Are you looking for the PHAC guidance document for practitioners?

NCCID Disease Debriefs provide Canadian public health practitioners and clinicians with up-to-date reviews of essential information on prominent infectious diseases for Canadian public health practice. While not a formal literature review, information is gathered from key sources including the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the World Health Organization (WHO), and peer reviewed literature.

This disease debrief has been prepared by Signy Baragar. Questions, comments and suggestions regarding this debrief are most welcome and can be sent to nccid@manitoba.ca.

What are Disease Debriefs? To find out more about how information is collected, see our page dedicated to the Disease Debriefs.

UPDATED: December 11, 2025

What are important characteristics of MERS-CoV?

CAUSE

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a viral respiratory caused by the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). It was first identified in Saudi Arabia in 2012 and has since spread to several other countries.

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses common throughout the world. They can infect humans and animals. In humans, coronaviruses usually cause mild to moderate upper-respiratory illness, such as the common cold. However, coronaviruses can also cause more severe illnesses including the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The clinical manifestation of MERS-CoV infection ranges from asymptomatic or mild respiratory symptoms to more severe pneumonia-like symptoms.

Common symptoms include:

- Fever

- Cough

- Shortness of breath

Pneumonia is common, but not always present. Some individuals may also experience gastrointestinal issues like vomiting or diarrhea. People at higher risk for more serious illness include those who are older, immunocompromised, or living with chronic health conditions.

Symptomatic cases are most common. Of the 2,800 cases reported worldwide between 2012 and 2025, 2,200 were symptomatic and 174 were asymptomatic, while symptom status was not reported for 237 cases.

SEVERITY

Approximately 35% of MERS-Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection cases are fatal. Most cases have had underlying medical conditions and weak immune systems.

INCUBATION PERIOD

The incubation period for MERS-CoV is largely unknown. It has been reported as a prolonged incubation period with analyses suggesting 5-6 days before symptoms first appear. However, symptoms may take as long as 14 days to appear after exposure.

RESERVOIR AND TRANSMISSION

MERS-CoV is a zoonotic virus that is transmitted from infected dromedary camels to humans. It is believed that the virus originated in bats and was transmitted to camels sometime before 1992.

Although recent studies point to the role of camels as a primary source of MERS-CoV infection in humans through direct or indirect contact with infected camels or camel-related products (e.g. raw camel milk), the exact route of camel to human transmission is not fully understood.

Human-to-human infections

No community-wide transmission has been observed to date. However, human-to-human transmission has been observed in health care settings, clusters of close contacts, and within households of affected countries.

- PHAC – Summary of Assessment of Public Health Risk to Canada Associated with MERS-CoV

- PHAC – MERS-CoV – For Health Professionals

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS

Laboratory confirmation is obtained by detection of the virus using (a) MERS-CoV specific nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) with up to two separate targets and/or sequencing; or (b) virus isolation in tissue culture; or (c) serology on serum tested in a WHO collaborating center with established testing methods.

Requests for MERS-CoV testing should be directed to the appropriate Provincial Public Health Laboratory (PPHL). Some provincial public health and hospital laboratories can perform initial MERS-CoV screening, however, these cases should be considered probable pending confirmation of diagnosis from the Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) before being considered conclusive. Laboratory testing should be conducted in accordance with the Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network’s Protocol for Microbiological Investigations of Severe Acute Respiratory Infections (SARI).

- PHAC – National Surveillance Guidelines for Human Infection with MERS-CoV

- PHAC – Protocol for Microbiological Investigations of Severe Acute Respiratory Infections (SARI)

- PHAC – Infection Prevention and Control Guidance for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Acute Care Settings

- PHAC – MERS-CoV – For Health Professionals

VACCINATION

There is currently no licensed vaccine approved for human use, although several candidate MERS-CoV vaccines are underway. For example, three MERS-CoV vaccine candidates (MVA-MERS-S, GLS-5300 DNA, and ChAdOx1) have undergone phase 1 and 1b clinical trials to evaluate their safety and immunogenicity. A full list of candidate vaccines and their stage of clinical evaluation or regulatory status, from 2019 to 2020, are available at WHO – Classes of candidate vaccines against MERS-CoV.PDF .

- Shen et al. (2024) – DNA vaccine prime and replicating vaccinia vaccine boost induce robust humoral and cellular immune responses against MERS-CoV in mice – ScienceDirect

- PHAC – Summary of Assessment of Public Health Risk to Canada Associated with MERS-CoV

TREATMENT

There is currently no specific treatment for MERS. Treatment is supportive and based on the patient’s clinical condition. For health care providers managing patients in the intenstive care unit setting who have a severe acute respiratory infection, such as MERS, please refer to the Guidance for the Management of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection in the Intensive Care Unit prepared by the Canadian Critical Care Society.

What is happening with current outbreaks of MERS-CoV?

EPIDEMIOLOGY

No MERS-CoV cases have been reported in Canada.

All cases of MERS-CoV have been linked to countries in the Middle East, with the majority of cases (approximately 80%) reported from Saudi Arabia. This is largely as a result of contact with infected dromedary camels or contact with infected individuals in health care facilities. Since MERS-CoV was identified in April 2012, 2,640 cases of MERS-CoV and 958 deaths have been reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) from 27 regions, of which, 2,200 cases were reported from Saudi Arabia (Table 1).

Most cases identified outside the Middle East have occurred in people who were likely exposed while in the Middle East and then travelled abroad. Only a small number of outbreaks have been reported outside the Middle East to date (Table 1).

Table 1. Cumulative number of MERS-CoV cases reported to WHO across regions, 2012-2025

| Regions | Number of MERS-CoV cases |

| Saudi Arabia | 2,200 |

| Republic of Korea | 186 |

| United Arab Emirates | 94 |

| Jordan | 28 |

| Qatar | 28 |

| Oman | 26 |

| Iran (Islamic Republic of) | 6 |

| United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland | 5 |

| Kuwait | 4 |

| Germany | 3 |

| Thailand | 3 |

| Tunisia | 3 |

| Algeria | 2 |

| Austria | 2 |

| France | 2 |

| Lebanon | 2 |

| Malaysia | 2 |

| The Netherlands | 2 |

| Philippines | 2 |

| United States of America | 2 |

| Bahrain | 1 |

| China | 1 |

| Egypt | 1 |

| Greece | 1 |

| Italy | 1 |

| Türkiye | 1 |

| Yemen | 1 |

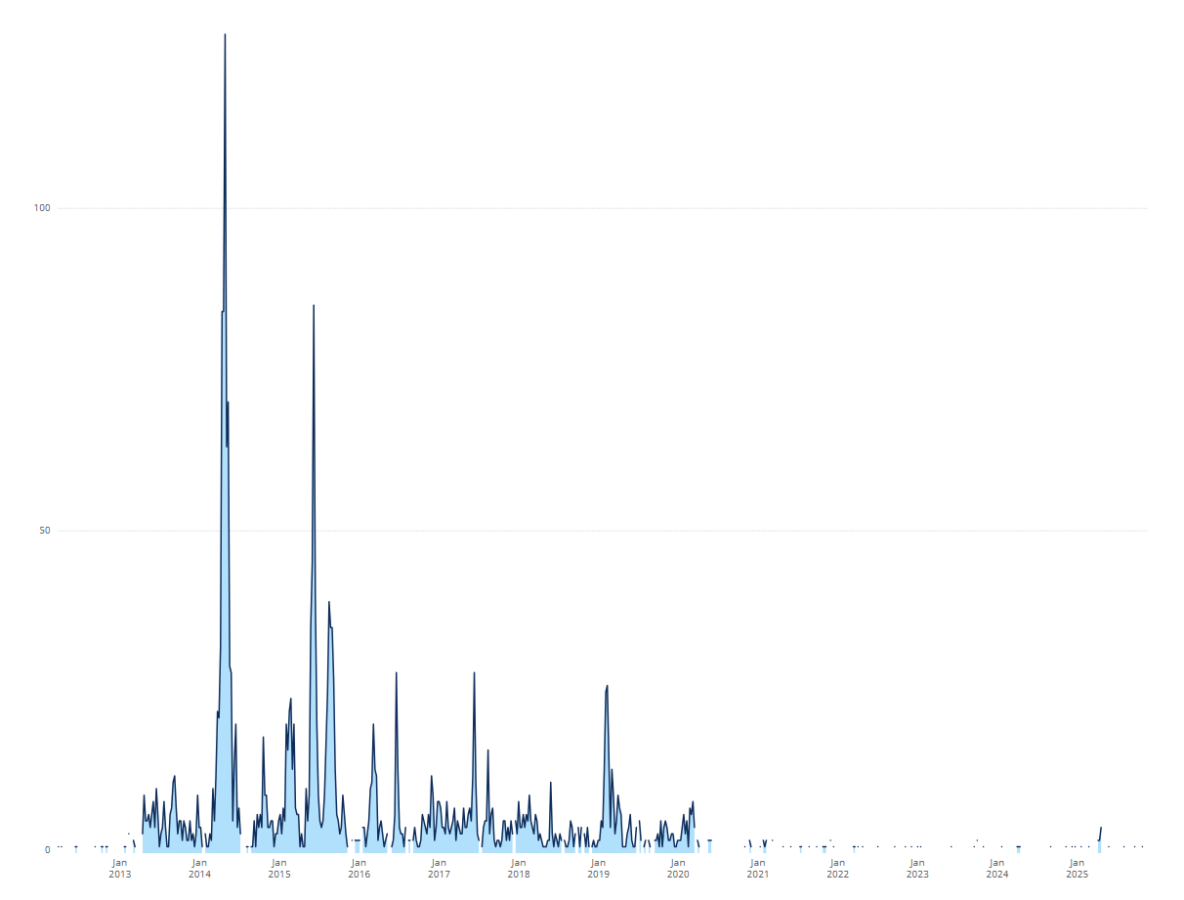

The highest number of MERS-CoV cases reported to the WHO in a single epidemiological week occurred in Week 27 (April) 2014, with 127 cases, predominantly from the Eastern Mediterranean region. Figure 1 shows the distribution of cases reported to the WHO since 2012.

Figure 1. Cumulative number of MERS-CoV cases reported to WHO, 2012-2025

Outside the Middle East, the largest outbreak occurred in the Republic of Korea, beginning in May, 2015. The outbreak resulting from a single case who travelled to four countries in the Middle East and, upon returning to South Korea, spread the virus to close relatives, health-care workers and patients, resulting in a total of 186 infected cases and 38 patient deaths.

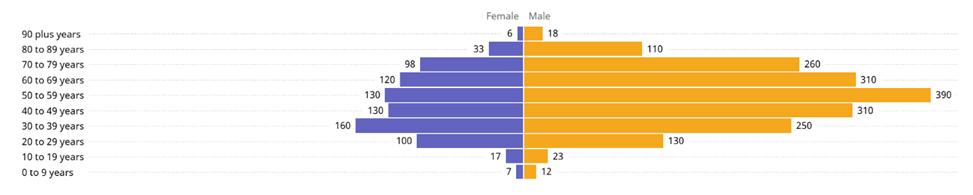

The majority of cases occur in males and in individuals between the ages of 18 and 59 years. The distribution of cases across age and sex are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Distribution of MERS-CoV cases since 2012 by age and sex

- PHAC – Summary of Assessment of Public Health Risk to Canada Associated with MERS-CoV

- WHO – Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)

- WHO – MERS-CoV Dashboard

What is the current risk for Canadians from MERS-CoV?

The risk of contracting MERS-CoV infection in Canada is low. To date, no cases of MERS-CoV have ever been reported in Canada. Globally, most cases have occurred among people living in or travelling to the Middle East, or among individuals who had contact with a sick person who had recently travelled to the region.

TRAVEL RECOMMENDATIONS

There are no travel health notices related to MERS-CoV for Canadian travellers. However, PHAC encourages travellers to always check the Travel Advice and Advisories (TAA) page twice for their destination: once when they are planning their trip, and again shortly before they leave. The TAA page offers country-specific travel information, including health risks, safety, local laws and customs.

At this time, the WHO does not advise special screening for MERS-CoV at points of entry, nor does it currently recommend the application of any travel or trade restrictions.

- PHAC – Travel health notices

- WHO – Disease Outbreak News: Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus_Feb 16, 2024

What measures should be taken for a suspected MERS-CoV case or contact?

CASE AND CONTACT MANAGEMENT

PHAC has developed guidance for public health authorities on containing and managing MERS-CoV cases in Canada. Case management should focus on symptomatic treatment, actively monitoring patients on a daily basis until infection is ruled out, and providing patients, as required, with guidance on home care, where and when to go for medical assessment, how to report travel history or contact history, and prevention of transmission.

CASE DEFINITIONS

The following case definitions are presented as published by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). These definitions are provided for reference only and do not replace clinical or public health judgment in individual patient management, nor are they intended for infection prevention and control triage purposes.

Confirmed Case:

A person with laboratory confirmation of MERS-CoV infection at Canada’s NML. The NML can confirm detection of the virus using MERS-CoV specific nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) and/or sequencing and though virus isolation in tissue culture.

Probable Case:

A person epidemiologically-linked through close contacta to a laboratory-confirmed case and meeting illness criteriab but in whom laboratory diagnosis of MERS-CoV is not available or negative (if specimen quality or timing is suspect).

Note: Laboratory confirmation not available: due to (a) no possibility of acquiring samples for laboratory testing for MERS-CoV either because the patient or samples are not available; or (b) laboratory diagnosis negative (i.e. negative MERS-CoV result but specimen quality or timing is suspect).

OR

A person meeting exposurec and illnessb criteria and in whom laboratory screening test for MERS-CoV was positive but not confirmed by the NML.

Note: A positive screening test for MERS-CoV should meet one of the following conditions: (1) a positive PCR result for at least two different specific targets on the MERS-CoV genome; OR (2) one positive PCR result for a specific target on the MERS-CoV genome and MERS-CoV sequence confirmation from a separate viral genomic target. Laboratory findings may take up to 7 days from specimen submission. See additional notes under PUI.

Person Under investigation (PUI):

A person meeting exposurec and illnessb criteria.

Note: The surveillance mechanisms and systems for identifying a PUI may vary by jurisdiction according to perceived risk, resources, supporting structures and other context.

Note: Limited data suggests that MERS-CoV can present as a co-infection with other viral pathogens. The identification of one causative agent should not exclude MERS-CoV where the index of suspicion may be high.

—

aA close contact is defined as a person who provided care for the patient, including health care workers (except those wearing appropriate PPE), family members or other caregivers, or who had other similarly close physical contact OR who stayed at the same place (e.g. lived with or otherwise had close prolonged contact within two metres) as a probable or confirmed case while the case was ill.

bIllness criteria: Illness onset is defined by the earliest start of respiratory symptoms associated with the current episode. Focus is on the detection of severe acute respiratory illness (SARI) defined primarily by respiratory symptoms, i.e. fever (over 38 degrees Celsius) AND new onset of (or exacerbation of chronic) cough or breathing difficulty as well as clinical, radiological or histo-pathological evidence of pulmonary parenchymal disease (e.g. pneumonia, pneumonitis, or Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome [ARDS]), typically associated with the need for hospitalization, intensive care unit monitoring and/or other severity marker (such as death).

Many infectious diseases present with a spectrum of illness, including mild or asymptomatic infection. Atypical MERS-CoV presentation with absent respiratory symptoms has been documented in the presence of comorbidity, notably immuno-suppression. Therefore, clinician and public health judgment should be used in assessing patients with milder or atypical presentations, where, based on contact, comorbidity or cluster history, the index of suspicion may be raised. Additional information can be found in the Interim Guidance For Containment When Imported Cases With Limited Human-To-Human Transmission Are Suspected/Confirmed In Canada.

Clinician discretion, epidemiologic context and local feasibility should be taken into account in discussion with local/provincial health authorities.

c Exposure criteria: Links within 14 daysa prior to illness2 onset to affected areasb (i.e. residence, travel history) OR close contactc with a confirmed or probable case of MERS-CoV or a traveller or resident with any acute respiratory illness returning from an affected areab. Factors that raise the index of suspicion should also be consideredd.

- Incubation period for MERS-CoV is still largely unknown but has been reported as prolonged in one documented instance of person-to-person nosocomial transmission (9- 14 days). SARS-CoV also demonstrated a prolonged incubation period (median 4-5 days; range 2-10 days) compared to other human coronavirus infections (average 2 days; typical range 12 hours to 5 days). Allowing for inherent variability and recall error and to establish consistency with other emerging respiratory virus monitoring, exposure history based on the prior 14 days is a reasonable and safe approximation.

- Affected areas: As affected areas are subject to change, consult the Summary of Assessment of Public Health Risk to Canada Associated with MERS-CoV for the most up -to -date information. A close contact is defined as a person who provided care for the patient, including health care workers (except those wearing appropriate PPE), family members or other caregivers, or who had other similarly close physical contact OR who stayed at the same place (e.g. lived with or otherwise had close prolonged contact within two metres) as a probable or confirmed case while the case was ill.

- Factors that raise the index of suspicion include having a history of being in a health care facility (as a patient, worker or visitor) OR having contact with camel or camel products (e.g. raw milk or meat, secretions or excretions, including urine), in an affected area within 14 days of illness onset.

IDENTIFYING AND REPORTING

Health professionals are encouraged to obtain a detailed travel and exposure history from patients with MERS-like symptoms, including travel or exposures during the 14 days prior to illness onset. This should include: any epidemiological links to MERS-affected areas; close contact with confirmed or probable MERS-CoV cases; or contact with a traveller or resident returning from a MERS-affected area who has an acute respiratory illness. For patients who have been in a MERS-affected area within 14 days of illness onset, a history of being in a health care facility or contact with camels or camel products should raise the index of suspicion for MERS-CoV infection.

Suspected, probable, and confirmed cases should be reported by health care professionals in accordance with local, provincial, or territorial reporting requirements.

Health professionals are advised to review the following guidance for detecting, tracking, testing, diagnosing, analyzing, and reporting MERS-CoV in Canada:

- National Surveillance Guidelines for Human Infection with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV)

- Protocol for microbiological investigations of severe acute respiratory infections (SARI)

The case report form, including instructions for reporting potential MERS-CoV cases, is available at:

PREVENTION AND CONTROL

In the event that a MERS-CoV case is identified within a Canadian jurisdiction, public health authorities working at federal/provincial/territorial levels should refer to the guidance document, Public Health Management of Human Illness Associated with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV): Interim Guidance for Containment When Imported Cases Are Suspected/Confirmed in Canada. The guidance document offers recommendations for containing MERS-CoV cases in the home setting and should be read in conjunction with relevant P/T and local legislation, regulations, and policies.

Health professionals are encouraged to consult the Agency’s Infection Prevention and Control Guidance for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Acute Care Settings for detailed recommendations on identifying, managing, and containing MERS-CoV in acute health care settings, including triage, patient placement, PPE use, environmental cleaning, and monitoring of exposed patients and staff.

To access a detailed form and instructions for reporting potential MERS-CoV cases, please refer to Emerging respiratory pathogens and severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) – Case report form.

Individual-level Prevention Measures

MERS-CoV, like other coronaviruses, is believed to spread from an infected person’s respiratory secretions, such as those released during through coughing or sneezing, therefore, respiratory hygiene is essential. Individuals with symptoms of acute respiratory infection are encouraged to use tissues or wear a mask when coughing or sneezing. Coughing into the sleeve may be used only when tissues or masks are not available, as it is considered a less effective alternative.