread.

- Clade Ib: Rapidly expanding in Eastern Africa, including Uganda, Kenya, and neighbouring countries, with travel-related cases identified in Sweden, Germany, and Canada.

- Clade IIa: First identified in West Africa (e.g., Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Guinea) in 2024, demonstrating sustained community transmission for the first time.

- Clade IIb: The dominant strain outside Africa, responsible for the multi-country outbreaks since 2022, with transmission primarily through sexual contact in high-risk populations.

Age and sex distribution

Globally, males account for 96.3% of cases, with a median age of 34 years (IQR: 29–41). Males aged 18–44 years represent 79.3% of cases. Females comprise 3.7% of cases, with most reported in the Americas (76%) and Europe (14%). Among women, sexual encounters were the most commonly reported mode of transmission (52%).

Cases among pregnant or recently pregnant women include 60 cases, with a median age of 26.5 years (IQR: 22–31). Among these, three were in the first trimester, 12 in the second, and nine in the third. While no ICU admissions or deaths were reported among pregnant individuals, 13 cases required hospitalization, with sexual contact identified as the predominant transmission route.

Children aged 0–17 years account for 1.3% of cases, with 64% reported in the Americas. Among these, 361 cases (0.4%) were in children aged 0–4 years.

HIV status and transmission dynamics

Among cases with known HIV status, 51.8% (19,128/36,921) were people living with HIV. Sexual encounters remain the predominant mode of transmission for individuals with HIV, reflecting trends seen across the general outbreak population. However, HIV status data is unavailable for most cases, limiting comprehensive analysis.

The primary mode of transmission globally was sexual contact, reported in 84.5% of cases with known data (19,707/23,312). Party settings involving sexual contact were the most commonly reported exposure setting, accounting for 35.6% of all transmission events. Among cases with detailed sexual behavior data, 86.7% identified as MSM, underscoring the outbreak’s significant impact on this group.

Case fatality rates and vulnerable populations

The CFR varies significantly by clade and region. In the DRC, where Clade Ia is dominant, the CFR is approximately 3.6%, reflecting limited healthcare access in remote areas. In Kinshasa, where Clade Ia and Clade Ib co-circulate, the CFR is 0.3%, while North and South Kivu, dominated by Clade Ib, report the lowest CFR at 0.2%. These differences may reflect variations in healthcare access, population demographics, and case reporting rather than inherent differences in virulence.

Healthcare worker cases

A total of 1,485 cases were reported among healthcare workers, though the majority appear to result from community-based exposures rather than occupational exposure. Investigations are ongoing to understand the extent of workplace-related transmission.

Regional trends from the Pan American Health Organization

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) highlights that most cases in the Americas were identified through HIV care services, sexual health clinics, and primary healthcare facilities, emphasizing the role of sexual health services in managing the outbreak. While the Americas remain the most affected region, with North America bearing the highest burden, the data underscore the importance of targeted interventions in high-risk populations.

PHAC: Mpox epidemiology update

CDC: Mpox in the United States and Around the World: Current Situation

WHO: 2022-24 Mpox (Monkeypox) Outbreak: Global Trends

WHO: Multi-country outbreak of mpox December 2024

Source: Pan American Health Organization

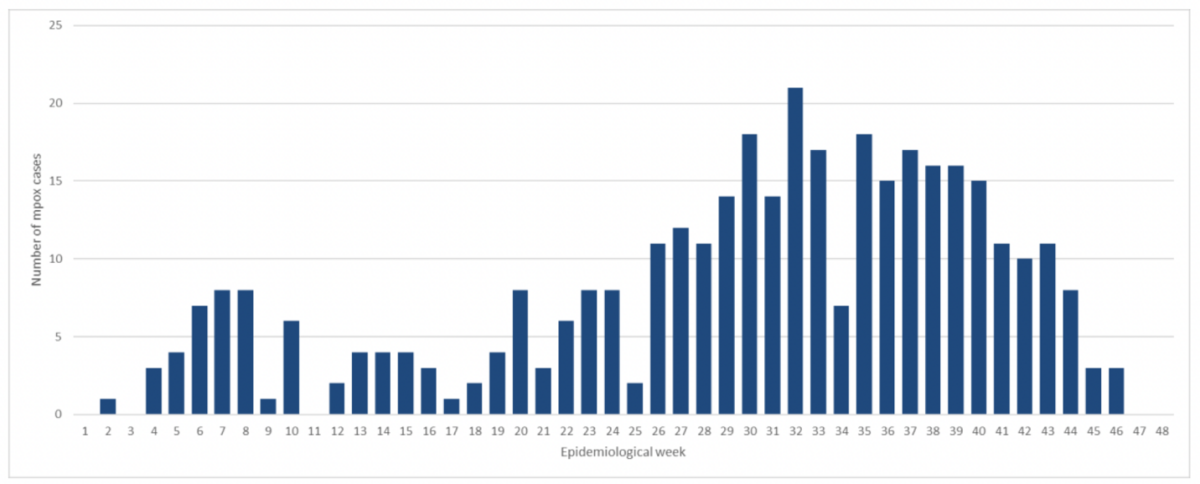

As of December 23, 2024, Canada has reported a cumulative total of 1,887 confirmed mpox cases since the onset of the outbreak in 2022, with 414 cases occurring in 2024. Between epidemiological week (EW) 1 and EW 48 of 2024, 365 confirmed cases were documented, averaging seven cases per week, indicating low-level, ongoing transmission throughout the year. Hospitalizations remain minimal, with only six hospitalizations in 2024 and a cumulative total of 52 hospitalizations since 2022. Importantly, no deaths have been reported during the outbreak in Canada.

The outbreak in Canada has predominantly been caused by Clade IIb, in line with global trends. However, in 2024, one case of Clade Ib was detected, marking a rare introduction of this strain. Mpox cases have been reported across 10 provinces and territories since 2022, though only five provinces/territories were affected in 2024.

Geographic distribution

Mpox cases in Canada are primarily concentrated in a few provinces. Ontario has reported the highest number of cases, with n = 1,017, followed by Quebec (n = 598), British Columbia (n = 287), and Alberta (n = 53). Manitoba and Nova Scotia have each reported n = 2 cases. No cases have been identified in Prince Edward Island, the Northwest Territories, or Nunavut.

Demographics

The outbreak has disproportionately affected men, who account for 96–97% of cases, reflecting a consistent trend over time. The majority of cases are within the 18–49-year age group, comprising 85% of all reported cases. Within this demographic, the 30–39-year age group is the most affected, representing 39% of cases in 2024. Notably, no cases have been reported among minors under 18 years of age, underscoring that the outbreak predominantly impacts adults.

Among high-risk groups, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) represent 95% of cases, while 21% of cases are among people living with HIV. These findings highlight the significant impact of mpox on these specific populations.

Hospitalizations and outcomes

Of the 336 cases with available hospitalization data in 2024, only 1.5% (n = 5) required hospitalization, suggesting that while mpox caused symptomatic illness, severe cases were rare. Across the entire outbreak, hospitalizations have remained low, and no fatalities have been reported, reflecting effective clinical management and public health interventions.

Surveillance and definitions

PHAC has implemented detailed surveillance measures to monitor the outbreak. A suspected case is defined as an individual with unexplained acute rashes or lesions and at least one associated symptom, such as fever or swollen lymph nodes. A probable case meets the suspected case criteria and has an epidemiological link to a confirmed or probable case or a setting where mpox transmission is suspected. A confirmed case requires laboratory confirmation through PCR or DNA sequencing.

PAHO: Epidemiological Update Mpox in the Americas Region 20 December 2024

PHAC: Mpox epidemiology update

PHAC: National case definition: Mpox (monkeypox)

Laboratory Diagnosis

The diagnosis of mpox is confirmed through the detection of monkeypox virus (MPXV) DNA by PCR or the isolation of MPXV from viral culture. Specimen collection primarily relies on skin lesion material, which provides the best samples for both PCR testing and viral culture. This includes swabs of lesion surfaces or fluids, lesion crusts (scabs), and roofs of multiple lesions. Skin lesion material should be placed in an empty, sterile container for transport. While formalin-fixed or paraffin-embedded tissues can be used for PCR, they are unsuitable for viral culture. Although Viral Transport Media (VTM) is not recommended for specimen collection, samples collected in VTM will still be accepted for diagnostic testing if already prepared. Currently, serology is not used as a diagnostic tool for mpox.

The National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) provides validated testing for mpox through its Special Pathogens Program. The laboratory has developed molecular assays to differentiate between Clade I and Clade II MPXV and sequences all positive mpox samples under specific criteria. These include Clade I positivity on PCR testing or patient presentations involving unique clinical, travel, or contact histories. Clinicians unable to collect lesion swabs are encouraged to contact the NML or their local public health laboratory to discuss alternative specimen types or protocols for specimen transport and handling.

Differential diagnosis for mpox includes various infectious and non-infectious conditions, as mpox rashes may resemble other diseases. Lymphadenopathy, a distinguishing feature of mpox, can help differentiate it from similar conditions. Diseases to consider include varicella zoster (chickenpox, shingles), herpes simplex, lymphogranuloma venereum, gonorrhea, hand-foot-mouth disease, molluscum contagiosum, syphilis, human papillomavirus infection, chancroid, and orf (rare). While smallpox can present similarly to mpox, it is no longer a consideration for differential diagnosis due to its eradication in 1980, except in the case of a laboratory breach.

Co-infections with sexually transmissible and blood-borne infections (STBBIs) have been frequently reported during the 2022 outbreak. As such, clinicians should consider testing for HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and other STBBIs in individuals suspected of acquiring mpox through sexual contact. This approach ensures comprehensive patient evaluation and addresses possible concurrent infections.

Clinicians evaluating and sampling patients suspected of having mpox must wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) to ensure safety. Public health laboratories should be consulted for guidance on specimen handling and transport. These protocols, combined with accurate differential diagnosis and thorough clinical evaluation, are essential to managing and diagnosing mpox effectively.

PHAC: Mpox (monkeypox): For health professionals – Diagnosis (November 2024)

Prevention and Control

On May 24, 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the Strategic Framework for Enhancing Prevention and Control of Mpox (2024–2027). This roadmap aims to guide health authorities, communities, and stakeholders worldwide in controlling mpox outbreaks, advancing research and access to countermeasures, and minimizing zoonotic transmission. The framework underscores integrating efforts across health programs, including epidemiological surveillance, sexual health services, risk communication, and community engagement, as well as primary healthcare, immunization, and other clinical services. Emphasizing a collaborative and coordinated approach, the framework seeks to eliminate human-to-human transmission of mpox while addressing the public health burden, particularly in regions of Africa most affected by Clade I, which carries a higher case fatality rate than Clade II.

In 2022, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) issued the Interim Guidance on Infection Prevention and Control for Patients with Suspected, Probable, or Confirmed Mpox within Healthcare Settings (updated November 2024). This guidance highlights key measures to reduce transmission risks while ensuring safety for both patients and healthcare workers (HCWs).

WHO: Strategic framework for enhancing prevention and control of mpox- 2024-2027

Treatment and Vaccination

There is currently no specific treatment that has been Health Canada- or United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for mpox. Most mild-to-moderate cases resolve with supportive care, including pain management, hydration, and treatment of secondary infections. However, some severe cases may require additional intervention, particularly in immunocompromised individuals or those with ocular, mucosal, or systemic complications.

Antiviral options

- Tecovirimat (TPOXX): An oral antiviral originally approved for smallpox, which has been used off-label for mpox in select high-risk patients. In Canada, it is not currently approved for mpox but can be accessed through provincial and territorial health authorities.

- Brincidofovir: An oral antiviral approved for smallpox that is available in the United States under emergency investigational new drug (IND) access for severe mpox cases.

- Cidofovir: An intravenous antiviral with in vitro activity against orthopoxviruses. It is considered in severe cases where other treatment options are not viable.

- Vaccinia Immune Globulin Intravenous (VIGIV): An immune globulin treatment available in the United States under expanded access IND for severely immunocompromised patients who may not develop an adequate immune response to infection.

Indications for antiviral treatment

Tecovirimat is considered the first-line treatment if antiviral therapy is needed. Patients who may benefit from antiviral treatment include:

- Severely immunocompromised individuals, such as those with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and CD4 counts below 200 cells per cubic millimeter.

- Children or pregnant individuals diagnosed with mpox.

- Patients with severe mpox, including those with extensive mucosal, ocular, or systemic involvement.

In some cases, brincidofovir, cidofovir, or VIGIV may be considered as adjunct or alternative therapies, particularly when:

- There is clinical disease progression while on tecovirimat.

- A patient cannot tolerate tecovirimat or there is concern about antiviral resistance.

Imvamune® vaccine

- Imvamune® is a third-generation, non-replicating vaccine authorized in Canada for protection against smallpox, mpox, and related orthopoxvirus infections.

- Evidence suggests Imvamune® provides protection against multiple mpox virus clades, including Clades Ia, Ib, and IIb.

- In Canada, the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) recommends Imvamune® for:

- Post-exposure vaccination: Individuals who had high-risk exposure to a probable or confirmed case of mpox or exposure in a setting with active transmission.

- Pre-exposure vaccination: Individuals at high risk of exposure, including gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) with multiple sexual partners and certain healthcare workers.

- Dosing schedule: Two doses at least 28 days apart. If given for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), a single-dose regimen may be considered if administered within 14 days of exposure.

Vaccination recommendations for travellers and healthcare workers

- Routine mpox vaccination is not recommended for most travellers.

- However, healthcare workers who are deploying to regions with ongoing Clade I outbreaks should receive two doses of Imvamune® prior to travel.

Vaccine supply and access

- In Canada, Imvamune® is available through PHAC’s National Emergency Strategic Stockpile and is distributed through provincial and territorial health authorities.

Reporting of adverse events following immunization

- Healthcare providers must report adverse events following vaccination to their local public health authorities, which then report to PHAC.

PHAC: Mpox: For health professionals – Management and treatment

CDC: Clinical Treatment of Mpox

What is happening with current outbreaks of mpox?

Mpox continues to circulate globally, with distinct outbreaks occurring due to different viral clades. Clade I mpox remains a significant concern in Central and Eastern Africa, where it has led to sustained human-to-human transmission and travel-associated cases worldwide. Meanwhile, Clade II mpox, responsible for the ongoing global outbreak since 2022, is circulating at low levels in various regions, with occasional localized increases.

Clade I mpox outbreaks: Emerging challenges in Africa and beyond

Clade I mpox, which includes subclades Ia and Ib, is predominantly circulating in Central and Eastern Africa, with sustained transmission occurring in countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Burundi, Kenya, and Rwanda.

- Clade Ia: Most commonly transmitted through zoonotic spillover (contact with infected wild animals) and household transmission. A high proportion of cases occur in children under 15 years. The CFR is higher compared to Clade II.

- Clade Ib: First identified in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, this subclade has primarily spread through sexual contact, including among heterosexual individuals engaged in the sex trade. It has been reported in neighbouring countries and travel-associated cases have been detected in Europe, Asia, and North America. The CFR appears lower than Clade Ia but requires further monitoring.

Countries with documented sustained Clade I transmission include:

- Democratic Republic of the Congo (highest burden, with both Clade Ia and Ib circulating)

- Burundi and Uganda (widespread Clade Ib transmission)

- Kenya and Rwanda (localized outbreaks, potential for undetected transmission)

- Republic of the Congo and Central African Republic (sporadic cases, mostly Clade Ia)

Travel-associated Clade I cases have been reported in Belgium, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Oman, Pakistan, Sweden, Thailand, the United Kingdom, the United States, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

The United States reported its first Clade I mpox cases in November 2024 (California) and January 2025 (Georgia). Both cases were travel-associated, and no secondary infections have been reported. The overall risk to the US population remains low.

Clade II mpox: Ongoing global outbreak at low levels

The global outbreak of Clade IIb mpox, which began in 2022, has led to over 100,000 confirmed cases across 122 countries, including 115 countries where mpox had not been previously reported. While cases peaked in mid-2022, they have since declined significantly, with low-level, ongoing transmission in various regions.

- Clade IIa mpox: Historically found in West Africa, this clade had not been known to spread through human-to-human transmission until 2024, when sustained outbreaks were reported in Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, and Guinea.

- Clade IIb mpox: Responsible for the global outbreak since 2022, affecting populations primarily through sexual transmission, particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM).

As of January 2025, Clade IIb mpox cases continue to be reported in low numbers globally, with clusters occurring in some Western, Northern, and Southern African countries, as well as parts of Europe, the Americas, and Asia.

Key global Clade II trends

- Since 2022, over 102,000 Clade II cases have been confirmed, with 220 deaths reported worldwide.

- In 2024, nearly 9,000 cases of Clade II mpox were reported globally, with continued localized outbreaks.

- Recent outbreaks occurred in South Africa and Côte d’Ivoire in late summer 2024, reflecting potential new hotspots.

- Australia experienced an unprecedented rise in cases in 2024, though transmission has declined in recent months.

Mpox in Canada: Current situation

Mpox cases in Canada remain low, with Clade IIb being the dominant strain. As of November 29, 2024, the epidemiological pattern remains stable, with no deaths reported.

Key trends in Canada:

- Localized transmission continues, mostly among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM).

- Most cases are acquired in Canada, suggesting ongoing domestic transmission rather than importation.

- Hospitalizations are rare, with no recorded deaths since the start of the outbreak.

- Recent increases in cases in some regions may be linked to increased travel and mass gatherings during summer and fall.

PHAC continues to collaborate with provinces and territories to monitor outbreaks, study transmission patterns, and implement timely public health interventions.

CDC: Ongoing Clade II Mpox Global Outbreak

WHO: Multi-country outbreak of mpox, External situation report #46 – 28 January 2025

What is the current risk for Canadians from mpox?

The risk of mpox to the general population in Canada remains low, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). While new cases continue to be detected, the overall number of infections is significantly lower than the peak observed during the summer 2022 outbreak. Ongoing public health surveillance suggests that localized transmission persists, primarily within high-risk groups, but there have been no reported deaths and hospitalizations remain rare.

Mpox clades circulating in Canada – 2 major clades

- Clade I (Central African clade) – Divided into subclades Ia and Ib, this clade is associated with more severe disease and higher case fatality rates. It is not widely circulating in Canada but has been detected in travel-associated cases.

- Clade II (West African clade) – Divided into subclades IIa and IIb, this clade is associated with milder disease. The majority of mpox cases in Canada have been caused by Clade IIb, which is the same strain responsible for the 2022 global outbreak.

Mpox cases continue to be reported in Canada, but patterns of transmission remain stable. The following trends have been observed:

- Most cases occur among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM).

- Most infections are acquired within Canada, suggesting ongoing localized transmission rather than importation from other countries.

- Hospitalizations are rare, and no deaths have been reported.

- A slight increase in cases in certain regions has been observed, likely due to increased travel and mass gathering events over the summer and fall.

- Despite this recent increase, case counts remain far below the peak levels seen in 2022.

PHAC, in collaboration with provincial and territorial health authorities, continues to monitor the situation closely and implement measures to prevent further spread. Current priorities include:

- Ongoing surveillance to detect new cases quickly.

- Assessing new scientific evidence to refine public health recommendations.

- Encouraging vaccination among high-risk populations to prevent transmission.

Travel advisory

Travellers should be aware of ongoing mpox outbreaks, particularly those caused by clade I, which is currently spreading in several Central and East African countries, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, Republic of Congo, Burundi, Rwanda, Kenya, and Uganda. While clade I mpox is historically endemic to these regions, the current outbreaks are larger than expected, and new cases have been detected outside of Central Africa for the first time. Travel-related cases have also been reported in Europe, Asia, and North America. Due to the increasing spread, WHO declared the situation a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on August 14, 2024. PHAC continues to monitor these developments and coordinate with international and domestic health partners to assess risks and implement preventive measures.

To reduce the risk of infection while traveling, individuals should avoid close physical contact with individuals who have mpox, including sexual contact, prolonged face-to-face exposure, and sharing personal items. Travellers should also practice good hand hygiene, avoid handling or consuming wild animals, and consider vaccination if eligible, particularly those at high risk of exposure. While routine vaccination is not recommended for most travellers, healthcare professionals deployed to support clade I outbreaks in affected regions should receive two doses of the Imvamune® vaccine at least 28 days apart before traveling. Those who develop mpox symptoms during travel or upon return to Canada should immediately isolate, seek medical advice, and notify public health authorities if necessary. Monitoring for symptoms for 21 days post-travel is also advised, as mpox can have an incubation period of up to three weeks.

PHAC: Mpox: Advice for travellers (December 3, 2024)

What measures should be taken for a suspected mpox case or contact?

Public health authorities should follow provincial, territorial, and local reporting requirements when a suspected mpox case is identified. National case definitions are in place to ensure consistency in case identification. PHAC provides a case report form to facilitate standardized reporting and surveillance.

Case management and isolation guidelines

All suspected, probable, and confirmed mpox cases should isolate until they are no longer contagious, which typically lasts 2 to 4 weeks but may extend longer. Isolation measures include:

- Staying at home and avoiding contact with others.

- Receiving essential supplies (food, medications) through delivery services or designated caregivers.

- Not traveling to other regions or countries while contagious.

- Avoiding elective medical visits and donating blood or bodily fluids.

- Minimizing contact with others by staying in a separate room and using a separate bathroom, if possible.

- For individuals in congregate settings (e.g., shelters, correctional facilities), alternate accommodations may be necessary to ensure proper isolation.

Public health monitoring and support

- Active monitoring should be conducted for suspected or confirmed cases to track symptom progression and ensure adherence to isolation guidelines.

- Healthcare professionals should be notified of worsening symptoms, with guidance provided on when and how to seek medical care.

- Individuals with clade I mpox infections should be closely monitored for more severe disease progression.

If the case lives with others, additional precautions should be taken:

- Isolate in a separate room and use a separate bathroom if available.

- Cover all lesions with clothing or bandages.

- Wear a medical mask when in shared spaces.

- Avoid sharing household items such as towels, utensils, clothing, razors, or bedding.

- Disinfect frequently touched surfaces and launder contaminated items immediately.

Although mpox is not currently spreading among animals in Canada, human-to-animal transmission is possible. To prevent this:

- Avoid close contact with pets, livestock, and wildlife.

- Assign another household member to care for pets.

- Wear gloves and a mask when handling pet supplies if direct contact is unavoidable.

- Monitor pets for symptoms if they were exposed to an infected individual.

Orthopoxviruses can remain stable on surfaces for prolonged periods, making thorough cleaning essential:

- Frequently clean high-touch surfaces (e.g., doorknobs, countertops, bathroom fixtures) with Health Canada-approved disinfectants.

- Handle and wash laundry carefully, avoiding shaking contaminated items to prevent airborne particles.

- Dispose of waste properly, ensuring pets and wildlife cannot access contaminated materials.

Public health authorities should conduct contact tracing for confirmed and probable cases. Contacts should be categorized by risk level:

- High-risk exposure: Prolonged skin-to-skin or mucosal contact with an infected individual or their bodily fluids, including sexual partners and household members.

- Intermediate-risk exposure: Limited close contact without proper personal protective equipment (PPE) (e.g., sitting next to an infected individual for an extended period).

- Low-risk exposure: Brief interactions with an infected individual or consistent use of proper PPE during exposure.

Public health measures for contacts

For 21 days post-exposure, all contacts should:

- Monitor for symptoms and notify public health authorities if any develop.

- Practice hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette.

- Avoid donating blood or bodily fluids.

- Use barrier protection (e.g., condoms, dental dams) during sexual activity.

- Be aware of travel restrictions, as symptom onset could require isolation in another location.

High-risk contacts should take additional precautions:

- Wear a medical mask in shared spaces, including at home.

- Avoid sexual contact until the incubation period has passed.

- Limit interactions with vulnerable populations (e.g., immunocompromised individuals, pregnant individuals, young children).

Post-recovery precautions

Live mpox virus has been detected in semen and other bodily fluids for weeks post-recovery. While transmission through genital fluids is not confirmed, WHO recommends condom use for 12 weeks after infection as a precaution.

The Public Health Agency of Canada recommends consulting the Interim guidance on infection prevention and control for patients with suspected, probable or confirmed mpox within healthcare settings for more information.