Are you looking for the PHAC guidance document for practitioners?

Data as of July 2024

NCCID Disease Debriefs provide Canadian public health practitioners and clinicians with up-to-date reviews of essential information on prominent infectious diseases for Canadian public health practice. While not a formal literature review, information is gathered from key sources including the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO) and peer-reviewed literature.

This disease debrief was prepared and updated by Signy Baragar. Questions, comments, and suggestions regarding this disease brief are most welcome and can be sent to nccid@manitoba.ca.

What are Disease Debriefs? To find out more about how information is collected, see our page dedicated to the Disease Debriefs.

Questions Addressed in this debrief:

- What are important characteristics of dengue?

- What is the current risk for Canadians from dengue?

- What is the prevalence of dengue in Canada?

- What measures should be taken for a suspected dengue case or contact?

What are important characteristics of dengue?

Characteristics and Causes

Dengue is a viral infection caused by the bite of infected Aedes mosquitoes (Ae. aegypti or Ae. albopictus). There are four serotypes of dengue virus (DENV): DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 or DENV-4. When a mosquito bites a human who has any one of the DENV serotypes, the mosquito becomes infected. The infected mosquito can then spread the virus to other humans through biting them.

Dengue is most often found in tropical and subtropical regions. However, mosquitoes carrying the virus may adapt to new environments due to climate change and the consequences of the 2023 El Niño phenomena increasing temperatures, rainfall, and humidity.

- World Health Organization (WHO) Dengue and Severe Dengue Fact Sheet

- WHO Dengue and Severe Dengue

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Dengue

- Messina, J.P., Brady, O.J., Golding, N. et al. The current and future global distribution and population at risk of dengue. Nat Microbiol 4, 1508–1515 (2019)

- WHO Dengue – Global Situation

Symptoms

About 1 in 4 people with dengue will get sick. In general, most people have no or mild symptoms and recover within one to two weeks.

Mild symptoms of dengue may be confused with other illnesses that cause flu-like symptoms. The most common symptom of dengue is a sudden onset of high fever (40°C/ 104°F) for three to five days. The fever is usually accompanied by at least two of the following symptoms:

- severe headache

- pain behind the eyes

- muscle, bone, or joint pains

- nausea, vomiting

- rash

- swollen glands

Severity and Complications

About 1 in 20 people infected with a dengue virus will experience complications and develop severe dengue. Severe dengue occurs when blood vessels become damaged and platelet levels drop. This can lead to internal bleeding, organ failure, and shock.

Individuals who are infected with dengue for a second time are at a greater risk of developing severe dengue.

Severe dengue, also known as dengue haemorrhagic fever, often comes 24-48 hours after a high fever has passed. Symptoms of severe dengue may include:

- persistent vomiting

- severe stomach pain

- bleeding from gums or nose

- blood in urine, stools, or vomit

- difficult or rapid breathing

- feeling tired, weak, restless, or irritable

- being very thirsty

- pale and cold skin

Severe dengue can be fatal within hours and requires immediate hospital care.

- Government of Canada – Dengue Fever

- WHO Dengue and Severe Dengue

- WHO Dengue and Severe Dengue – Q&A

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – Dengue Symptoms and Treatment

Transmission

Dengue has a human-to-mosquito-to-human transmission cycle. After a mosquito bites a person infected with a dengue virus, the virus replicates and spreads in the mosquito’s tissues and salivary glands. Approximately 8-12 days after ingesting the virus, the infected mosquito can then spread the virus to other humans by biting them. The infected mosquito can continue to transmit the virus for the rest of its lifetime.

The female Aedes aegypti (yellow fever) mosquito is the primary vector that carries and transmits the dengue virus to humans. The Aedes albopictus (tiger or forest mosquito) is a secondary vector for dengue in Asia.

Dengue does not spread directly from person-to-person except on rare occasions through blood transfusions or organ donations.

Prevention and Control

The best way to prevent dengue is by reducing the number of mosquito breeding sites. If the number of breeding sites is reduced, there will be fewer emerging adult mosquitoes to transmit the dengue virus.

The Aedes aegypti mosquitoes lay their eggs in water-filled containers and prefer to live in urban areas near humans. The eggs hatch when in contact with water.

To limit the number of adult mosquitoes emerging from the egg/larva/pupa stage, cover or properly discard water-filled containers. Any remaining water-filled containers should be emptied, cleaned, and scrubbed once a week to remove mosquito eggs.

Indoor breeding sites for Aedes aegypti mosquitoes can include:

- Bottles, plastic containers

- Water storage tanks (domestic drinking water, bathroom, etc.,)

- Flower pots

- Ant traps

Outdoor breeding sites can include:

- Discarded bottles, containers, tins

- Drums for filling water

- Boats, equipment

- Leaves of various plants

- Tree holes, potholes, and holes from construction sites

- Tree seeds

Personal and Household Protection

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes feed on humans during the day, especially early in the morning and in the evening before dusk. In regions at risk of dengue, it is important to:

- Wear clothes that reduce exposed skin as much as possible

- Apply insect repellent (containing DEET, IR3535, or Icaridin)

- Use a mosquito net if sleeping during the day (when Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are most active), ideally sprayed with insect repellent

- Use window and door screens

- Use household insecticide aerosols, vaporizers, or coils

Vaccines

The first dengue vaccine (Dengvaxia®) was licensed in Mexico in 2015 for people aged 9 to 45 years. It is now licensed in 20 countries for individuals living in areas where dengue is endemic. The dengue vaccine is not approved for use in Canada.

The World Health Organization recommends only giving Dengvaxia® to people who previously had dengue.

- Caring for Kids New to Canada – Dengue

- World Health Organization – Vaccines and immunization: Dengue

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – Dengue Vaccine

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for dengue.

Acetaminophen (paracetamol) is often used for treating fever and pain symptoms. It is not recommended to take aspirin, ibuprofen, or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as they can increase the risk of bleeding.

Patients with symptoms of severe dengue are advised to go to a hospital immediately. Severe dengue is a medical emergency.

Epidemiology

Regional Overview

General

Almost half of the world’s population live in areas where there is a risk of contracting dengue. Dengue is most common in urban and semi-urban areas in tropical and subtropical regions and is currently endemic in 90 countries in five of the six World Health Organization (WHO) Regions: the Americas, Africa, Eastern Mediterranean, South-East Asia, and Western Pacific. Dengue is not endemic in the WHO European Region, however, has been spreading to new areas in Europe, as well as to new areas of South America and the Eastern Mediterranean.

As of June 28, 2024, the annual number of dengue cases peaked to a historical high at over 10 million cases in 2024 worldwide; the majority, of which, were reported by PAHO in the Region of the Americas.

As the climate crisis drives warming temperatures and shifts in rainfall patterns, dengue is suspected to become endemic in the southern United States of America, southern Europe, and parts of Africa in the next 10 years.

- World Health Organization – Dengue and Severe Dengue – April 23, 2024

- World Health Organization – Dengue – Global Situation – May 30, 2024

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Weekly Bulletin – Communicable Disease Threats Report – Week 26 (June 22 – 28, 2024)

- Reuters – Dengue will ‘take off’ in southern Europe, US, Africa this decade, WHO scientist says

Region of the Americas

Current Situation (Data as of June 15, 2024)

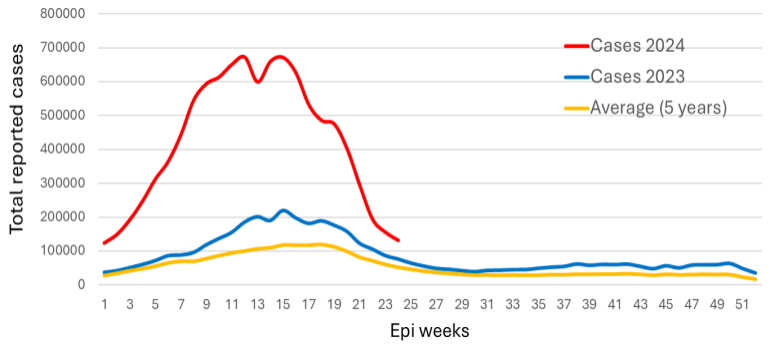

Between January 1 – June 15, 2024, the Region of the Americas reported a total of 10,141,300 suspected cases of dengue, representing a 232% increase compared to the same period in 2023 and a 421% increase compared to the last 5-year average (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Total number of suspected dengue cases in the Region of the Americas in 2023 – 2024 (until EW 24) and the last 5-year average.

Note. Reproduced from the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Epidemiological Report on Dengue, Epidemiological Week 24, 2024 (June 9 – 15, 2024). Data entered into the Health Information Platform for the Americas (PLISA, PAHO/WHO) by the Ministries and Institutes of Health of the countries and territories of the Region. Accessed July 8, 2024.

As of the epidemiological week (EW) 24 in 2024 (June 9 – 15, 2024), there were a total of 131,447 new suspected cases of dengue reported to PAHO (Table 1). The highest numbers of new cases were reported in Brazil (98,848 cases), followed by Colombia (9,789 cases) and Mexico (7,392 cases).

Table 1. Dengue cases reported to PAHO in EW 24, 2024, by countries and territories of the Americas.

Note. Reproduced from the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Epidemiological Report on Dengue, Epidemiological Week 24, 2024 (June 9 – 15, 2024). Data entered into the Health Information Platform for the Americas (PLISA, PAHO/WHO) by the Ministries and Institutes of Health of the countries and territories of the Region. Accessed July 8, 2024.

*Easter Island (Rapa Nui)

- PAHO/WHO – Epidemiological Report on Dengue, Epidemiological Week 24, 2024 (June 9 – 15, 2024).

- PAHO/WHO – Dengue – Accessed July 8, 2024

Cumulative Data (1980 – 2024)

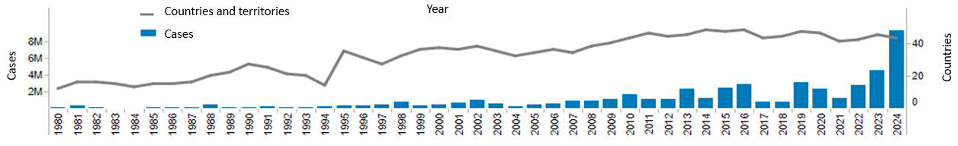

The number of dengue cases reported in the Region of the Americas has, on average, increased considerably since the beginning of the 1980s (Figure 2). The Region of the Americas experienced a marked geographical spread of dengue during the 1980s due to the expansion and reintroduction of different dengue serotypes to countries that had not previously had dengue or had not had the disease for several decades. In the four subsequent decades, cases reported to PAHO increased from approximately 65,000 cases in 1980 to 3.1 million in 2019. While there was a slight decline in cases during the COVID-19 pandemic between the years 2020 – 2022, cases markedly increased to a record-breaking 10.1 million as of June 15, 2024.

Figure 2. Trend of dengue cases and countries reporting on dengue in the Region of the Americas, 1980 to 2024.

Note. Figure reproduced from PAHO’s June 18, 2024 Epidemiological Update, “Increase in dengue cases in the Region of the Americas.”

- PAHO/WHO – Epidemiological Update – Increase in Dengue Cases in the Region of the Americas – 18 June 2024

- Dick et al. (2012) – The History of Dengue Outbreaks in the Americas

Serotypes

All four dengue serotypes (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4) circulate in the Region of the Americas. As of June 15, 2024, simultaneous co-circulation of all four serotypes was reported in Brazil, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Panama. For more information on the distribution of serotypes by countries and territories in the Region of the Americas, please visit PAHO/WHO – Epidemiological Report on Dengue, Epidemiological Week 24, 2024 (June 9 – 15, 2024).

- PAHO/WHO – Epidemiological Update – Increase in Dengue Cases in the Region of the Americas – 18 June 2024

- PAHO/WHO – Epidemiological Report on Dengue, Epidemiological Week 23, 2024 (June 2 – 8, 2024).

United States of America

Current Situation (Data as of July 2, 2024)

Dengue is currently endemic in six territories and freely associated states in the United States: Puerto Rico, American Samoa, the U.S. Virgin Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau. Transmission in the rest of the United States has been limited to small outbreaks or sporadic cases, particularly in Florida, Hawaii, and Texas.

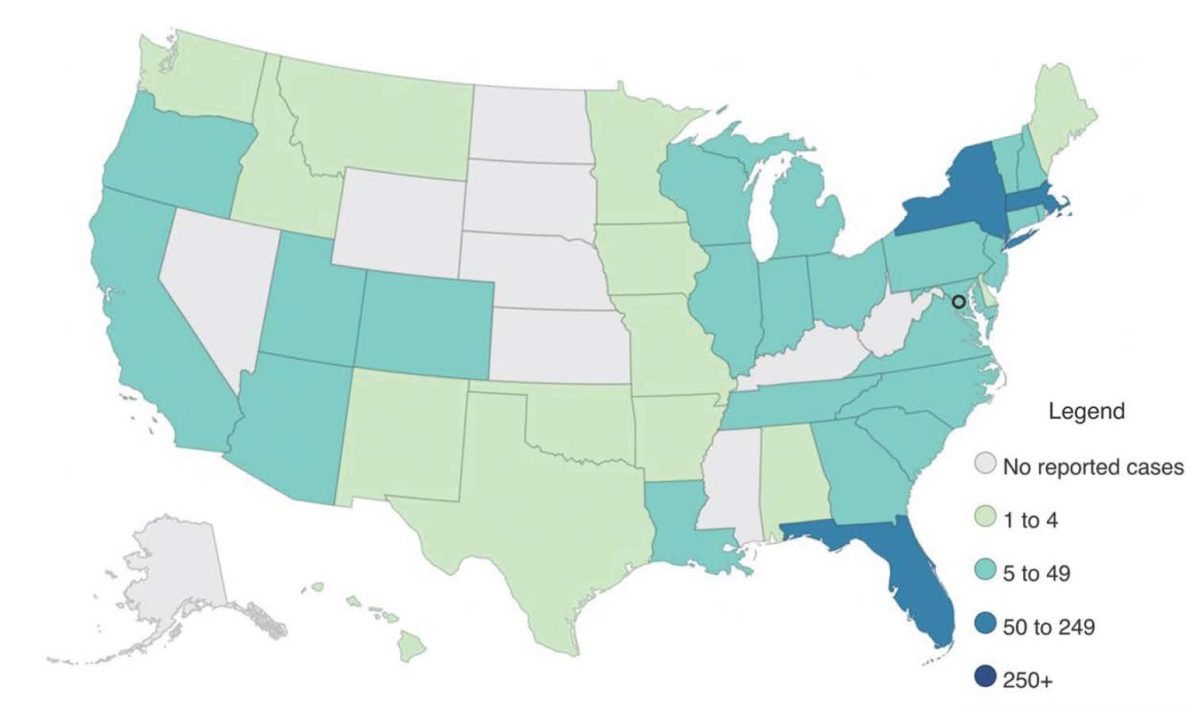

From January 1 to July 2, 2024, the United States reported 2,391 dengue cases across 45 jurisdictions, of which, 1,597 were acquired locally and 794 were associated with travelling. Of the 1,597 locally acquired cases in 2024, the majority were reported in Puerto Rico (1,580 cases) followed by Virgin Islands (10 cases) and Florida (7 cases). Due to the high number of cases reported in Puerto Rico, public health authorities declared a public health emergency for Puerto Rico in March 2024. The distribution of cases as of July 2, 2024, is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Total number of locally acquired and travel associated dengue cases in the United States by state and territory, as of July 2, 2024.

Note. Figure adapted from the CDC – Current Year Data (2024) – Dengue. Accessed July 8, 2024.

- CDC – Current Year Data (2024) – Dengue – Accessed July 9, 2024

- CDC – Historic Data (2010 – 2023) – Dengue – Accessed July 9, 2024

- CDC Health Advisory – Increased Risk of Dengue Virus Infections in the United States – 25 June 2024

Cumulative Data (2014-2024)

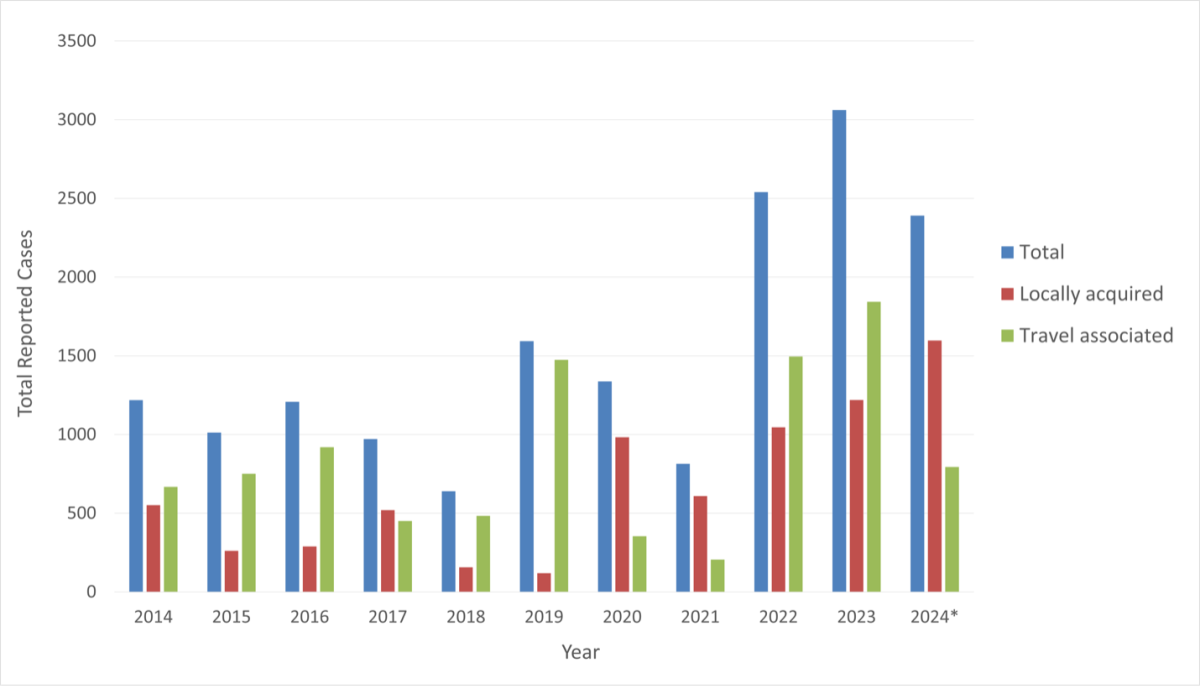

In the past decade, the incidence of dengue in the United States has increased, on average, from 1,218 cases in 2014 to a peak of 3,062 cases in 2023 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Total reported dengue cases in the United States with travel status, 2014-2024

Note. Data retrieved from the CDC – Current Year Data (2024) – Dengue and CDC – Historic Data (2010 – 2023) – Dengue on July 9, 2024.

* Includes data from January 1 – July 2, 2024

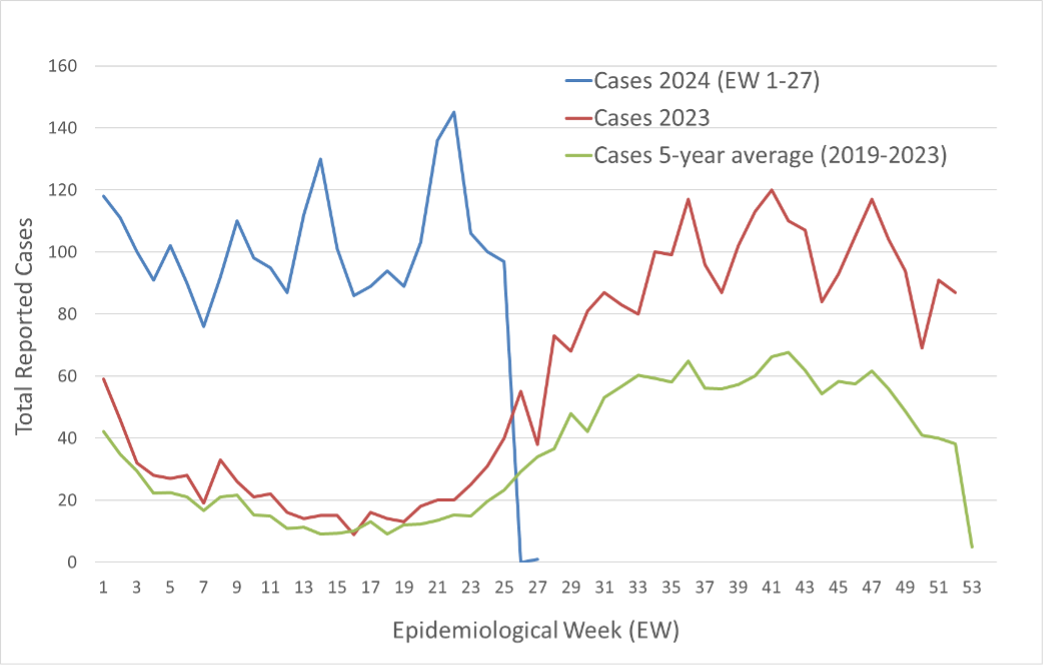

From January to July 2024 (EW 1-27), the United States reported 2,391 dengue cases which represents an increase of 241% compared to the same time period in 2023 and a 371% increase compared to the same time period in the previous 5-year average (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Total number of reported dengue cases in the United States in 2023 – 2024 (until EW 27) and the last 5-year average.

Note. Data retrieved from the CDC – Current Year Data (2024) – Dengue and CDC – Historic Data (2010 – 2023) – Dengue on July 9, 2024.

Canada

In Canada, there have been no locally acquired dengue cases reported. All reported cases of dengue in Canada have been among travellers returning from areas with dengue.

- Public Health Agency of Canada – Dengue Fever – Risks

- Public Health Agency of Canada – Dengue Fever – Surveillance

Incubation Period

The average incubation period begins 4–10 days after infection and last for 2–7 days.

What is the current risk for Canadians from dengue?

The risk of contracting dengue in Canada is low. All travelers are at risk of dengue if travelling to areas where dengue is endemic.

What is the prevalence of dengue in Canada?

In Canada, approximately 200-300 cases of dengue are imported each year. All cases have been among travellers returning from countries where dengue is present.

- Public Health Agency of Canada – Dengue Fever – Risks

- Public Health Agency of Canada – Dengue Fever – Surveillance

What measures should be taken for a suspected dengue case or contact?

With the global incidence of dengue increasing, healthcare providers are encouraged to have increased suspicion for dengue among patients with fever who have recently traveled outside of Canada to areas with frequent or continuous dengue transmission within 14 days before illness onset.

Individuals are advised to see a healthcare provider if symptoms of dengue develop while travelling or after return to Canada. A healthcare provider will make an accurate diagnosis based on travel history, symptoms, and laboratory testing.

Case Definition

Identifying and Reporting

Dengue is not a nationally notifiable disease in Canada.

Laboratory Testing

The National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) of PHAC provides four reference diagnostic services for dengue: molecular testing by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR); serological testing of both dengue-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA); and serological testing of antibodies by Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test (PRNT)*. All four testing methods require serum specimens, although, molecular testing can also be performed on plasma or cerebral spinal fluid (CSF).

The testing turnaround time at NML is 21 calendar days for RT-PCR and 14 calendar days for dengue-specific IgM/IgG ELISA. For PRNT, the testing turnaround time is 21 calendar days after the completion of preliminary ELISA testing.

*Testing by PRNT at NML is only performed for reactive (positive) results from dengue-specific IgM/IgG ELISA. Non-reactive (negative) ELISA samples will not be tested by PRNT.

- NML Guide to Services – Arbovirus, Rabies, Rickettsia and Related Zoonotic Diseases Laboratory Details

- NML Molecular Detection of Dengue Virus by Reverse Transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR)

- NML Detection of IgM Antibodies Directed Towards Dengue Virus by ELISA

- NML Detection of IgG Antibodies Directed Towards Dengue Virus by ELISA

- NML Detection of Antibodies Directed Towards Dengue Virus by PRNT

Laboratory Interpretation

Positive RT-PCR test results are indicative of a current dengue diagnosis. RT-PCR results are classified as positive if any of the four dengue serotype targets are detected in their respective singleplex assays and if the cycle threshold (Ct) value falls within the pre-established target for the specific assay/serotype.

Past or present exposure to dengue is indicated by the detection of IgG antibodies in a dengue-specific IgG antibody test. A dengue case is considered “confirmed” if there is a fourfold or greater rise in neutralizing antibody tire, or seroconversion in paired sera.

Detection of IgM antibodies is indicative of exposure to dengue at an undetermined time. It is important to note, however, that detection of IgM alone is not sufficient for confirmation of acute infection as IgM antibodies may remain in serum for one year or longer following exposure to the virus.