Updated February 1, 2024

NCCID Disease Debriefs provide Canadian public health practitioners and clinicians with up-to-date reviews of essential information on prominent infectious diseases for Canadian public health practice. While not a formal literature review, information is gathered from key sources including the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO) and peer reviewed literature.

This debrief was prepared by Signy Baragar. Questions, comments and suggestions regarding this debrief are most welcome and can be sent to nccid@umanitoba.ca.

What are Disease Debriefs? To find out more about how information is collected, see our page dedicated to the Disease Debriefs.

What are important characteristics of Group A streptococcal disease?

Cause and pathogensis

Group A streptococcal disease (GAS) is caused by the bacteria Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes) – gram positive, beta-hemolytic bacteria that can be found on the skin or in the throat. The bacteria have spherical, non-motile, and non-spore forming cells that usually occur in chains.

Several virulence factors contribute to human infection by GAS via the secretion or release of a variety of extracellular products. The main virulence factors include, but are not limited to, the presence of M protein fragments assisting with GAS colonization, invasions by the toxins streptolysin S and O, bacterial dissemination by streptokinase, and more.

GAS is responsible for a range of diseases ranging from non-invasive to invasive. The vast majority of GAS diseases are mild and non-invasive, such as strep throat (acute pharyngitis), skin and soft tissue infections (e.g., impetigo and cellulitis), and fevers and rashes (e.g., scarlet fever). In rare cases, S. pyogenes enter parts of the body where bacteria are not normally found, such as in the blood, deep tissue, or lungs. These infections are called invasive GAS (iGAS) and can lead to severe diseases such as necrotizing fasciitis (flesh eating disease), toxic shock syndrome (TSS), and lung infections (e.g., pneumonia)

Government of Canada – Group A streptococcal diseases (Streptococcus pyogenes)

Brouwer et al., 2023 – Pathogenesis, Epidemiology and Control of Group A Streptococcus Infection

Signs, symptoms, and complications

The vast majority of GAS infections are mild and non-invasive. General symptoms include:

- Sore, painful throat

- Fever

- Mild skin infections (rashes, sores, bumps, blisters)

However, signs and symptoms of GAS will vary depending on the disease.

Government of Canada – Group A streptococcal diseases (Streptococcus pyogenes)

Strep throat (streptococcal pharyngitis)

Symptoms of strep throat usually include:

- Sore, red throat

- Pain when swallowing

- Inflamed, red tonsils and/or white patches on tonsils

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Petechiae (red spots on the roof of the mouth)

Less common symptoms may include headaches, vomiting, abdominal pain, and scarlet fever (rash) and typically affect children.

Strep throat symptoms usually occur within two to five days after being exposed to GAS and can resolve within one week without treatment. However, antibiotic treatment is encouraged to prevent severe manifestations and spreading the bacteria to others.

In rare cases, strep throat can lead to rheumatic fever, kidney disease, ear and sinus infections, and abscesses around the tonsils or in the neck.

Given the overlapping symptoms with other respiratory viral infections, it is important to note that coughs, rhinorrhea (runny nose), hoarseness, and conjunctivitis (pink eye) are not typically seen in patients with strep throat, and are strongly suggestive of virus etiology rather than strep throat.

Government of Canada Streptococcal diseases: Symptoms and treatment

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – Strep Throat: All You Need to Know

Scarlet fever

Scarlet fever is most common among children aged 5 to 18 years. Individuals with scarlet fever may have red, blanching rashes with tiny bumps that feel like sandpaper. The rash may first appear as small, flat blotches on the torso, neck, under arm, and groin before spreading to other parts of the body. Usually, the tongue is also coated in a yellowish, white film with red dots (papillae) before becoming bright red and bumpy (known as strawberry tongue).

Other common symptoms of scarlet fever may include a high-grade fever (38.3ºC or 101ºF); a very sore, red throat; pain when swallowing; and swollen lymph nodes in the neck that are tender to the touch. Less common signs and symptoms of scarlet fever include headache or body aches, nausea or vomiting, and stomach pain.

Scarlet fever symptoms usually occur within one to five days after the onset of illness and the rash lasts about one week. As the rash resolves, peeling of the skin may occur for several weeks.

In rare cases, scarlet fever can lead to post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN) and rheumatic fever.

Public Health Agency of Canada – Scarlet Fever Fact Sheet

CDC – For Clinicians – Scarlet Fever

CDC – Scarlet Fever: All You Need to Know

Rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever usually occurs as an immune response to a strep throat infection or scarlet fever that have not been treated with antibiotics. Symptoms include:

- Fever

- Arthritis (painful, tender joints)

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Fast heartbeat

- Heart murmur

- Fatigue

- Chorea (involuntary, random body movements)

Less common symptoms include a red, non-itching, and painless rash which has serpiginous configuration (wavy, serpent-like elevations or lines) or small, painless bumps (nodules).

Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada – Rheumatic heart disease

CDC – For Clinicians – Acute Rheumatic Fever

Nonbullous impetigo (impetigo contagiosa)

Nonbullous impetigo is most common in young children. Symptoms include red sores (appearing as tiny blisters or red bumps) that break open and leak fluid or pus. As the fluid dries, the sores develop yellow or “honey-coloured” scabs. Itching is usually mild and the sores generally heal without scarring.

Complications from impetigo are rare but can include post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (kidney disease) and rheumatic fever.

CDC – For Clinicians – Impetigo

CDC – Impetigo: All You Need to Know

Flesh-eating disease (necrotizing fasciitis)

Flesh-eating disease is a rare, invasive, and life-threatening condition that can be caused by GAS. Symptoms include a sudden onset of swelling and severe pain at the site of a wound which spreads quickly, as well as fever.

Later symptoms may include:

- Diarrhea

- Nausea

- Fatigue

- Ulcers, blisters, or black spots on the skin

- Dizziness

- Changes in skin colour

Flesh-eating disease can result in tissue death (gangrene), sepsis, shock, and organ failure, and can be lethal in 12-24 hours.

HealthLinkBC – Necrotizing Fasciitis (Flesh-Eating Disease)

Government of Manitoba – Necrotizing Fasciitis (“Flesh-eating Disease”)

CDC – Necrotizing Fasciitis: All You Need to Know

Cellulitis

Initial symptoms of cellulitis include warmth, redness, swelling, pain, or tenderness in an area of skin. As the infection spreads, symptoms can also include:

- Chills

- Fever

- Swollen lymph nodes

In rare cases, cellulitis can result in bacteremia (blood infection) and infections in the deep tissue including: septic thrombophlebitis (blood clots in veins that cause inflammation), infective endocarditis (inflammation of the heart valves or inner lining of the heart), suppurative arthritis (bacterial infection in a joint), and osteomyelitis (bone infection).

Government of Alberta – Cellulitis: Condition Basics

CDC – Cellulitis: All You Need to Know

Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS)

Initial symptoms of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) are usually flu-like and may include fever, chills, malaise, vomiting, nausea, and muscle aches. Approximately 24-48 hours after symptom onset, an infected individual’s blood pressure can drop with symptoms progressing to sepsis with hypotension (low blood pressure), tachycardia (faster than normal heart rate), tachpnea (rapid breathing), and organ failure.

British Columbia Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) – Streptococcal Disease, Invasive, Group A

CDC – Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome: All You Need to Know

CDC – For Clinicians – Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN)

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN) is a rare kidney disease that usually occurs as an immune response approximately 10 days after a strep throat infection or scarlet fever, or 3 weeks after impetigo. Symptoms may include:

- Macroscopic hematuria (visible blood in the urine which makes urine appear dark, reddish-borne, or tea-coloured)

- Edema (swelling), often on the face, around the eyes, hands, and feet

- Decreased urine output

- Fatigue or general weakness

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

Some infected individuals with PSGN may not notice any symptoms or have mild enough symptoms that they do not seek medical attention.

CDC – For Clinicians – Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis

CDC – Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis: All You Need to Know

Incubation period

The incubation period for GAS is not clearly defined and depends on the clinical syndrome.

Non-invasive GAS, such as strep throat and scarlet fever, generally have incubation periods of 2 to 5 days, with the exception of impetigo, which has an incubation period of approximately 10 days.

iGAS incubation periods are usually 1 to 3 days, however vary depending on the disease. For example, the incubation period for hypotension from STSS varies on the site of entry and generally occurs between 24-48 hours after the onset of initial symptoms. PSGN typically occurs up to 3 weeks after GAS skin infections (e.g., impetigo and cellulitis).

CDC – For Clinicians – Pharyngitis (Strep Throat)

CDC – For Clinicians – Scarlet Fever

CDC – For Clinicians – Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome

CDC – For Clinicians – Impetigo

CDC – For Clinicians – Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis

Reservoir and transmission

GAS is generally spread person-to-person by fluid secretions from the nose and throat of an infected person (via coughing or sneezing) or by direct contact with infected wounds on the skin. Foodborne outbreaks of GAS have also been reported via the consumption of S. pyogenes-contaminated food (e.g., unpasteurized milk, premade foods containing eggs).

It is rare for GAS transmission to occur through indirect contact with objects or through the air.

Government of Canada – Group A streptococcal diseases (Streptococcus pyogenes)

PHAC- Pathogen Safety Data Sheets: Infectious Substances – Streptococcus pyogenes

Alberta Public Health Disease Management Guidelines – Streptococcal Disease Group A, Invasive

Laboratory diagnoses

Diagnoses for GAS are generally made by isolating GAS from a normally sterile site (e.g., blood, tissue from deep inside a wound, cerebrospinal fluid). However, diagnoses vary depending on the clinical syndrome.

All laboratories must submit confirmed GAS isolates to the National Centre for Streptococcus (NCS) in Alberta for M-protein serotyping.

Alberta Public Health Disease Management Guidelines – Streptococcal Disease Group A, Invasive

Strep throat and scarlet fever

For group A strep pharyngitis and scarlet fever with pharyngitis, the gold standard test is a throat culture. A rapid antigen detection test (RADT) can also be used and has a high specificity for group A strep, however, its sensitivities vary when compared to throat culture tests.

CDC – For Clinicians – Pharyngitis (Strep Throat)

CDC – For Clinicians – Scarlet Fever

Rheumatic fever

Acute rheumatic fever does not have a specific diagnostic test. Due to the broad array of symptoms, differential diagnoses of acute rheumatic fever may include: lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, septic arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and more.

CDC – For Clinicians – Acute Rheumatic Fever

Nonbullous impetigo

Laboratory testing is not needed nor performed in clinical practice for nonbullous impetigo. To diagnose, doctors typically examine sores during a physical examination. It can be difficult, however, to reliably differentiate between streptococcal and staphylococcal nonbullous impetigo with a physical examination.

CDC – For Clinicians – Impetigo

CDC – Impetigo: All You Need to Know

Flesh-eating disease

Flesh-eating disease is diagnosed clinically based on a high level of suspicion for patients presenting with severe, profound pain at the site of a wound. However, when symptoms are non-specific (e.g., unexplained fever, pain, edema), it can be difficult to differentiate between flesh-eating disease and cellulitis.

Laboratory tests for flesh-eating disease may include:

- Complete blood counts (CBC), such as leukocytosis

- Platelets (thrombocytopenia)

- Eclectrolytes

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

- Glomerular filtration rate (GFR)

- C-reactive protein (CRP)

- International normalized ratio (INR)

- Liver function tests (LFTs)

- Electrocardiogram (ECG)

Gram stains may also be used to determine whether the disease is caused by GAS.

Emergency Care BC – Point-of-Care Emergency Clinical Summary – Necrotizing Fasciitis Diagnosis

BC Cancer – Lab Test Interpretation Table

CDC – For Clinicians – Type II Necrotizing Fasciitis

Cellulitis

Cellulitis is typically diagnosed clinically. Blood and other lab tests are usually not needed.

CDC – Cellulitis for Health Care Providers

Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS)

In the early stages of STSS, differential diagnosis may be broad and include staphylococcal toxic shock or other viral or bacterial infections. Laboratory tests may include blood cultures (which are commonly, but not universally positive), blood tests, and urine tests.

Emergency Care BC – Point-of-Care Emergency Clinical Summary – Toxic Shock Syndrome -Diagnosis

CDC – For Clinicians – Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome

John Hopkins Medicine – Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS)

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN)

Diagnosis of PSGN includes evidence of preceding infection with GAS. Evidence can include having elevated streptococcal antibodies and the isolation of GAS from skin lesions or the throat.

CDC – For Clinicians – Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis

Prevention and control

One of the best ways to protect yourself from GAS is by washing your hands after coughing and sneezing, and before eating and preparing food.

To reduce the spread of GAS by respiratory droplets from the nose or throat, good respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette should also be practiced. This includes:

- Coughing or sneezing into a tissue and discarding the tissue after use

- Coughing or sneezing into the bend of your arm, not your hands, when tissues are unavailable

- Washing your hands often with soap and water, or using hand sanitizer, before touching your face (eyes, nose, and mouth)

Breaks in the skin, such as wounds or cuts, can provide an opportunity for S. pyogenes to enter the body. Therefore, it is also important to keep all breaks in the skin clean and to watch for signs of infection (i.e., swelling, redness, pain, drainage).

Government of Canada – Group A Streptococcal Diseases: Risks and Prevention

BCCDC – Streptococcal Disease, Invasive, Group A

Vaccination

There is currently no vaccine to prevent GAS infections, although vaccine initiatives are in development.

In 2018, the World Health Organization released the GAS Vaccines Research and Development (R&D) roadmap and Preferred Product Characteristics (PPC) for the development of novel GAS vaccines. Recent advances on these developments can be found in the 2022 presentation, WHO expert review of Group A Streptococcus vaccines.

PHAC- Pathogen Safety Data Sheet- Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Strep)

Treatment

Treatment will vary depending on the type of GAS disease. In the absence of a GAS vaccine, antibiotics (e.g., penicillin, macrolide, or cephalosprin) are used to treat most GAS diseases. However, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) stewardship strategies should be considered to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use. For example, according to Choosing Wisely Canada, when treating group A pharyngitis, consider only using antibiotics in confirmed bacterial pharyngitis and delaying antibiotics while awaiting throat swab results. For more information on using antibiotics wisely, visit Choosing Wisely Canada.

PHAC- Pathogen Safety Data Sheets: Infectious Substances – Streptococcus pyogenes

Epidemiology

General

iGAS diseases are a global cause of morbidity and mortality, but are more prevalent in populations who are living in overcrowded conditions or in socioeconomically disadvantaged regions. Globally, iGAS diseases are responsible for more than 500,000 deaths annually.

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, several countries have witnessed an increase in iGAS. In December 2022, the World Health Organization reported an increase in iGAS cases and deaths across Europe (including France, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Sweden). Similarly, in December 2022, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a health advisory for a spike in pediatric iGAS cases.

PHAC- Pathogen Safety Data Sheets: Infectious Substances – Streptococcus pyogenes

Canada

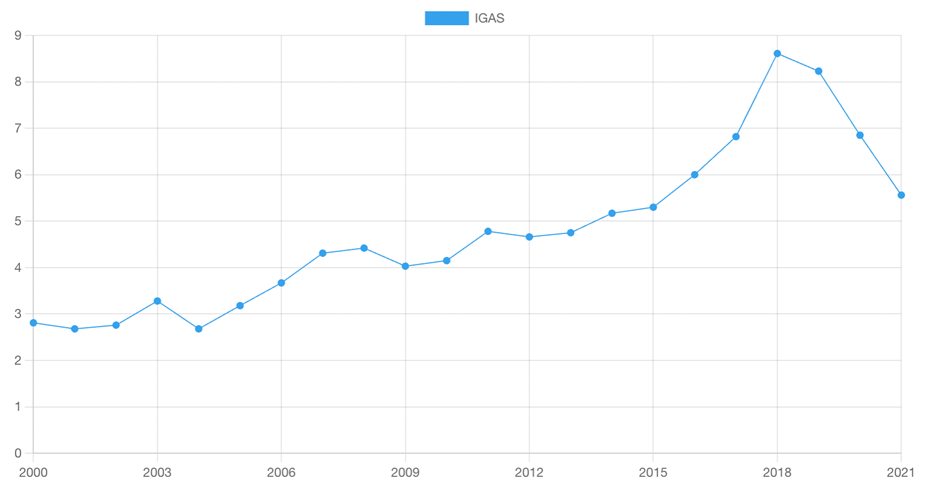

iGAS is endemic in Canada, with the average number of cases rising steadily since 2000. Preliminary data from the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) reported over 4,600 samples submitted to the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) in January 2023 – a record number for the country. The previous peak occurred in 2019 at roughly 3,200 cases.

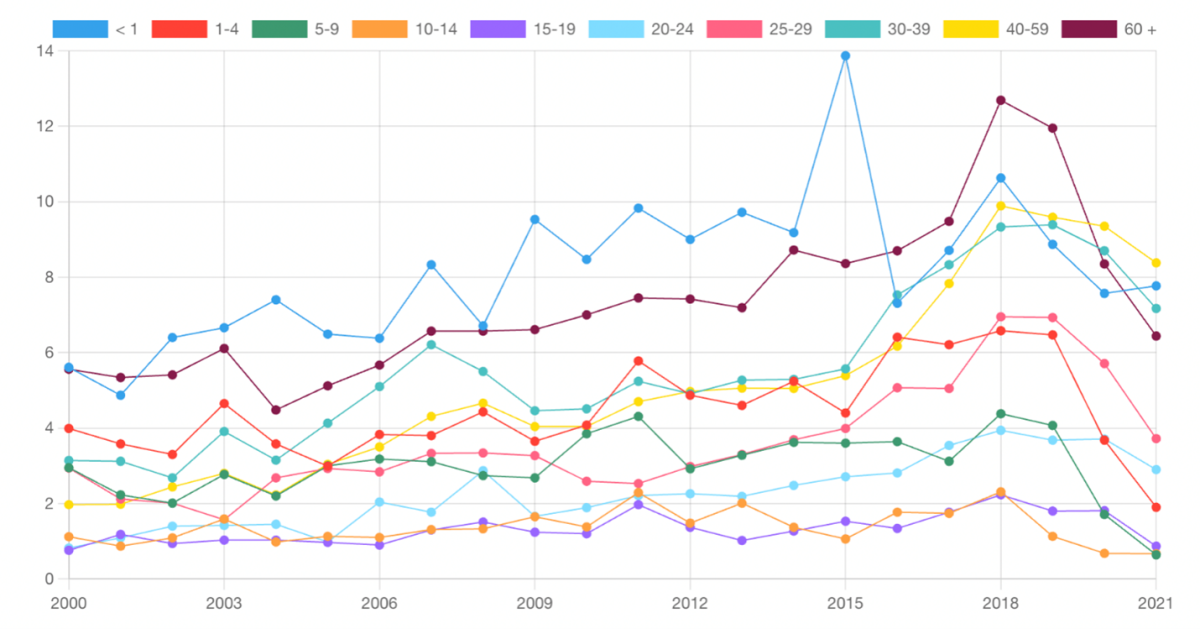

Between 2000 and 2021, the age groups most affected by iGAS were infants under 1 year of age (8.15 cases per 100,000 reported cases), followed by adults over 60 years of age (7.33 cases per 100,000 reported cases), adults aged 30-39 years (5.57 cases per 100,000 reported cases), and adults aged 40-59 years (5.06 cases per 100,000 reported cases).

Figure 1. Rate per 100,000 of reported cases of iGAS in Canada, 2000-2021

Note. From Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System – Group A Streptococcal Disease, Invasive

Figure 2. Rate per 100,000 reported cases of iGAS in Canada, by age group, 2000-2021

In 2020, Ontario reported the highest number of iGAS isolates at 1,063, followed by Alberta (n=458), Quebec (n=345), British Columbia (n=338), Saskatchewan (n=272), and Manitoba (n=268). Atlantic Canada (New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador) reported 99 iGAS isolates, of which, 53 were from New Brunswick. Northern Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut) reported a total of 24 iGAS isolates in 2020.

Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System – Group A Streptococcal Disease, Invasive

Golden et al., 2022. Invasive Group A Streptococcal Disease Surveillance in Canada, 2020.

United States

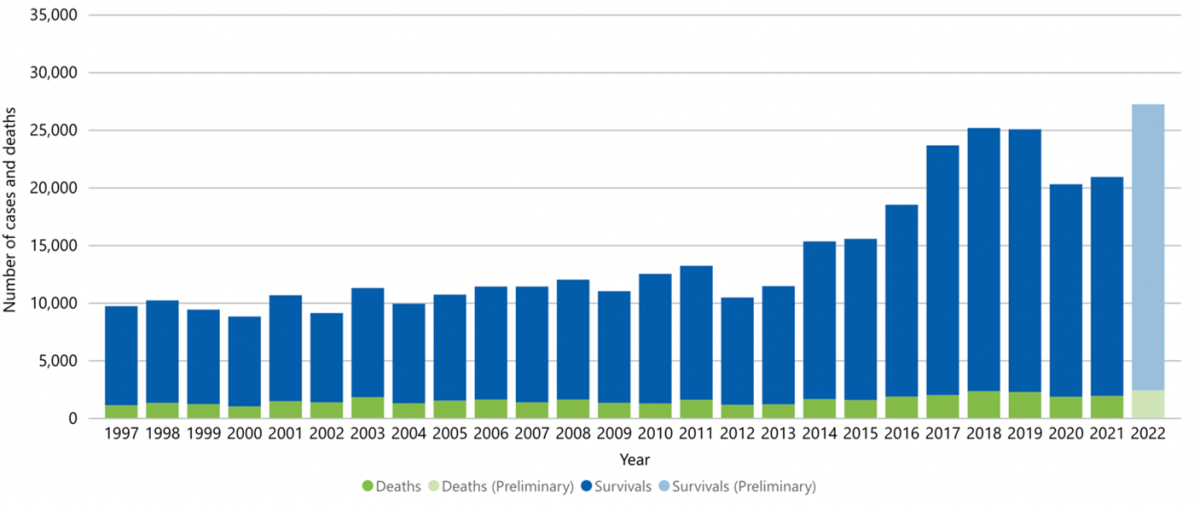

The average number of iGAS cases has risen in the United States in the past two decades. Several million cases of noninvasive GAS and between 14,000 to 25,000 cases of iGAS occur in the U.S. each year. iGAS has also contributed to between 1,500 to 2,300 deaths annually in the U.S. in the past five years.

Figure 3. Number of iGAS cases and deaths in the U.S. between 1997 to 2022.

Note. From CDC – Bact Facts Interactive – Data Dashboard – Group A Streptococcus (GAS)

CDC – Group A Streptococcal (GAS) Disease – Surveillance

CDC – Bact Facts Interactive – Data Dashboard – Group A Streptococcus (GAS)

What is happening with current outbreaks of invasive Group A streptococcal disease?

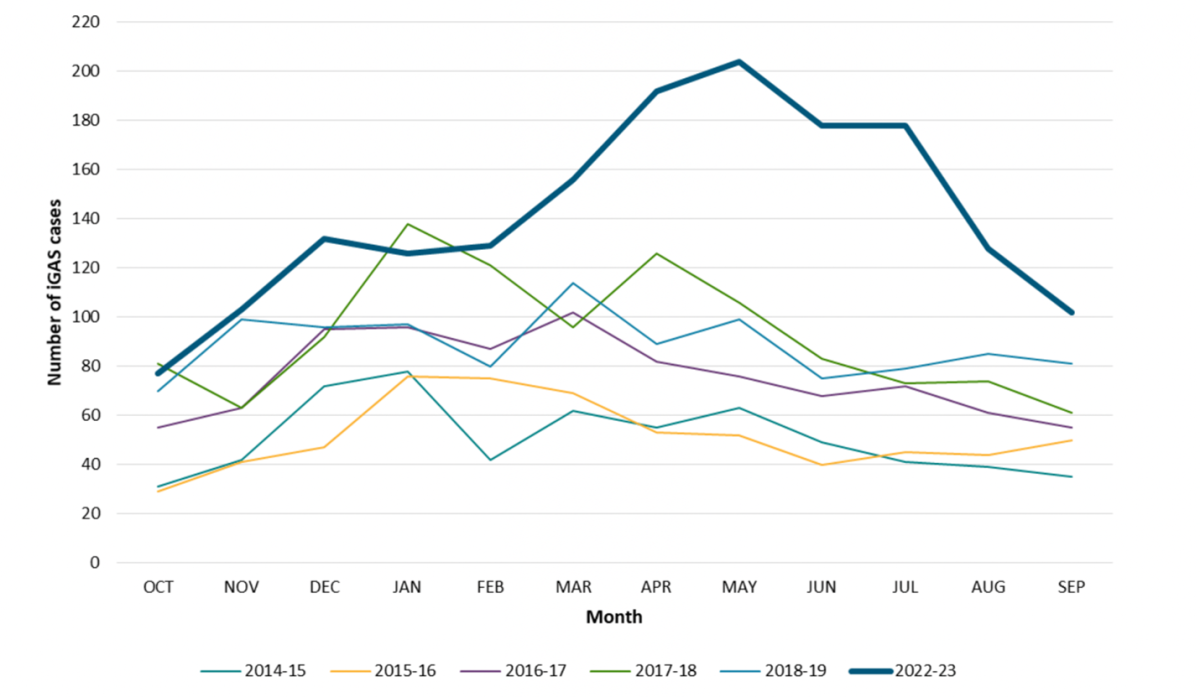

Since 2022, increases in iGAS cases and deaths have been reported in several provinces across Canada. For example, the iGAS-related mortality in New Brunswick increased from 6 deaths annually (2018-2022) to 10 deaths in 2023. Within the first two weeks of January 2024, 2 deaths have already occurred including in a child under the age of 9. In Ontario, the number of iGAS cases between October 1, 2022 to September 30, 2023 was higher compared to previous pre-pandemic seasons (Figure 4). By December 2023, Ontario recorded its highest monthly record at 222 new iGAS cases.

Figure 4. Confirmed iGAS case counts in Ontario by current season (1 October 2022 – 30 September 2023) compared to five pre-pandemic seasons (1 October 2014 – 30 September 2019).

Additional epidemiological information for regions elsewhere in Canada will be made available shortly.

What is the current risk for Canadians from Group A streptococcal disease?

Because GASis commonly transmitted person-to-person by coughing or sneezing, transmission rates are higher in overcrowded and/or enclosed social settings, such as schools, nurseries, hospitals, homeless shelters, and residential care homes.

Risk factors for GAS infection have also been associated with:

- Underlying, chronic medical conditions including:

- Diabetes

- Lung disease

- Liver disease

- Heart disease

- Weakened immune systems caused by:

- Cancer treatments (radiation, chemotherapy)

- Disease (HIV infection, AIDS)

- Anti-injection drugs following organ or bone-marrow transplants

- Breaks in the skin including:

- Wounds

- Cuts

- Burns

- Open Sores

- Varicella infection

- Substance abuse, including use of injectable drugs

- Recent close contact with someone infected with GAS

Additionally, several studies have examined population groups that may be at higher risk of GAS infection. Other at-risk groups identified in the literature include:

- Pregnant persons, persons with postpartum status, and neonates

- Children under the age of 15 years

- Persons identifying as male

- Elderly

- People living in poor housing conditions (e.g., dampness, poor ventilation, poor house temperature).

- People exposed to:

- tobacco smoke

- biting insects

- skin injuries

Government of Canada – Group A Streptococcal diseases: For Health Professionals

What measures should be taken for a suspected Group A streptococcal disease case or contact?

Individuals suspected of having a GAS infection should seek medical care for testing and treatment immediately.

Close contacts of a person infected with iGAS should monitor for symptoms of iGAS and seek medical care if clinical manifestations develop. Close contacts can be defined as:

- Household contacts of a person infected with iGAS who have spent an average of at least 4 hours/day in the last 7 days or 20 hours/week with a person infected with iGAS

- Non-household persons who share the same bed or had sexual relations with a person infected with iGAS

- Persons who have made direct contact with oral or nasal secretions (e.g. mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, open mouth kissing) of a person infected with iGAS or unprotected direct contact with an open skin lesion of a person infected with iGAS

- Persons who inject drugs and have shared needles with a person infected with iGAS

Case Definitions

Confirmed Case

- Isolation of Group A Streptococcus pyogenes or deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)detection by nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT)from a normally sterile site (blood, cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid, peritoneal fluid, pericardial fluid, bone or joint fluid, or specimens taken during surgery) with or without evidence of severe invasive disease.

Probable Case

- Isolation of Group A Streptococcus from a non-sterile site (e.g., skin) in the absence of another identified etiology, with evidence of severe invasive disease.

Government of Canada – National Case Definition: Invasive Group A Streptococcal Disease, 2008

Identifying and Reporting

Confirmed cases of iGAS have been nationally notifiable in Canada since January 2000. Provinces and Territories are responsible for reporting confirmed cases of iGAS to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) through the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS). Surveillance is conducted through routine case-by-case notification to the federal level.

Provincial and territorial public health laboratories can receive assistance from the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) for GAS outbreak investigations upon request.

Government of Canada – National Case Definition: Invasive Group A Streptococcal Disease, 2008

Golden et al., 2022. Invasive Group A Streptococcal Disease Surveillance in Canada, 2020.