This debrief will focus on HPS/HCPS as this is most common disease in North America

NCCID Disease Debriefs provide Canadian public health practitioners and clinicians with up-to-date reviews of essential information on prominent infectious diseases for Canadian public health practice. While not a formal literature review, information is gathered from key sources including the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO) and peer-reviewed literature.

This disease debrief was prepared by Banneet Brar. Questions, comments, and suggestions regarding this debrief are most welcome and can be sent to nccid@manitoba.ca.

What are Disease Debriefs? To find out more about how information is collected, see our page dedicated to the Disease Debriefs.

Questions Addressed in this debrief:

- What are important characteristics of Hantavirus?

- What is happening with current outbreaks of Hantavirus?

- What is the current risk for Canadians from Hantavirus?

- What measures should be taken for a suspected Hantavirus case or contact?

This debrief will focus on HPS/HCPS as this is most common disease in North America

NCCID Disease Debriefs provide Canadian public health practitioners and clinicians with up-to-date reviews of essential information on prominent infectious diseases for Canadian public health practice. While not a formal literature review, information is gathered from key sources including the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO) and peer-reviewed literature.

Questions Addressed in this debrief:

- What are important characteristics of Hantavirus?

- What is happening with current outbreaks of Hantavirus?

- What is the current risk for Canadians from Hantavirus?

- What measures should be taken for a suspected Hantavirus case or contact?

What are important characteristics of Hantavirus?

Characteristics:

Hantaviruses are a group of viruses that belong to the family Bunynaviridae. These viruses are enveloped with tripartite single-stranded negative sense RNA genome that are enclosed in a spherical capsid. Hantaviruses are categorized into three groups (Muridae, Arvicolinae, Sigmodontinae), based on the taxonomy of the principal host. There are 36 recognized species of hantaviruses. The primary cause of the hantavirus disease in Canada is from the Sin Nombre specie carried by the deer mouse. This strain is characterized as being part of the Sigmodontinae family which is common in North America. Infection from this strain can result in Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS), also known as Hantavirus Cardiopulmonary Syndrome (HCPS).

Cause:

Humans can develop hantavirus disease when infected with any hantavirus strain. The “New World” (North and South America) hantaviruses cause HPS, and hantaviruses in the “Old World” (Eastern Asia and Europe) are known to cause HFRS. There is a specific host (rodent species) for each hantavirus serotype which are pathogenic to humans. Different rodents transmit different types of hantaviruses. In North America, there are 5 known rodents that can cause hantaviruses: deer mouse, cotton rat, rice rat, white-footed mouse, and red-backed vole. The deer mouse is the most common host in Canada. The predominant cause of HPS in North America is from the Sin Nombre specie.

Sign and Symptoms:

HPS (in North and South America), and HFRS (in Europe and Asia) are the two main diseases are caused by hantavirus.

Symptoms for HPS can begin to appear 1 to 8 weeks after exposure to the virus. The course of infection from this virus can be divided into four phases:

- Prodrome phase: lasts about 3 to 6 days.

- Cardiopulmonary phase: rapidly progressive.

- Diuresis phase: characterized by a clearance of pulmonary edema and resolution of both fever and shock.

- Convalescence phase: characterized by a patient’s recovery from the disease.

Symptoms during these phases is characterized by:

- Prodrome:

- fever, myalgia and malaise, headache, dizziness, abdominal pain, and gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Cardiopulmonary:

- non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema, hypoxemia and cough, pleural effusion, gastrointestinal symptoms, tachypnea and tachycardia, myocardial depression, and cardiogenic shock whereby hypotension and oliguria can also occur. Severe symptoms include feeling a shortness of breath, and severe difficulty breathing.

- PHAC-Symptoms of a hantavirus infection

- PHAC- Pathogenicity/Toxicity

- PHAC- Clinical Features

- CDC- Hantavirus HPS Symptoms

- ECDC- Hantavirus Clinical Features

Severity and Complications:

HPS fatality rate is around 30 to 38%. The CDC reports that patients previously infected with HPS that have recovered do not present with any long-term complications.

The PHAC states that depending on the specific strain of the virus, approximately 40% of individuals diagnosed with HPS syndrome will not recover.

Epidemiology:

General

Hantaviruses are found worldwide whereby the distribution of the different types is dependent upon the location of the rodent host. About 200 cases of HPS occur each year in North and South America. Infections are common in rural areas, however, can also be found in urban areas. Most cases of Hantavirus infections present in individuals with occupations as trappers, hunters, forestry workers, farmers, and military personnel. Males between the ages of 20-40 are at a higher risk of infection in comparison to females. This difference can be attributed to the occupations previously mentioned.

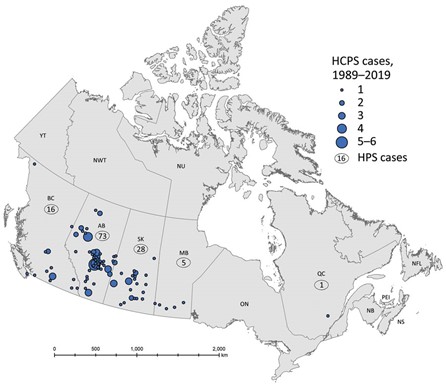

Canada

As of January 1st, 2020, 143 cases of HPS have been confirmed in Canada through Laboratory testing. Annually, there is an average of about 4-5 new cases in Canada. Peak levels of HPS cases are observed with seasonal increases in deer mouse populations in the spring and summer due to increased reproduction. HPS occurs from contact with Sin Nombre hantavirus-infected rodent excreta. Most cases are reported in the southern rural parts of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia.

Incubation Period:

Hantavirus’ incubation period is 2 to 4 weeks whereby this period ranges between 14-17 days for HPS.

Reservoir and Transmission:

Humans are infected with the virus from numerous types of rodents. The deer mouse carrying the Sin Nombre strain is the most common in Canada. Transmission of hantavirus occurs through inhaling virus particles (aerosolized particles) from feces, dust or any organic matter infected with the virus. Transmission may also occur through touching or eating contaminated food from urine, droppings or saliva of infected rodents, and direct contact through cutaneous injuries or mucous membranes with the virus. A rare method of transmission is from being bitten by an infected rodent.

This table lists the most common hantavirus species causing HPS in North America:

| Species | Reservoir | Location of Virus |

| Prospect Hill | Meadow Vole | U.S., CanadaAlaska, Newfoundland & Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Rocky Mountains, N New Mexico, Great Plains, Appalachians, N Georgia |

| Sin Nombre | Deer mouse | U.S., CanadaAlaska Panhandle across N Mexico, continental U.S., excluding SE & E seaboard, southernmost Baja California Sur |

| New York | White-footed mouse | U.S.C and E U.S., S Alberta, S Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia |

Person-to-person transmission is not common. This was only observed in the Andes virus outbreak in Southern Argentina.

Small rodents are the reservoir of hantaviruses. Transmission occurs from rodents to humans. There are no known vectors.

Laboratory Diagnosis:

Hantavirus diagnoses are verified through laboratory testing. One or more of the three diagnostic markers must be positive for indication of infection from hantavirus. The only laboratory in Canada that does diagnostic testing for hantavirus infection in humans is The National Microbiology Laboratory.

The diagnostic markers include:

- hantavirus-specific IgM or rising titers of IgG detection

- hantavirus RNA presence detected by RT-PCR

- positive immunohistochemistry detection for hantavirus antigen

Prevention and Control:

Rodent control should be the first measure taken for the prevention of hantavirus infections. This can be done by controlling rodent populations near human communities. Individuals should avoid contact with rodent urine, droppings, saliva, and nesting materials. Safety measures for proper cleaning and disinfection of rodent-infested areas should be followed (as outlined by the PHAC).

- CDC-How is HFRS prevented?

- CDC- Hantavirus HPS Prevention

- PHAC- How can Hantavirus be Prevented

- BCCDC- Prevention

Hantavirus spreads through contact with infected rodents’ urine, droppings, or saliva which can be through the air, direct contact or by eating. There is no vaccination currently available for hantavirus infection. The PHAC states that the key to disease prevention is preventing rodent infestations, and properly cleaning and disinfecting areas contaminated by rodent droppings

By keeping an individual’s home, workplace and other sites of living rodent-free can be done by blocking openings that could be a passageway for rodents, storing food and garbage in places with tightly fitted lids, using mousetraps, and maintaining yard cleanliness. The virus can survive for 12-15 days in contaminated bedding, 5-11 days in cell culture supernatants at room temperature and for 18-96 days in cell culture supernatants at 4° Celsius.

Effective disinfecting techniques include:

- Wearing a fitted filter mask (which are available at safety supply stores), rubber gloves and goggles

- Ventilating an enclosed area for 30 minutes before cleaning

- Use of any general-purpose disinfectant (i.e., 1 part bleach to 9 parts water) or household detergents

Physical inactivation of the virus can be done by exposure to heat. At a temperature of 56° Celsius, viruses in a cell culture medium exposed for 15 minutes, and 2 hours for dried viruses can inactivate the virus.

Vaccination:

There is currently no vaccination against hantavirus.

Treatment:

Hantavirus infection can be fatal and there is currently no cure for this virus. However, there are treatments that can improve patient outcomes. This includes supportive care, medical aid through maintenance of oxygen levels, and measures to prevent dehydration.

The PHAC suggests exploration of the extracorporeal CO2 elimination system to treat HPS. This treatment prevents life-threatening pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock.

For HPS, recognition of infected individuals early on in the course of infection is crucial for better health outcomes. Infected individuals can receive medical care in an intensive care unit as patients are provided oxygen therapy to help with severe respiratory distress that this virus may cause.

What is happening with current outbreak of Hantavirus?

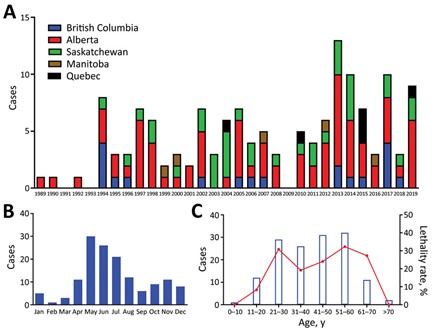

In Canada, active surveillance for hantavirus began in 1994.

Figure:

Figure:

Manitoba:

There have been 5 reported cases of HPS as of 2019.

Ontario:

No cases of HPS have been reported in Ontario.

Alberta:

There have been 16 cases of HPS confirmed in Alberta between 2014 to 2018 whereby 1 case has been fatal. In total, 77 cases of HPS have been reported as of 2019.

British Columbia:

According to the BCCDC, 3 cases of HPS were first reported in British Columbia in 1994. As of 2019, 19 cases have been reported.

Saskatchewan:

As of 2019, 35 cases of HPS have been reported.

Quebec:

There have been 6 cases of HPS reported as of 2019. Five of these cases has been from travel to western provinces or military exercises.

What is the current risk for Canadian from Hantavirus?

There is a low risk of infection from hantavirus. However, anyone coming into contact with hantavirus-infected rodents is at risk.

Infestation of rodents both inside and around homes is the main risk of exposure. Infestations and exposures can occur in places where rodents are present which is inclusive of cottages, trails, and garden sheds.

Travel Recommendations:

It is safe to travel to all areas where hantavirus infection has been reported as safe. Hantavirus is a rare disease, so most tourists are not at increased risk of infection. Individuals that visit nature resorts or rural areas (i.e., campers and hikers) are at higher risk of exposure to rodent droppings, urine or saliva which causes infection. Handling contaminated materials and then touching one’s mouth or nose can cause infection. Risks for infection can be minimized by avoiding touching rodents, airing out unused cabins, disinfecting droppings and disposing of them in a plastic bag, avoid sleeping in bare ground and near garbage, and storing food in sealed containers.

What measures should be taken for a suspected Hantavirus case or contact?

Public Health Ontario has a General Requisition Test posted on its website. This form asks for the specific virus suspected (HFRS or HPS), the onset date, symptoms, and travel history. The website outlines the specimen requirements. Only HPS has been reported in Canada and the U.S.

The BCCDC Public Health Laboratory provides environmental and diagnostic testing whereby a sample container or requisition form can be ordered from their website.

Case and Contact Management:

If an individual has come into contact with rodents or rodent droppings and/or urine or is experiencing the listed symptoms they should contact a health care provider. Details about contact with rodents and/or their droppings and/or urine should be provided so rodent-specific diseases such as hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, and haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome can be explored.

Case Definitions:

The Canadian Government is responsible for providing information on hantaviruses and diseases caused by the viruses. The National Microbiology Laboratory is the only laboratory in Canada that conducts diagnostic testing for hantavirus infections in humans, analyzes trends in hantavirus pulmonary syndrome cases in Canada, and carries out field investigations into hantavirus infection cases across Canada.

Clinical illness is confirmed with laboratory confirmation of infection through 1 of 3 methods: IgM antibody to Hantavirus detection, increased hantavirus-specific IgG antibody titres, hantavirus-specific RNA detection, or detection of the hantavirus antigen from immunohistochemistry. The definition of a clinical illness is indicated by febrile illness (oral temperature greater than 38.3° Celsius) that requires oxygen along with bilateral diffuse infiltrates, and the development of infection within 72 hours of hospitalization.

Identifying and Reporting:

HPS became a nationally reportable disease in 2000.

If an individual is experiencing symptoms and has been in contact with rodent droppings, urine or saliva, it is recommended by the PHAC to contact your physician and indicate potential exposure to rodents.

As per Public Health Ontario, test results are reported to the health care provider ordering the test. Positive results are reported to the Medical Officer of Health as required by the Health Protection and Promotion Act.

Infection Control and Prevention:

Since there is no vaccine for hantavirus, prevention is necessary. The PHAC recommends proper cleaning and disinfection of areas contaminated by rodent droppings.