Are you looking for the PHAC guidance document for practitioners?

Updated October 10, 2025

NCCID Disease Debriefs provide Canadian public health practitioners and clinicians with up-to-date reviews of essential information on prominent infectious diseases for Canadian public health practice. While not a formal literature review, information is gathered from key sources including the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO) and peer reviewed literature.

This debrief was prepared by Signy Baragar. Questions, comments and suggestions regarding this debrief are most welcome and can be sent to nccid@umanitoba.ca.

What are Disease Debriefs? To find out more about how information is collected, see our page dedicated to the Disease Debriefs.

What are important characteristics of Group A streptococcal disease?

Cause and pathogensis

Group A streptococcal disease (GAS) is caused by the bacteria Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes) – gram positive, beta-hemolytic bacteria that can be found on the skin or in the throat. The bacteria have spherical, non-motile, and non-spore forming cells that usually occur in chains.

Several virulence factors contribute to human infection by GAS via the secretion or release of a variety of extracellular products. The main virulence factors include, but are not limited to, the presence of M protein fragments assisting with GAS colonization, invasions by the toxins streptolysin S and O, bacterial dissemination by streptokinase, and more.

GAS is responsible for a range of diseases ranging from non-invasive to invasive. The vast majority of GAS diseases are mild and non-invasive, such as strep throat (acute pharyngitis), skin and soft tissue infections (e.g., impetigo and cellulitis), and fevers and rashes (e.g., scarlet fever). In rare cases, S. pyogenes enter parts of the body where bacteria are not normally found, such as in the blood, deep tissue, or lungs. These infections are called invasive GAS (iGAS) and can lead to severe diseases such as necrotizing fasciitis (flesh eating disease), toxic shock syndrome (TSS), and lung infections (e.g., pneumonia)

Government of Canada – Group A streptococcal diseases (Streptococcus pyogenes)

Brouwer et al., 2023 — Pathogenesis, Epidemiology and Control of Group A Streptococcus Infection

Signs, symptoms, and complications

The vast majority of GAS infections are mild and non-invasive. General symptoms include:

- Sore, painful throat

- Fever

- Mild skin infections (rashes, sores, bumps, blisters)

However, signs and symptoms of GAS will vary depending on the disease.

Government of Canada — Group A streptococcal diseases (Streptococcus pyogenes)

Strep throat (streptococcal pharyngitis)

Symptoms of strep throat usually include:

- Sore, red throat

- Pain when swallowing

- Inflamed, red tonsils and/or white patches on tonsils

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Petechiae (red spots on the roof of the mouth)

Less common symptoms may include headaches, vomiting, abdominal pain, and scarlet fever (rash) and typically affect children.

Strep throat symptoms usually occur within two to five days after being exposed to GAS and can resolve within one week without treatment. However, antibiotic treatment is encouraged to prevent severe manifestations and spreading the bacteria to others.

In rare cases, strep throat can lead to rheumatic fever, kidney disease, ear and sinus infections, and abscesses around the tonsils or in the neck.

Given the overlapping symptoms with other respiratory viral infections, it is important to note that coughs, rhinorrhea (runny nose), hoarseness, and conjunctivitis (pink eye) are not typically seen in patients with strep throat, and are strongly suggestive of virus etiology rather than strep throat.

PHAC — Pathogen Safety Data Sheet — Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Strep)

Government of Canada — Streptococcal diseases: Symptoms and treatment

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) — Strep Throat

Scarlet fever

Scarlet fever is most common among children aged 5 to 18 years. Individuals with scarlet fever may have red, blanching rashes with tiny bumps that feel like sandpaper. The rash may first appear as small, flat blotches on the torso, neck, under arm, and groin before spreading to other parts of the body. Usually, the tongue is also coated in a yellowish, white film with red dots (papillae) before becoming bright red and bumpy (known as strawberry tongue).

Other common symptoms of scarlet fever may include a high-grade fever (38.3ºC or 101ºF); a very sore, red throat; pain when swallowing; and swollen lymph nodes in the neck that are tender to the touch. Less common signs and symptoms of scarlet fever include headache or body aches, nausea or vomiting, and stomach pain.

Scarlet fever symptoms usually occur within one to five days after the onset of illness and the rash lasts about one week. As the rash resolves, peeling of the skin may occur for several weeks.

In rare cases, scarlet fever can lead to post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN) and rheumatic fever.

Public Health Agency of Canada — Scarlet Fever Fact Sheet

CDC — Clinical Considerations for Group A Streptococcus

Rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever usually occurs as an immune response to a strep throat infection or scarlet fever that have not been treated with antibiotics. Symptoms include:

- Fever

- Arthritis (painful, tender joints)

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Fast heartbeat

- Heart murmur

- Fatigue

- Chorea (involuntary, random body movements)

Less common symptoms include a red, non-itching, and painless rash which has serpiginous configuration (wavy, serpent-like elevations or lines) or small, painless bumps (nodules).

Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada — Rheumatic heart disease

Nonbullous impetigo (impetigo contagiosa)

Nonbullous impetigo is most common in young children. Symptoms include red sores (appearing as tiny blisters or red bumps) that break open and leak fluid or pus. As the fluid dries, the sores develop yellow or “honey-coloured” scabs. Itching is usually mild and the sores generally heal without scarring.

Complications from impetigo are rare but can include post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (kidney disease) and rheumatic fever.

Flesh-eating disease (necrotizing fasciitis)

Flesh-eating disease is a rare, invasive, and life-threatening condition that can be caused by GAS. Symptoms include a sudden onset of swelling and severe pain at the site of a wound which spreads quickly, as well as fever.

Later symptoms may include:

- Diarrhea

- Nausea

- Fatigue

- Ulcers, blisters, or black spots on the skin

- Dizziness

- Changes in skin colour

Flesh-eating disease can result in tissue death (gangrene), sepsis, shock, and organ failure, and can be lethal in 12-24 hours.

HealthLinkBC — Necrotizing Fasciitis (Flesh-Eating Disease)

Government of Manitoba — Necrotizing Fasciitis (“Flesh-eating Disease”)

Cellulitis

Initial symptoms of cellulitis include warmth, redness, swelling, pain, or tenderness in an area of skin. As the infection spreads, symptoms can also include:

- Chills

- Fever

- Swollen lymph nodes

In rare cases, cellulitis can result in bacteremia (blood infection) and infections in the deep tissue including: septic thrombophlebitis (blood clots in veins that cause inflammation), infective endocarditis (inflammation of the heart valves or inner lining of the heart), suppurative arthritis (bacterial infection in a joint), and osteomyelitis (bone infection).

Government of Alberta — Cellulitis: Condition Basics

Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS)

Initial symptoms of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) are usually flu-like and may include fever, chills, malaise, vomiting, nausea, and muscle aches. Approximately 24-48 hours after symptom onset, an infected individual’s blood pressure can drop with symptoms progressing to sepsis with hypotension (low blood pressure), tachycardia (faster than normal heart rate), tachpnea (rapid breathing), and organ failure.

British Columbia Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) — Streptococcal Disease, Invasive, Group A

CDC — Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome

CDC — For Clinicians — Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN)

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN) is a rare kidney disease that usually occurs as an immune response approximately 10 days after a strep throat infection or scarlet fever, or 3 weeks after impetigo. Symptoms may include:

- Macroscopic hematuria (visible blood in the urine which makes urine appear dark, reddish-borne, or tea-coloured)

- Edema (swelling), often on the face, around the eyes, hands, and feet

- Decreased urine output

- Fatigue or general weakness

- Hypertension (high blood pressure)

Some infected individuals with PSGN may not notice any symptoms or have mild enough symptoms that they do not seek medical attention.

CDC — For Clinicians — Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis

CDC — Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis

Incubation period

The incubation period for GAS is not clearly defined and depends on the clinical syndrome.

Non-invasive GAS, such as strep throat and scarlet fever, generally have incubation periods of 2 to 5 days, with the exception of impetigo, which has an incubation period of approximately 10 days.

iGAS incubation periods are usually 1 to 3 days, however vary depending on the disease. For example, the incubation period for hypotension from STSS varies on the site of entry and generally occurs between 24-48 hours after the onset of initial symptoms. PSGN typically occurs up to 3 weeks after GAS skin infections (e.g., impetigo and cellulitis).

CDC — For Clinicians — Pharyngitis (Strep Throat)

CDC — For Clinicians — Scarlet Fever

CDC — For Clinicians — Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome

CDC — For Clinicians — Impetigo

CDC — For Clinicians — Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis

Reservoir and transmission

GAS is generally spread person-to-person by fluid secretions from the nose and throat of an infected person (via coughing or sneezing) or by direct contact with infected wounds on the skin. Foodborne outbreaks of GAS have also been reported via the consumption of S. pyogenes-contaminated food (e.g., unpasteurized milk, premade foods containing eggs).

It is rare for GAS transmission to occur through indirect contact with objects or through the air.

Government of Canada — Group A streptococcal diseases (Streptococcus pyogenes)

PHAC — Pathogen Safety Data Sheet — Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Strep)

Alberta Public Health — Disease Management Guidelines — Streptococcal Disease Group A, Invasive

Laboratory diagnoses

Diagnoses for GAS are generally made by isolating GAS from a normally sterile site (e.g., blood, tissue from deep inside a wound, cerebrospinal fluid). However, diagnoses vary depending on the clinical syndrome.

All laboratories must submit confirmed GAS isolates to the National Centre for Streptococcus (NCS) in Alberta for M-protein serotyping.

Alberta Public Health — Disease Management Guidelines — Streptococcal Disease Group A, Invasive

Strep throat and scarlet fever

For group A strep pharyngitis and scarlet fever with pharyngitis, the gold standard test is a throat culture. A rapid antigen detection test (RADT) can also be used and has a high specificity for group A strep, however, its sensitivities vary when compared to throat culture tests.

CDC — For Clinicians — Pharyngitis (Strep Throat)

CDC — For Clinicians — Scarlet Fever

Rheumatic fever

Acute rheumatic fever does not have a specific diagnostic test. Due to the broad array of symptoms, differential diagnoses of acute rheumatic fever may include: lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, septic arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and more.

CDC — For Clinicians — Acute Rheumatic Fever

Nonbullous impetigo

Laboratory testing is not needed nor performed in clinical practice for nonbullous impetigo. To diagnose, doctors typically examine sores during a physical examination. It can be difficult, however, to reliably differentiate between streptococcal and staphylococcal nonbullous impetigo with a physical examination.

CDC — For Clinicians — Impetigo

Flesh-eating disease

Flesh-eating disease is diagnosed clinically based on a high level of suspicion for patients presenting with severe, profound pain at the site of a wound. However, when symptoms are non-specific (e.g., unexplained fever, pain, edema), it can be difficult to differentiate between flesh-eating disease and cellulitis.

Laboratory tests for flesh-eating disease may include:

- Complete blood counts (CBC), such as leukocytosis

- Platelets (thrombocytopenia)

- Eclectrolytes

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

- Glomerular filtration rate (GFR)

- C-reactive protein (CRP)

- International normalized ratio (INR)

- Liver function tests (LFTs)

- Electrocardiogram (ECG)

Gram stains may also be used to determine whether the disease is caused by GAS.

Emergency Care BC — Point-of-Care Emergency Clinical Summary — Necrotizing Fasciitis Diagnosis

BC Cancer — Lab Test Interpretation Table

CDC — For Clinicians — Type II Necrotizing Fasciitis

Cellulitis

Cellulitis is typically diagnosed clinically. Blood and other lab tests are usually not needed.

CDC — For Clinicians — Cellulitis

Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS)

In the early stages of STSS, differential diagnosis may be broad and include staphylococcal toxic shock or other viral or bacterial infections. Laboratory tests may include blood cultures (which are commonly, but not universally positive), blood tests, and urine tests.

Emergency Care BC — Point-of-Care Emergency Clinical Summary — Toxic Shock Syndrome — Diagnosis

CDC — For Clinicians — Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome

John Hopkins Medicine — Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS)

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN)

Diagnosis of PSGN includes evidence of preceding infection with GAS. Evidence can include having elevated streptococcal antibodies and the isolation of GAS from skin lesions or the throat.

CDC — For Clinicians — Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis

Prevention and control

One of the best ways to protect yourself from GAS is by washing your hands after coughing and sneezing, and before eating and preparing food.

To reduce the spread of GAS by respiratory droplets from the nose or throat, good respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette should also be practiced. This includes:

- Coughing or sneezing into a tissue and discarding the tissue after use

- Coughing or sneezing into the bend of your arm, not your hands, when tissues are unavailable

- Washing your hands often with soap and water, or using hand sanitizer, before touching your face (eyes, nose, and mouth)

Breaks in the skin, such as wounds or cuts, can provide an opportunity for S. pyogenes to enter the body. Therefore, it is also important to keep all breaks in the skin clean and to watch for signs of infection (i.e., swelling, redness, pain, drainage).

Government of Canada — Group A Streptococcal Diseases: Risks and Prevention

BCCDC — Streptococcal Disease, Invasive, Group A

Vaccination

There is currently no vaccine to prevent GAS infections; however, global plans for the first GAS vaccine have been in development.

In 2018, the World Health Organization released the GAS Vaccines Research and Development (R&D) roadmap and Preferred Product Characteristics (PPC) for the development of the first GAS vaccine. Advances on these developments can be found in the 2022 presentation, WHO expert review of Group A Streptococcus vaccines. In line with the WHO’s mission to develop GAS vaccines, the Strep A Vaccine Global Consortium (SAVAC) formed to further facilitate GAS vaccine development. SAVAC’s May 2024 forum report summarizes key barriers to industry investment for Strep A vaccine R&D, and recommendations to address these barriers. The forum also reviewed the latest progress for developing novel GAS vaccines, as described by Walkinshaw et al. (2023) These include four M protein-based candidates and four candidates designed around non-M protein antigens. Tables 1 and 2 list the eight vaccine candidates, their developers, and their stages of development as of February 2023 (the time of the article’s publication).

Table 1. M protein-based S. pyogenes vaccine developments

| Candidate | Developer | Current Development Phase | Antigens |

| StreptAnova (30-valent) | University of Tennessee and Vaxent | Phase 1a completed in 2020 | Four protein subunits comprising the N-terminal regions of M proteins from 30 S. pyogenes serotypes |

| J8/S2 combivax | Griffith University and the University of Alberta | Phase 1a ongoing | J8 peptide from the M protein C-terminus combined with a 20-mer B-cell epitope (K4S2) from SpyCEP |

| P*17/S2 combivax | Griffith University and the University of Alberta | Phase 1a ongoing | P*17 peptide from the M protein C-terminus combined with a 20-mer B-cell epitope (K4S2) from SpyCEP |

| StreptInCor | University of São Paulo | Preclinical | 55-amino acid sequence peptide from the M5 protein conserved regions (C2 and C3) |

Table 2. Non-M protein-based S. pyogenes vaccine developments

| Candidate | Developer | Current Development Phase | Antigens |

| Combo4 | GlaxoSmithKline and GVGH | Preclinical | SpyCEP, SLO and SpyAD recombinant proteins and native GAC conjugated to CRM197 carrier protein |

| VAX-A1 | Vaxcyte | Preclinical | SLO and SCPA recombinant proteins and modified GAC (Polyrhamnose) conjugated to SpyAD disease-specific carrier protein |

| Combo5 | University of Queensland | Preclinical | Trigger factor (TF), inactivated versions of arginine deiminase (ADI), SLO, SpyCEP and SCPA |

| TeeVax | University of Auckland | Preclinical | Multiple T-antigen domains from the pilus of the majority of S. pyogenes strains |

The GAS vaccine candidates are discussed in further detail in Walkinshaw et al. (2023)

The latest event for GAS vaccine development was held on May 20, 2025 at the 78th World Health Assembly by the International Vaccine Institute (IVI). A summary of the insights shared at the event can be found in their July 2025 report.

More information about SAVAC and its mission to advance global access to GAS vaccines is available in IVI’s 2024 short documentary below.

PHAC — Pathogen Safety Data Sheet — Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Strep)

WHO presentation — WHO expert review of Group A Streptococcus vaccines, September 30, 2022

Strep A Vaccine Global Consortium (SAVAC) — About

Walkinshaw et al. 2023 —The Streptococcus pyogenes vaccine landscape

Treatment

Treatment will vary depending on the type of GAS disease. In the absence of a GAS vaccine, antibiotics (e.g., penicillin, macrolide, or cephalosprin) are used to treat most GAS diseases. However, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) stewardship strategies should be considered to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use. For example, according to Choosing Wisely Canada, when treating group A pharyngitis, consider only using antibiotics in confirmed bacterial pharyngitis and delaying antibiotics while awaiting throat swab results. For more information on using antibiotics wisely, visit Choosing Wisely Canada.

PHAC — Pathogen Safety Data Sheet — Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Strep)

Epidemiology

General

iGAS diseases are a global cause of morbidity and mortality, but are more prevalent in populations who are living in overcrowded conditions or in socioeconomically disadvantaged regions. Globally, iGAS diseases are responsible for more than 500,000 deaths annually.

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, several countries witnessed an increase in iGAS. In December 2022, the World Health Organization reported an increase in iGAS cases and deaths across Europe (including France, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Sweden). Similarly, in December 2022, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a health advisory for a spike in pediatric iGAS cases.

PHAC — Pathogen Safety Data Sheet — Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Strep)

Canada

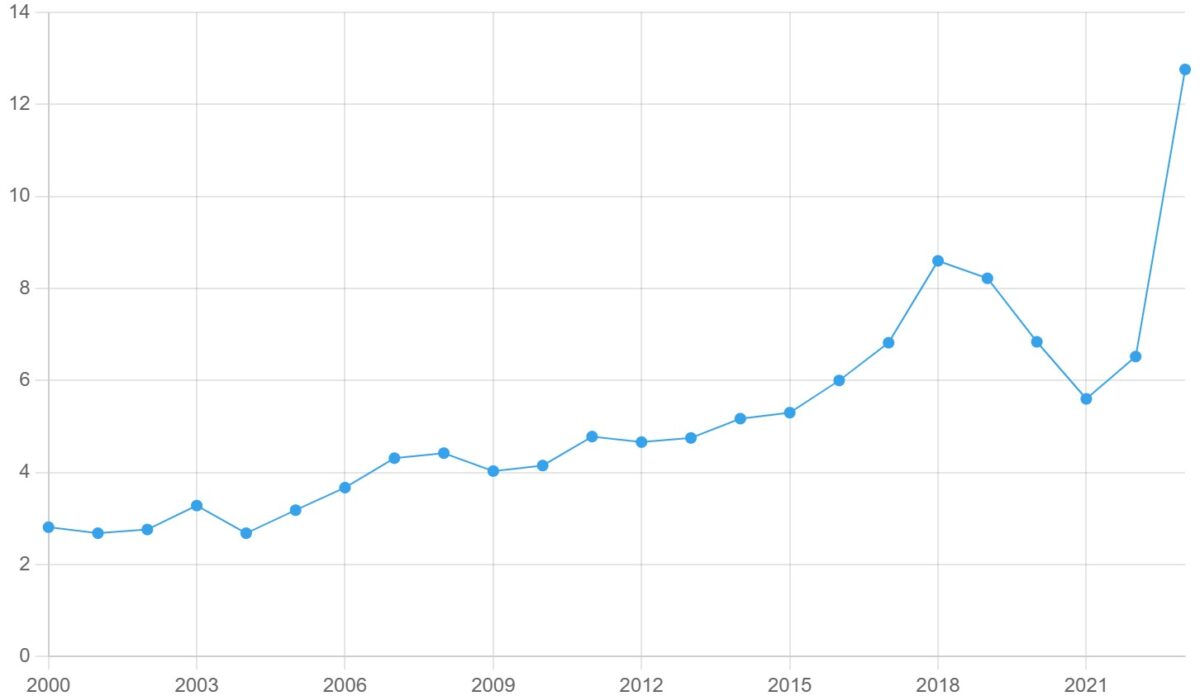

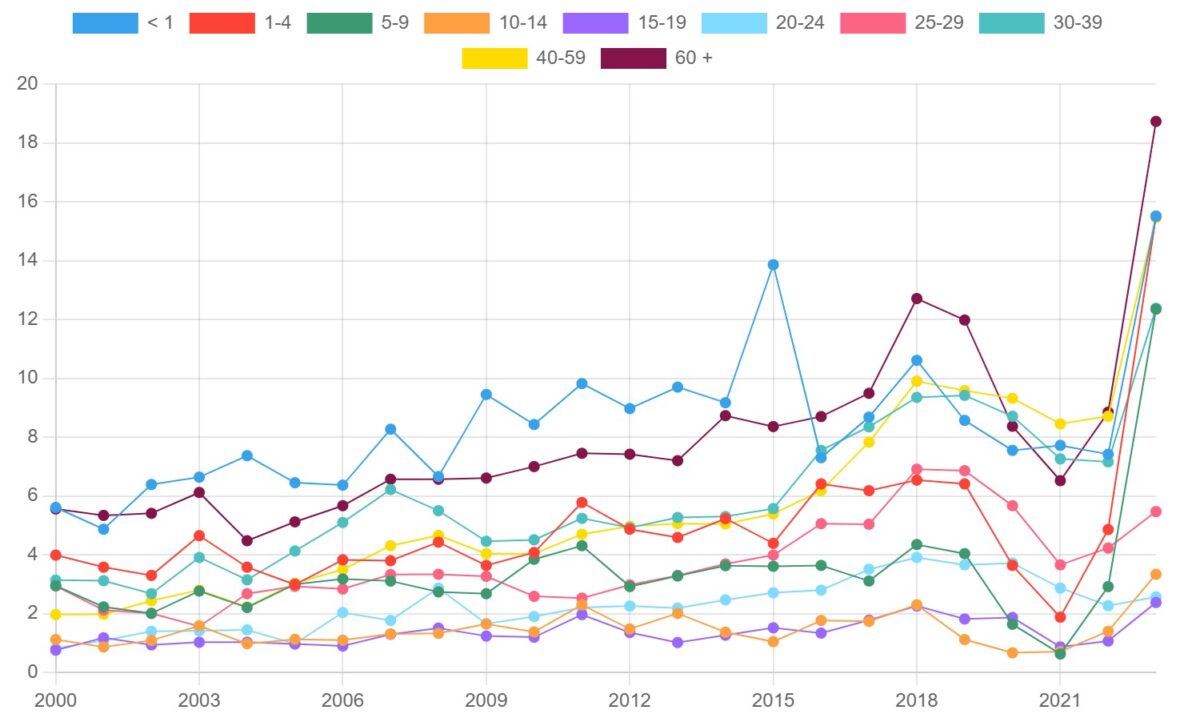

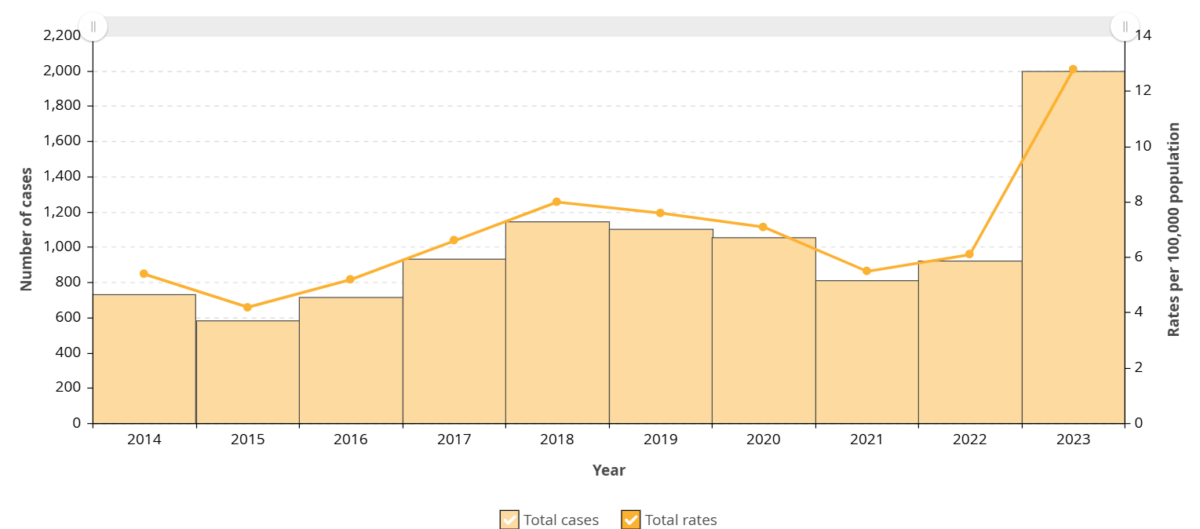

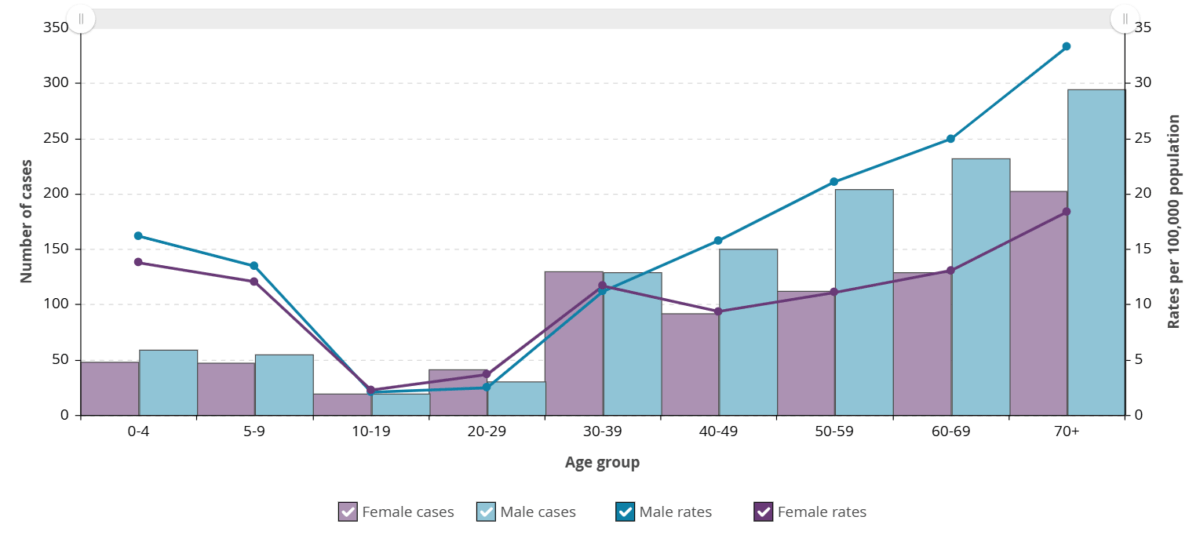

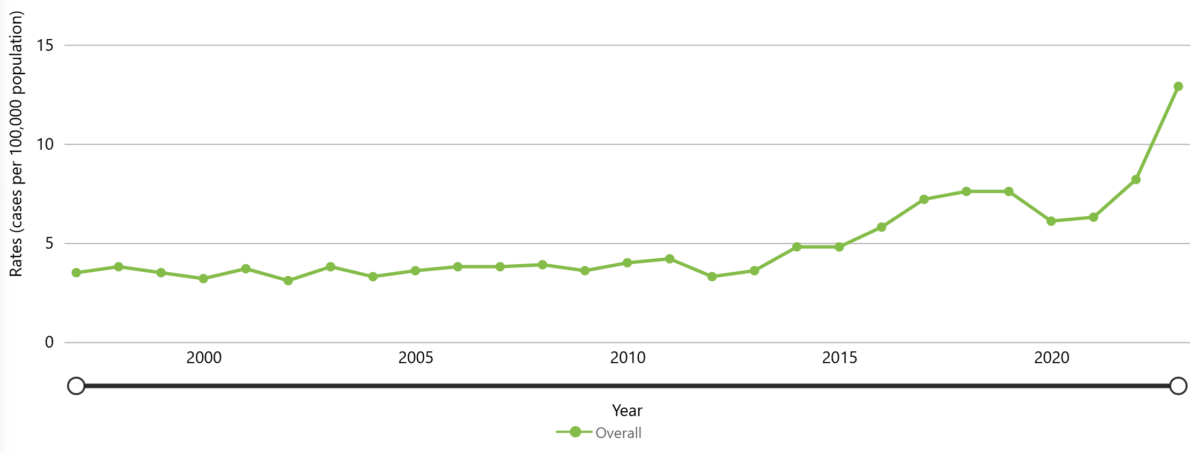

iGAS is endemic in Canada, with the average number of cases rising since 2000 (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. iGAS rate per 100,000 population in Canada, 2000-2023

Figure 2. iGAS rate per 100,000 population in Canada, by age group, 2000-2023

National iGAS data from the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS) is available up to 2023. In 2023, there was 4,929 cases of iGAS in Canada (12.76 iGAS cases per 100,000 people) – a record number for the country. The previous peak occurred in 2019 at roughly 3,200 cases.

The age groups most affected by iGAS in 2023 were adults over the age of 60 (18.73 cases per 100,000 population) followed by children under the age of four (15.51 cases per 100,000 population) and adults between the ages of 40 and 59 (15.46 cases per 100,000 population). Table 3 presents the iGAS incidence rates (per 100,000 population) and case counts for each age group, organized from highest to lowest iGAS incidence rates, for 2023.

Table 3. iGAS incidence rate and case counts in Canada by age group in 2023, sorted in descending order of incidence rate

| iGAS cases per 100,000 population | Number of reported cases | Age group (years) |

| 18.73 | 1,856 | 60+ |

| 15.51 | 278 | 0-4 |

| 15.46 | 1,511 | 40-59 |

| 12.38 | 693 | 30-39 |

| 12.35 | 251 | 5-9 |

| 5.47 | 153 | 25-29 |

| 3.34 | 70 | 10-14 |

| 2.57 | 64 | 20-24 |

| 2.38 | 51 | 15-19 |

Provincial and Territorial Data

The most up-to-date provincial iGAS rates and case counts for Manitoba, Alberta, British Columbia, and Ontario can be found on their respective provincial websites or dashboards. Table 4 presents iGAS incidence rates and case counts for Manitoba, Alberta, Ontario, and British Columbia from 2022 to 2024.

Table 4. iGAS rate per 100,00 population and case count for Manitoba, Alberta, British Columbia, and Ontario, 2022-2024

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||||

| Province | Rate of iGAS per 100,000 population | Number of reported cases | Rate of iGAS per 100,000 population | Number of reported cases | Rate of iGAS per 100,000 population | Number of reported cases |

| Manitoba | 11.8 | 168 | 19.2 | 279 | 21.9 | 326 |

| Alberta | 9.62 | 434 | 16.40 | 6.1 | N/A | N/A |

| British Columbia | 8.7 | 464 | 10.9 | 600 | N/A | N/A |

| Ontario | 6.1 | 922 | 12.8 | 1,997 | N/A | N/A |

According to the most recent literature on iGAS surveillance in Canada by Golden et al. (2024), provinces and regions of Canada submitted the following number of bacterial isolates of iGAS to the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) in Winnipeg for testing in 2022:

- Manitoba: 201 isolates

- Alberta: 522 isolates

- British Columbia: 425 isolates

- Ontario: 905 isolates

- Québec: 365 isolates

- Saskatchewan: 121 isolates

- Atlantic Canada (New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador): 80 isolates

- Northern Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut): 11 isolates.

Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System – Group A Streptococcal Disease, Invasive

Government of Canada — Group A Streptococcal diseases: For Health Professionals

Manitoba Health — Group A streptococcus (GAS)

Alberta Interactive Health Data Application — iGAS

British Columbia Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) — Communicable Disease Dashboard

Public Health Ontario — Group A Streptococcal Disease, Invasive (iGAS)

Golden et al., 2024. Invasive group A streptococcal disease surveillance in Canada, 2021–2022

Manitoba

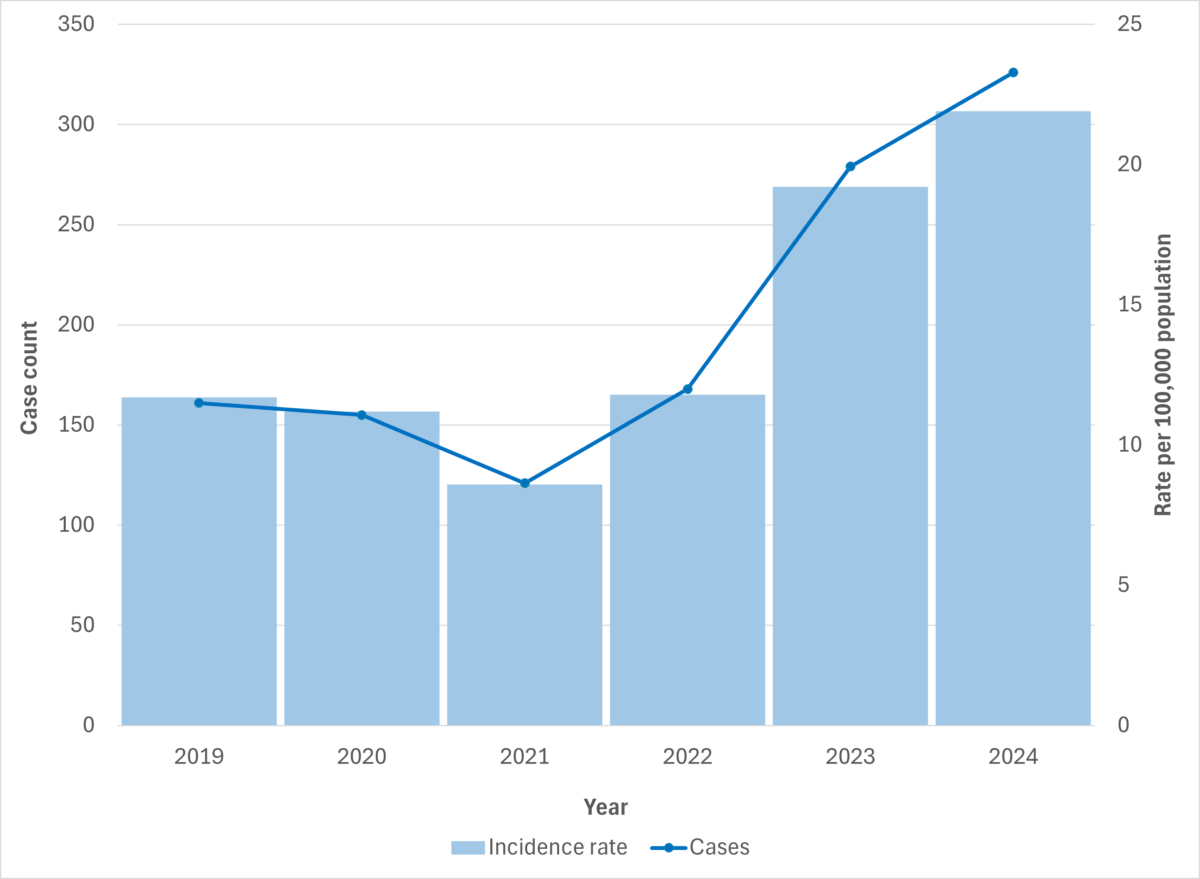

Figure 3. iGAS cases and incidence rate per 100,000 population in Manitoba, 2019-2024

Alberta

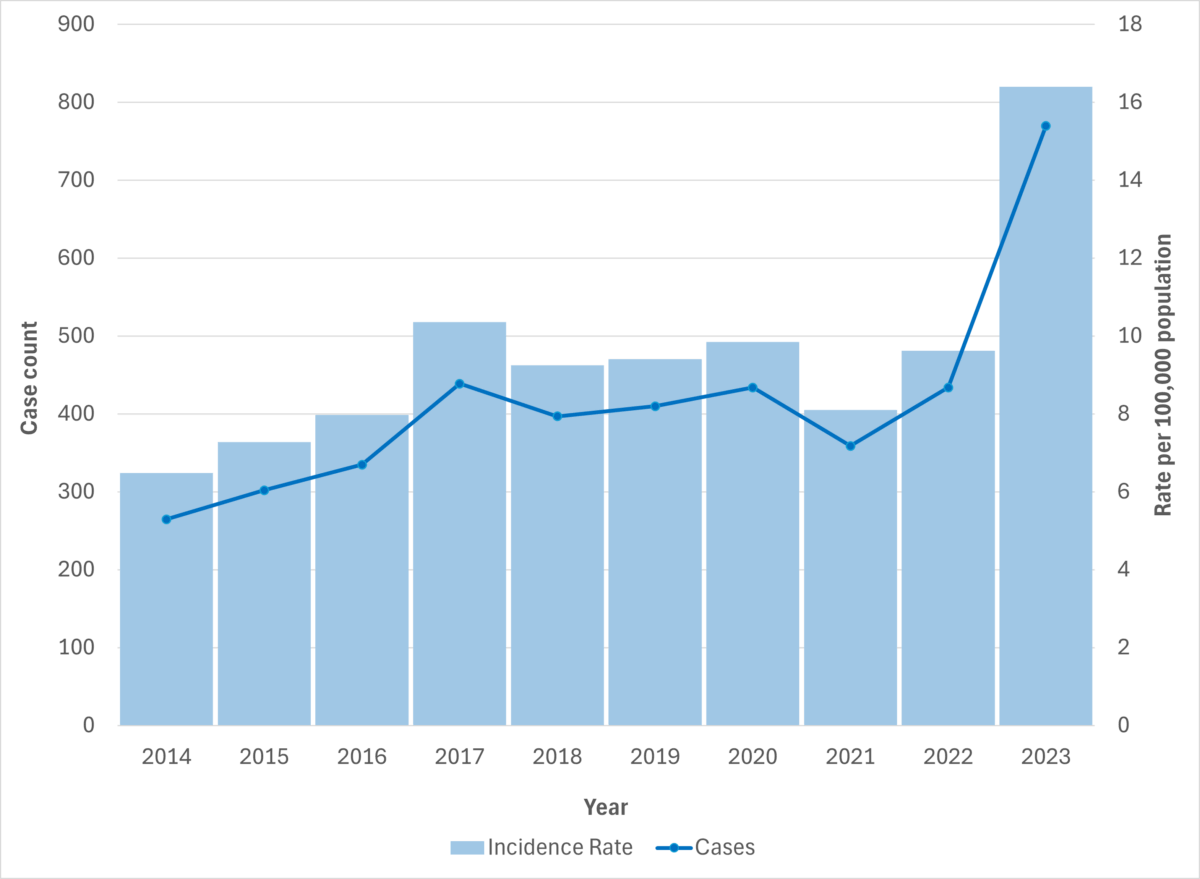

Figure 4. iGAS cases and incidence rate per 100,000 population in Alberta, 2014-2023

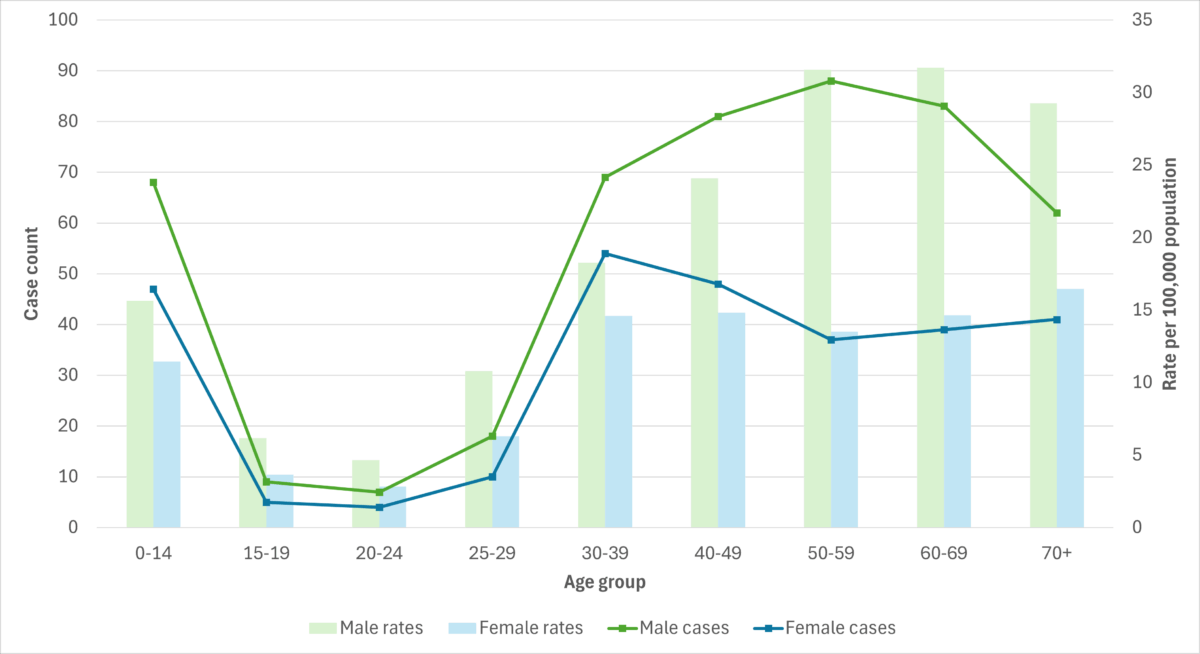

Figure 5. iGAS cases and incidence rate per 100,000 population in Alberta, by age group and sex, 2023

British Columbia

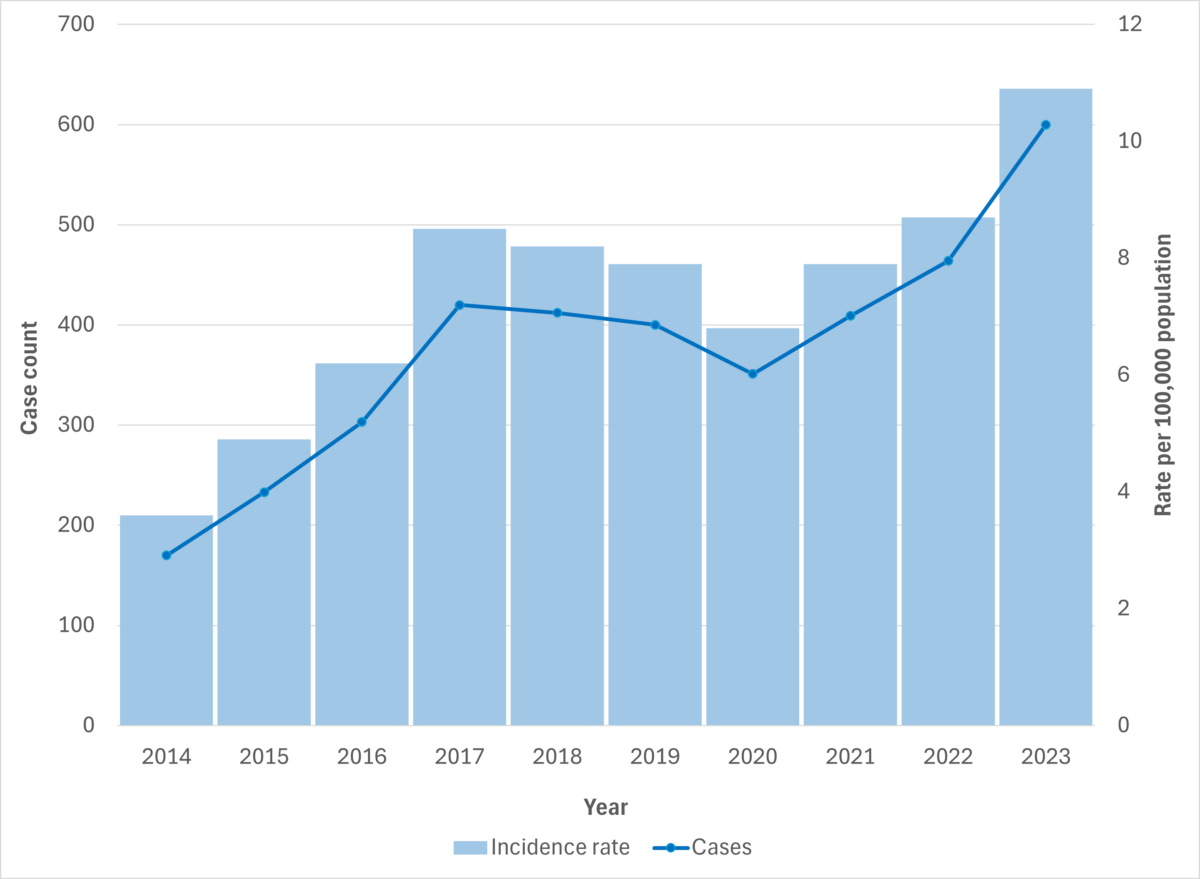

Figure 6. iGAS cases and incidence rate per 100,000 population in British Columbia, 2014-2023

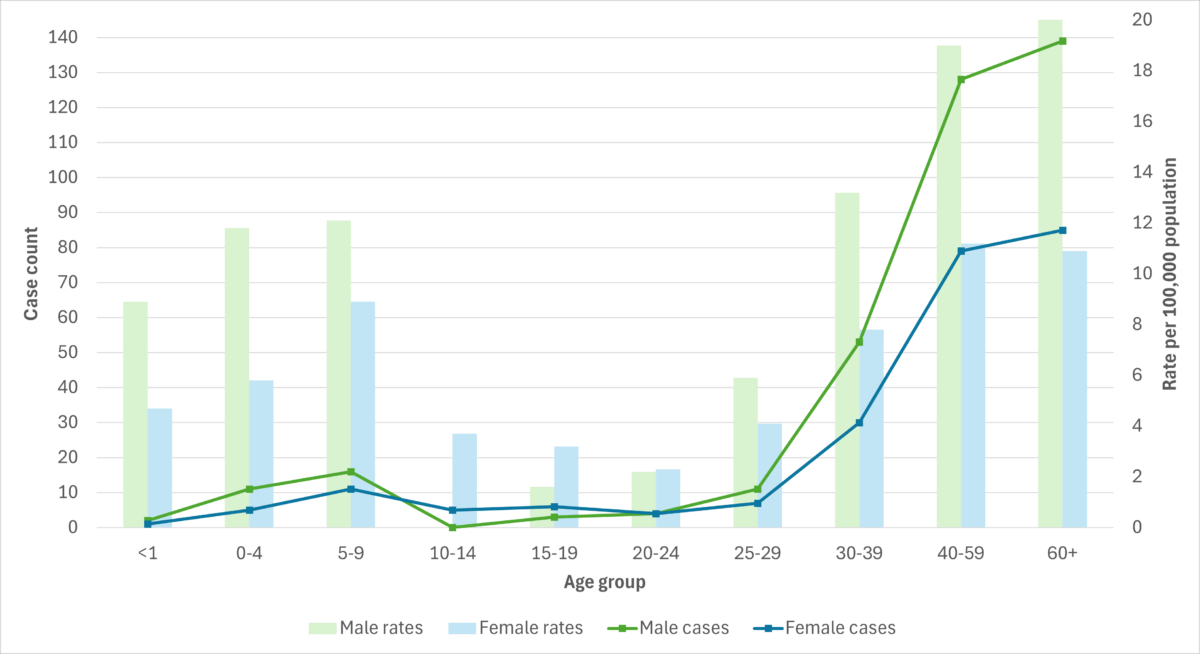

Figure 7. iGAS cases and incidence rate per 100,000 population in British Columbia, by age group and sex, 2023

Data for each health region in British Columbia is available on the BCCDC Communicable Disease Dashboard.

Ontario

Figure 8. iGAS cases and incidence rate per 100,000 population in Ontario, 2014-2023

Figure 9. iGAS cases and incidence rate per 100,000 population in Ontario, by age group and sex, 2023

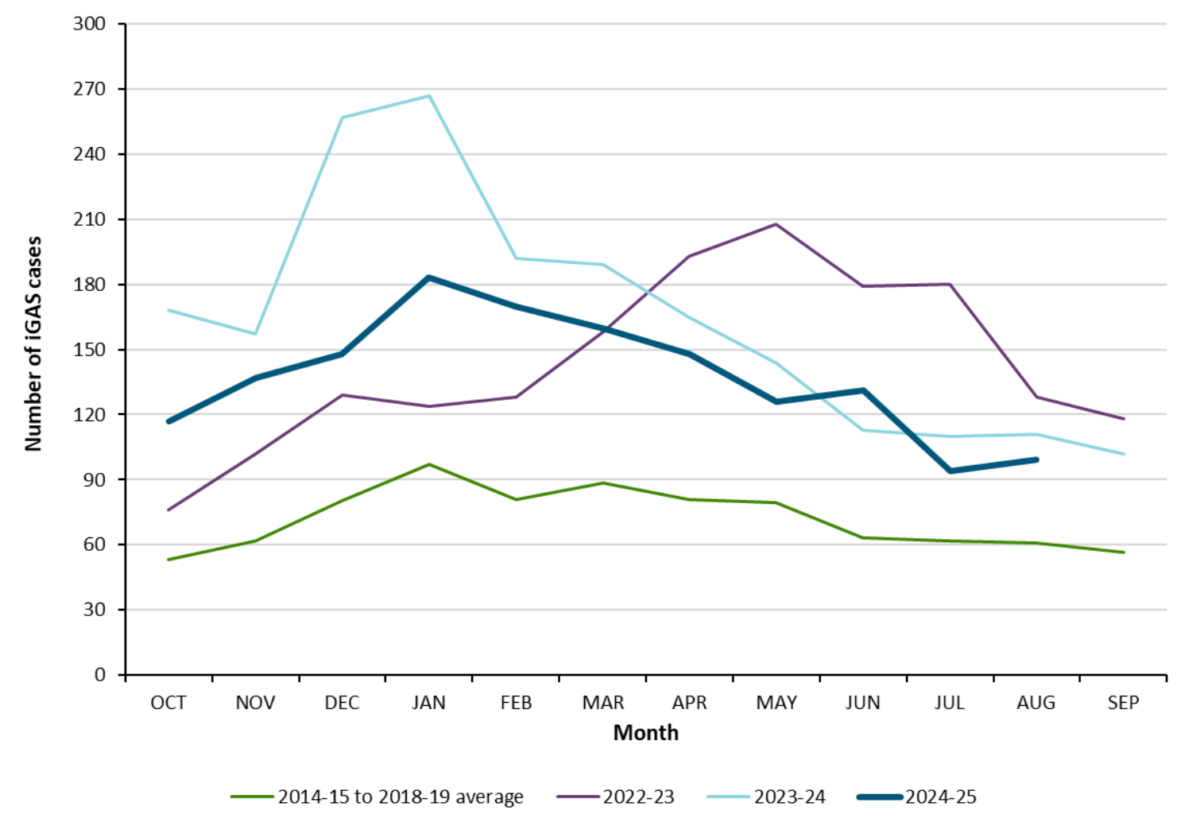

In Ontario, the number of iGAS cases and the incidence rate reported between October 1, 2024 and August 30, 2025 was lower, on average, than the 2023-2024 season. However, the total number of cases for the 2024-2025 time period was higher than the average of the five pre-pandemic seasons (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Confirmed iGAS case counts in Ontario by 2024-2025 season (1 October 2024 – 31 August, 2025) compared to pre-pandemic seasons (1 October 2014 – 30 September 2019).

Manitoba Health — Group A streptococcus (GAS)

Alberta Interactive Health Data Application — iGAS

BCCDC — Communicable Disease Dashboard

Public Health Ontario — Group A Streptococcal Disease, Invasive (iGAS)

United States

iGAS data from the CDC’s Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) Dashboard is available up to 2023.

The average number of iGAS cases has risen in the United States over the past decade, with 2023 data indicating a 20-year high in the number of serious infections caused by GAS. In 2023, the U.S. reported 43,100 cases of iGAS (12.9 cases per 100,000 population).

Figure 11. Rate per 100,000 reported cases of iGAS in the United States between 1997 to 2023

CDC — Group A Streptococcal (GAS) Disease — Surveillance

CDC — Bact Facts Interactive — Data Dashboard — Group A Streptococcus (GAS)

What is happening with current outbreaks of invasive Group A streptococcal disease?

iGAS data beyond 2023 is publicly available for Manitoba and Ontario.

In Manitoba, both iGAS cases and deaths increased in 2024 compared to 2023, with 326 cases (21.9 cases per 100,000 population) and 27 deaths reported in 2024, up from 279 cases (19.2 cases per 100,000) and 21 deaths in 2023. Between January 1 and July 8, 2025, 127 cases (8.5 cases per 100,000) and nine deaths were reported in the province.

In Ontario, iGAS cases and deaths were lower during the 2024–2025 season (October 1, 2024 to August 31, 2025) compared to the 2023–2024 season. In 2024–2025, 1,513 cases (9.3 cases per 100,000 population) and 158 deaths were reported, down from 1,873 cases (11.7 cases per 100,000) and 221 deaths in 2023–2024. This represents a 20.5% reduction in the incidence rate between the 2024-2025 and 2023-2024 seasons.

Manitoba Health — Group A streptococcus (GAS)

Invasive Group A Streptococcal (iGAS) Disease in Ontario: October 1, 2024 to August 31, 2025

What is the current risk for Canadians from Group A streptococcal disease?

Because GAS is commonly transmitted person-to-person by coughing or sneezing, transmission rates are higher in overcrowded and/or enclosed social settings, such as schools, nurseries, hospitals, homeless shelters, and residential care homes.

Risk factors for GAS infection have also been associated with:

- Underlying, chronic medical conditions including:

- Diabetes

- Lung disease

- Liver disease

- Heart disease

- Weakened immune systems caused by:

- Cancer treatments (radiation, chemotherapy)

- Disease (HIV infection, AIDS)

- Anti-injection drugs following organ or bone-marrow transplants

- Breaks in the skin including:

- Wounds

- Cuts

- Burns

- Open Sores

- Varicella infection

- Substance abuse, including use of injectable drugs

- Recent close contact with someone infected with GAS

Additionally, several studies have examined population groups that may be at higher risk of GAS infection. Other at-risk groups identified in the literature include:

- Pregnant persons, persons with postpartum status, and neonates

- Children under the age of 15 years

- Persons identifying as male

- Elderly

- People living in poor housing conditions (e.g., dampness, poor ventilation, poor house temperature).

- People exposed to:

- tobacco smoke

- biting insects

- skin injuries

Government of Canada — Group A Streptococcal diseases: For Health Professionals

What measures should be taken for a suspected Group A streptococcal disease case or contact?

Individuals suspected of having a GAS infection should seek medical care for testing and treatment immediately.

Close contacts of a person infected with iGAS should monitor for symptoms of iGAS and seek medical care if clinical manifestations develop. Close contacts can be defined as:

- Household contacts of a person infected with iGAS who have spent an average of at least 4 hours/day in the last 7 days or 20 hours/week with a person infected with iGAS

- Non-household persons who share the same bed or had sexual relations with a person infected with iGAS

- Persons who have made direct contact with oral or nasal secretions (e.g. mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, open mouth kissing) of a person infected with iGAS or unprotected direct contact with an open skin lesion of a person infected with iGAS

- Persons who inject drugs and have shared needles with a person infected with iGAS

Case Definitions

Confirmed Case

- Isolation of Group A Streptococcus pyogenes or deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)detection by nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT)from a normally sterile site (blood, cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid, peritoneal fluid, pericardial fluid, bone or joint fluid, or specimens taken during surgery) with or without evidence of severe invasive disease.

Probable Case

- Isolation of Group A Streptococcus from a non-sterile site (e.g., skin) in the absence of another identified etiology, with evidence of severe invasive disease.

Government of Canada — National Case Definition: Invasive Group A Streptococcal Disease, 2008

Identifying and Reporting

Confirmed cases of iGAS have been nationally notifiable in Canada since January 2000. Provinces and Territories are responsible for reporting confirmed cases of iGAS to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) through the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS). Surveillance is conducted through routine case-by-case notification to the federal level.

Provincial and territorial public health laboratories can receive assistance from the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) for GAS outbreak investigations upon request.

Government of Canada — National Case Definition: Invasive Group A Streptococcal Disease, 2008

Golden et al., 2022. Invasive Group A Streptococcal Disease Surveillance in Canada, 2020.