Updated April 2, 2025

NCCID Disease Debriefs provide Canadian public health practitioners and clinicians with up-to-date information on prominent infectious diseases for Canadian public health practice. While not a formal literature review, information is gathered from key sources including the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO) and peer reviewed literature.

Questions, comments and suggestions regarding this debrief are most welcome and can be sent to nccid@manitoba.ca

Questions Addressed in this debrief:

- What are important characteristics of measles?

- What is happening with current outbreaks of measles?

- What is the current risk for Canadians from measles?

- What measures should be taken for a suspected measles case or contact?

What are important characteristics of Measles?

Cause

Measles is a single stranded, enveloped RNA virus belonging to the Morbillivirus genus in the Paramyxoviridae family. The virus can cause a measles infection which starts in the respiratory epithelium of the nasopharynx. Measles is highly contagious.

Sign and Symptoms

Symptoms begin 7 to 21 days after becoming infected with the measles virus and include a high fever (approximately 38.3°C), cough, runny nose, conjunctivitis (red, watery eyes), Koplik spots (tiny, white dots on the inside of the mouth), and a rash all over the body. The rash is the most visible symptom and typically begins on the face and upper neck before spreading to the hands and feet. The rash usually lasts for 5 to 6 days before disappearing.

Severity and Complications:

Complications from measles commonly include ear infections and diarrhea. Some people, however, will develop severe complications which can lead to death. Severe complications can include:

- Pneumonia

- Respiratory failure

- Pregnancy-related complications (e.g., miscarriages, premature labour, low birth weight infants)

- Encephalitis (swelling of the brain)

When encephalitis occurs, long-term complications can include blindness, deafness, and intellectual disability.

Another long-term complication of measles includes a neurological condition called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). SSPE is a rare yet fatal disease that generally develops 7 to 10 years after a person has measles, even if a person appears to have fully recovered from measles. The risk of developing SSPE is higher if measles is acquired before the age of two.

Epidemiology

General:

Measles is prevalent throughout the world, especially in parts of Africa and Asia, and remains a leading cause of vaccine-preventable deaths in children worldwide. The majority (more than 95%) of measles deaths occur in countries with low per capita incomes or weakened health infrastructures that cannot immunize all children with the measles vaccine.

Between 2020 and 2022, over 61 million doses of measles vaccines were postponed or missed due to COVID-19-related delays. Vaccination coverage for measles decreased from 84% in 2020 to 81% in 2021 – the lowest vaccination coverage since 2008. By 2022, vaccination coverage increased to 83%.

Following an overall decline in measles vaccination coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic, the worldwide estimate of measles cases increased by 18% and measles deaths increased by 43% between 2021-2022 – most of which occurred among unvaccinated children. In 2023, the worldwide estimate of measles cases decreased by 20% (10.3 million cases), and measles deaths decreased by 8% (107 500 deaths). By 2024, approximately 1 million suspected and confirmed cases were reported to the WHO. However, the global estimate of measles cases is likely much greater.

Table 1. Reported measles cases by WHO region, Canada, and the United States, 2018-2023

| Location | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Africa | 125,426 | 618,595 | 115,369 | 88,789 | 97,185 | 424 433 |

| Europe | 89,148 | 106,130 | 10,945 | 99 | 825 | 55 589 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 64,764 | 18,458 | 6,769 | 26,089 | 56,401 | 92 761 |

| South-East Asia | 34,741 | 29,389 | 9,389 | 6,448 | 49,201 | 85 368 |

| Western Pacific | 29,503 | 78,479 | 6,605 | 1,067 | 1,442 | 5630 |

| Americas | 16,714 | 21,971 | 9,996 | 682 | 47 | 14 |

| Canada | 28 | 113 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 12 |

| United States of America | 375 | N/A | 1,275 | 14 | N/A | N/A |

Note. Data reproduced from the World Health Organization’s Global Health Observatory (GHO)’s measles indicator as of 13 July 2023. Data for the United States in 2019, 2022 and 2023 are unavailable.

- CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR)–Progress Towards Measles Elimination–Worldwide, 2000-2022

- CDC–Global Measles Outbreaks

- WHO News Release–Global measles threat continues to grow as another year passes with millions of children unvaccinated–November 16, 2023

- World Health Organization’s Global Health Observatory (GHO)-Measles Indicator

- The Lancet- Worrying global decline in measles immunization- January 2022

- WHO – Measles Fact Sheet

Canada:

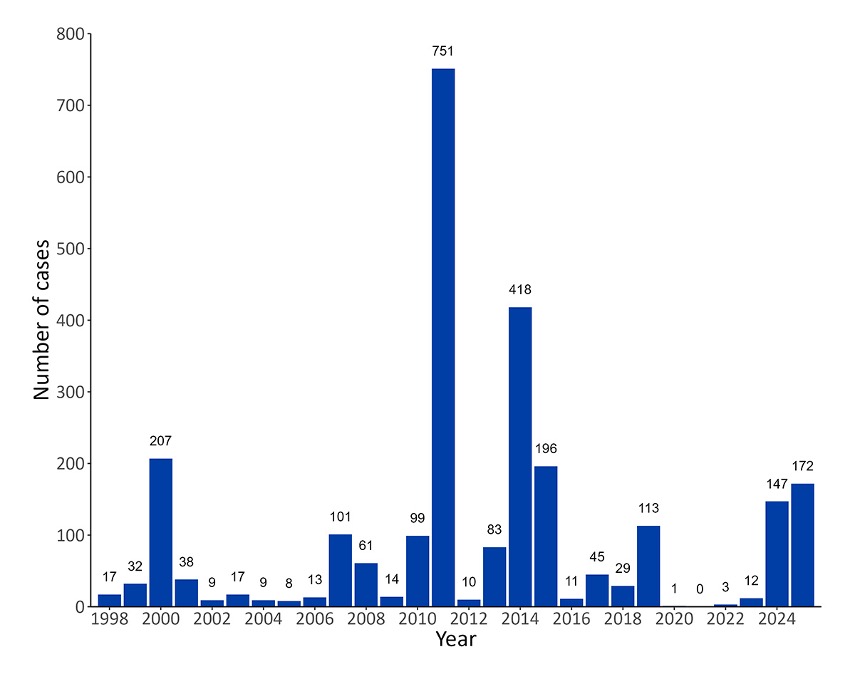

Measles has decreased significantly in Canada over time. Prior to the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963, between 10,000 and 90,000 people were infected with measles in Canada each year. Fortunately, measles cases drastically declined following the introduction of the vaccine from an average of 9,863 annual cases between 1969 and 1983 to to zero cases in 2021 (Figure 1). By 1998, Canada achieved measles elimination status (the absence of constantly present transmission for greater than 12 months).

Most recently, In Canada, 224 measles cases (173 confirmed, 51 probable) and have been reported in 2025 as of March 1.

Figure 1. Number of measles cases reported in Canada by year of rash onset since measles elimination, 1998 – March 1, 2025

Note. Figure reproduced from Measles and Rubella Weekly Monitoring Report: Week 9 (February 23 to March 1, 2025)

- Government of Canada-Measles: For health professionals

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC)-Guidelines for measles outbreak in Canada (October, 2013)

- Government of Canada-Measles & Rubella Weekly Monitoring Report-Week 9: February 23 – March 1, 2025

United States:

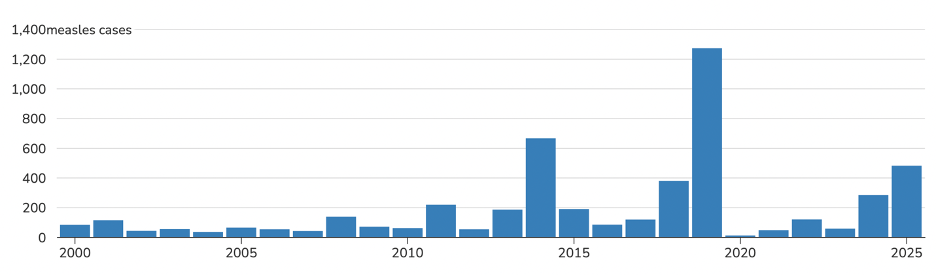

Measles became nationally notifiable in the United Stated in 1912 with approximately 6,000 annual deaths, on average, within the first decade of national reporting. Prior to the measles vaccine becoming available in 1963, between 3 to 4 million people were infected with measles in the United States each year, with 300 to 400 annual deaths. By 2000, the United States achieved measles elimination status.

The annual number of measles has varied in the United States in the past decade, peaking in 2019 at 1,274 cases. Between September 2018 and September 2019, there were 26 outbreaks recorded in the United States, with most cases reported in New York City and the rest of New York State. As of March 27, 2025, a total of 483 confirmed measles cases were reported.

Figure 2. Number of measles cases in the United States, 2000-2025

Note. Reproduced from CDC–Measles (Rubeola)-Cases and Outbreaks. Data as of March 17, 2025. The 2025 case count is preliminary and subject to change.

- CDC-History of Measles

- CDC MMWR-National Update on Measles Cases and Outbreaks-January 1-October 1, 2019

- CDC-Measles-Cases and Outbreaks

Incubation

Measles incubation is approximately 10 days but can range between 7-18 days. The rash can appear between 14-21 days after exposure.

Reservoir

Humans are the only reservoir for measles.

Transmission

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases in the world. It is transmitted when an infected person coughs, sneezes, breathes, or talks. As an airborne disease, the virus can remain in the air or on a surface for up to two hours after an infected person leaves an area. If another person enters the contaminated air or touches an infected surface, they can become infected. Measles can be transmitted to others from up to four days before a rash develops to four days after the rash disappears.

The secondary attack rate (SAR), or probability that measles infection spreads among susceptible people within a specific group (e.g., close contacts), is high at 90%. In other words, if one person has measles, up to 9 out of 10 close contacts of that person who are not immune will also become infected.

The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles indicates its contagiousness and transmissibility and is estimated at 12-18. This means that each person infected with measles will, on average, infect 12 to 18 other people within a susceptible population.

- Government of Canada-Measles for health professionals

- CDC-Measles (Rubeola)-Transmission

- WHO-Measles

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC): Factsheet about measles

Laboratory Diagnosis

Provinces and territories in Canada are responsible for immediately collecting specimens for serology testing and virus detection, as well as ensuring that the testing turnaround time for reporting results is no more than 72 hours.

Laboratory confirmation of measles involves the immediate collection of specimens for serology and virus detection. As soon as possible, specimens should be collected by nasopharyngeal (preferred) or throat swab and no later than four days after the onset of rash. Specimens may also be collected in urine within seven days from the rash onset. For immunoglobulin G (IgG) serology, clinicians should collect one sample within seven days of rash onset and a second sample between 10 to 30 days after the first sample collection. For immunoglobulin M (IgM) serology, it is important to note that a result may be falsely negative if the specimen collection is performed three days prior to or 28 days after rash onset.

Acute measles infection is associated with a positive measles IgM result when a rash is present and if there is a history of exposure to measles (either through travel to an endemic area or through close contact with a confirmed case). A test may be falsely positive if a patient has a positive measles IgM test without a history of exposure to measles or if they received the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine within six weeks before rash onset.

To detect measles-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies, the gold standard test is the plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT). An enzyme immunoassay (EIA) can also be used to indicate immunity to measles, although it does not always correlate with the protective neutralizing antibodies measured by the PRNT. The protective level of measles IgG is estimated to be between 120 and 200 mIU.

For diagnosing measles, the most reliable test is the reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay given it is performed as soon as possible after rash onset. However, the sensitivity of RT-PCR can be influenced by certain factors including: prior vaccination history, timing of specimen collection, specimen integrity, and specimen storage conditions. Another test with high specificity is the isolation of measles virus in culture when confirmed by RT-PCR or immunofluorescence. Virus isolation in culture is less sensitive than RT-PCR and very dependent on the integrity and timely collection of specimens.

The National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) performs genotyping for Canada to link cases and outbreaks. Genotyping is also used to distinguish the wild type measles infection from a post-vaccine rash. The same type of specimens that were used for the RT-PCR must be used for genotyping.

For full details on laboratory testing of measles, please consult the PHAC’s Guidelines for measles outbreak in Canada: Laboratory Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Measles

Prevention and Control

As a result of successful and routine measles vaccination programs, Canada achieved elimination status for measles in 1998. To sustain Canada’s measles elimination status, it is vital to maintain high vaccine coverage in the country. PHAC recommends a combined measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (MMRV) vaccine or a combined measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine to all children after the first birthday (between 12- 15 months of age). A second dose is administered at either 18 months or any time before school entry. The MMRV is only authorized for children between 12 months and 13 years of age. Health care providers are encouraged to promote the importance of updating routine measles vaccinations with their patients. For more information, please refer to the Government of Canada’s travel health notice for the current status of global measles.

The MMR vaccine is a cost-effective preventative strategy that has been used for approximately 60 years, costing less than CAD$1.35 (US$1.14) per child. In 2022, 74% of children worldwide received both doses of the measles vaccine, and 83% received one dose of the measles vaccine by their second birthday.

Measles cases should be reported to PHAC as soon as possible after a case is identified. In accordance with provincial, territorial, and territorial protocols, announcements to the public of measles outbreaks should only occur after an alert has been sent to PHAC.

- Government of Canada-Measles: For healthcare professionals-Prevention and control

- World Health Organization-Immunization coverage

- Pan American Health Organization-Measles-Prevention

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC)-Guidelines for measles outbreak in Canada (October, 2013)

Treatment

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) should be offered to people who are exposed to measles and who do not have immunity against measles. Either the MMR vaccine can be administered within 72 hours of the initial exposure to measles or immunoglobin (IG) within six days of exposure to potentially provide protection, however, the MMR vaccine and IG should not be administered simultaneously.

No specific antiviral treatments exist for measles infection. Medical care, such as rehydration, is provided for symptomatic relief and to manage complications of measles.

Vitamin A deficiency has been linked to measles complications, such as eye damage and blindness, and delayed recoveries. As such, healthcare providers should provide two doses of vitamin A supplements to patients, given 24 hours apart.

What is happening with current outbreaks of measles?

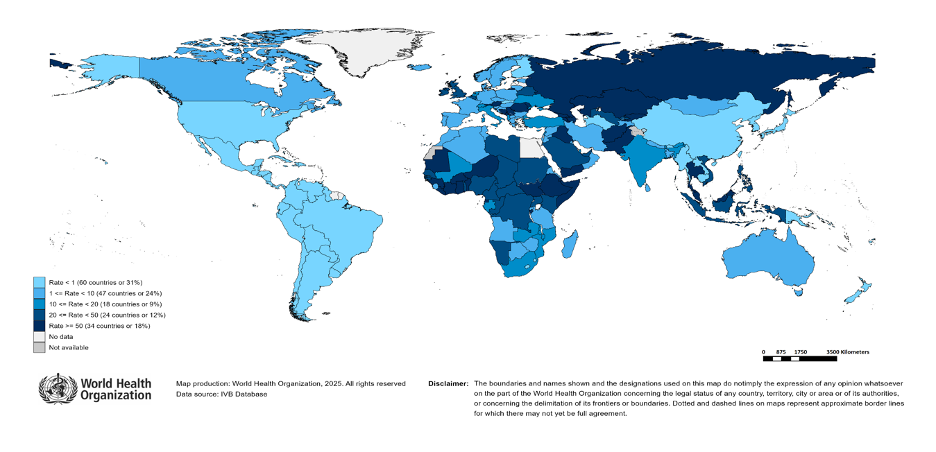

Measles activity has been increasing worldwide and is largely attributed to an increase in un- or under vaccinated individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the United Nations Press Briefing on February 20, 2024, the global number of measles cases had increased 79%, with over 300,000 cases reported in 2023. In 2024, the number of annual cases rose to over 350,000 worldwide. Most cases have been reported in Yemen, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, India, and Ethiopia. The number of measles outbreaks increased near the end of 2024 and is suspected to continue to increase in 2025 due to low vaccination coverage.

Table 2. Countries with the highest incidence of measles cases per 1,000,000 during 2024

| Country | Cases | Incidence per 1 million population |

| Kyrgyzstan | 12,940 | 1,800.72 |

| Romania | 27,314 | 1,436.44 |

| Kazakhstan | 18,805 | 913.19 |

| Azerbaijan | 8588 | 830.64 |

| Iraq | 25,264 | 548.72 |

| Yemen | 21,457 | 528.72 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1578 | 498.70 |

| Liberia | 2040 | 363.45 |

| Burkina Faso | 6790 | 288.34 |

| Eq. Guinea | 474 | 250.46 |

Note. Table adapted from the WHO Measles and Rubella Global Update 2025

Figure 3. Geographic distribution of the number of reported cases of measles, Jan 2 2024 – Jan 1 2025

Note. Figure reproduced from the WHO Measles and Rubella Global Update 2025

- CDC–Global Measles Outbreaks

- United Nations (UN) Geneva Press Briefing by Alessandra Vellucci, February 20, 2024

Canada:

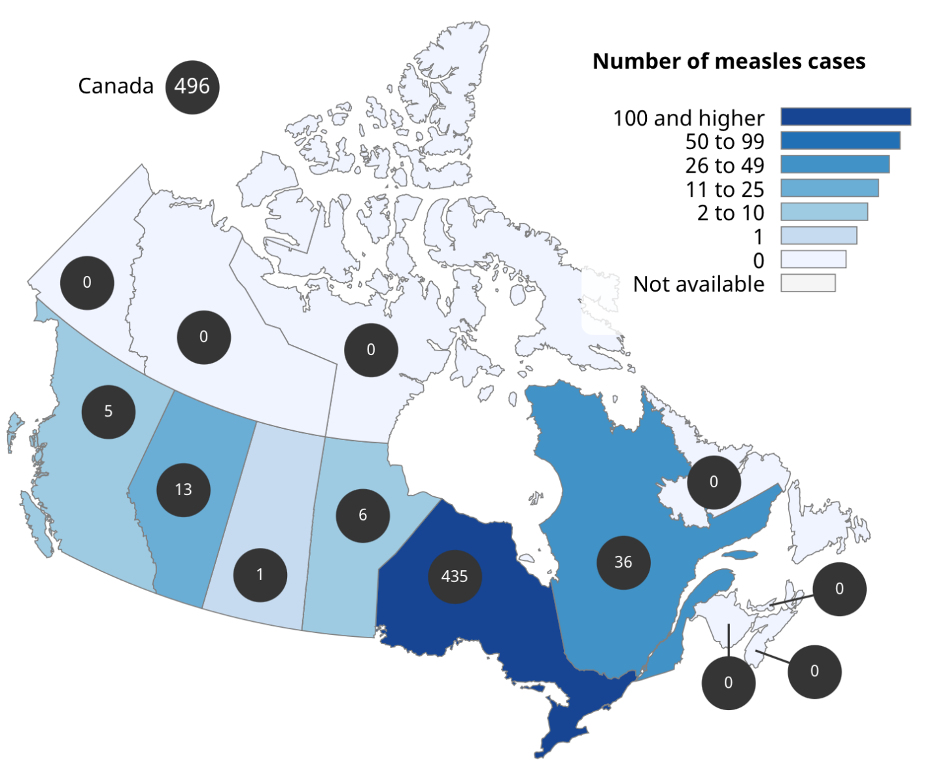

As of March 15, Canada has reported a total of 496 measles cases (410 confirmed, 86 probable) and 0 rubella cases in 2025, compared with a total of 147 cases reported in all of 2024. As of March 15, cases of measles were reported in Alberta (13), British Columbia (5) Manitoba (6), Ontario (435), Quebec (3). 96% of cases were exposed in Canada, epidemiologically and/or virologically linked, 81% of cases were unvaccinated, and 9% were hospitalized.

Figure 4. Geographic distribution of measles cases by province/territory, 2025, as of March 15

Note. Figure reproduced from Government of Canada-Measles & Rubella Weekly Monitoring Report-Week 11: March 9 – March 15, 2025

United States:

As of March 27, 2025, a total of 483 confirmed measles cases were reported by 20 jurisdictions: Alaska, California, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York City, New York State, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, and Washington. For comparison, as of December 31, 2024, a total of 285 measles cases were reported in all of 2024. Of the 483 measles cases, 97% were among the unvaccinated, 14% were hospitalized, and 2 associated deaths.

There have been 5 outbreaks (defined as 3 or more related cases) reported in 2025, and 93% of confirmed cases (447 of 483) are outbreak-associated. For comparison, 16 outbreaks were reported during 2024 and 69% of cases (198 of 285) were outbreak-associated.

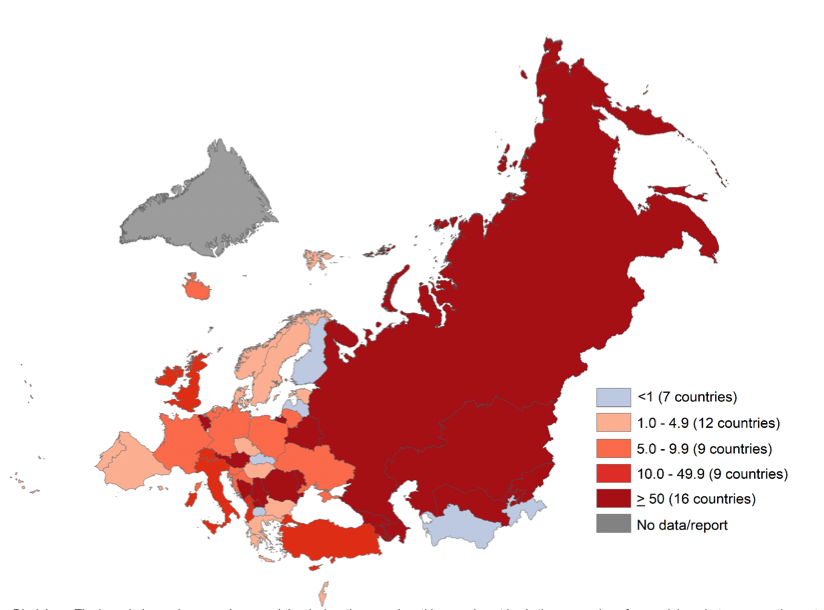

WHO European Region:

From 2022 to 2023, The European Region experienced a more than 60-fold increase in measles cases. Between September 2023 to August 2024, over 138,000 measles cases were reported in 40 of the 53 countries in the European Region, including ten European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA) countries. Of these 138,000 reported cases, 96% were reported in ten countries (Table 3). In 2024, between January and August, 98769 cases were reported.

Table 3. Countries in the WHO European Region with the highest number of measles cases, September 2023 – August 2024

| Country | Reported cases | Incidence per 1 million population |

| Kazakhstan | 38,522 | 1848 |

| Azerbaijan | 30,379 | 2922 |

| Russian Federation | 21,977 | 152 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 18,072 | 2477 |

| Romania | 14,386 | 760 |

| United Kingdom | 2593 | 37 |

| Türkiye | 2367 | 27 |

| Uzbekistan | 2167 | 58 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1660 | 528 |

| Italy | 867 | 14 |

Note. Table reproduced from WHO-Measles and rubella monthly update: WHO European Region-October 1, 2024.

Figure 5. Incidence of measles cases per 1 million population in EU/EAA member state countries, September 2023 to August 2024

Note. Table reproduced from WHO-Measles and rubella monthly update: WHO European Region-October 1, 2024.

What is the current risk for Canadians from measles?

Despite achieving elimination status, there is an increasing risk of imported measles cases in Canada through travel of non-immune people. Individuals who are un- or under vaccinated or who have not had a previous measles infection are at risk of measles infection. Adults born before 1970 who lived in Canada are generally presumed to have acquired immunity due to high levels of circulation before 1970.

Individuals who are at higher risk of complications from measles include:

- Pregnant persons

- Children less than 5 years of age

- People who are immunocompromised

Travel Recommendations

To prevent acquiring measles and spreading the virus to others, it is important for unvaccinated individuals to be vaccinated with a measles-containing vaccine before travelling.

For individuals born before 1970 with no history of measles, one dose of a measles-containing vaccine is recommended before travel.

For individuals born in or after 1970 (12 months or older) with no history of measles, two doses of a measles-containing vaccine are recommended before travel.

Infants under the age of one should receive one dose of the MMR vaccine before travelling and can receive this vaccine starting at 6 months of age.

Measles is categorized by PHAC with a travel health notice of level 1. This level of notice reminds travelers to practice the following health precautions while travelling:

- Ensure recommended vaccinations are up-to-date

- Practice good hand hygiene

- Avoid insect bites

What measures should be taken for a suspected measles case or contact?

Case and Contact Management

Public health authorities should be notified as soon as possible of measles cases. Contacts of measles cases should be classified as either susceptible or non-susceptible within 24 hours of reporting.

Case Definitions

Confirmed case

Laboratory confirmation of infection in the absence of a recent (i.e., within the previous 28 days) immunization with a measles-containing vaccine:

- Isolation of measles virus from an appropriate clinical specimen

OR

- Detection of measles virus RNA

OR

- Significant (e.g., fourfold or greater) increase in measles IgG titre between acute and convalescent sera

OR

- Positive serologic test for measles IgM antibody using a recommended assay in a person who is either epidemiologically linked to a laboratory-confirmed case or has recently travelled to an area with known measles circulation

OR

- Clinical illness in a person with an epidemiologic link to a laboratory-confirmed case

Probable Case

Clinical illness in the absence of either appropriate laboratory tests or an epidemiologic link to a laboratory-confirmed case, or in a person who has recently travelled to an area with known measles circulation.

Suspect Case/Clinical Illness

- High fever (38.3° C or greater)

- Cough, coryza (common cold with a runny nose), or conjunctivitis (red, watery eyes)

- Generalized maculopapular rash for at least three days

- Government of Canada-National case definitions: Measles

- British Columbia Centre for Disease Control-Measles: Case definition

Identifying and Reporting

Measles has been nationally notifiable in Canada since 1924, apart from 1959-1968.

To sustain Canada’s measles elimination status, the Canadian Measles/Rubella Surveillance System (CMRSS) was developed in 1998 and releases weekly reports on the status of measles and rubella in Canada and subsequent weekly reports to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). All suspected measles cases must be reported to PHAC on an urgent basis through public health networks. Please check provincial or territorial guidelines for specific reporting details.