Updated March 8, 2024

NCCID Disease Debriefs provide Canadian public health practitioners and clinicians with up-to-date reviews of essential information on prominent infectious diseases for Canadian public health practice. While not a formal literature review, information is gathered from key sources including the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the World Health Organization (WHO) and peer-reviewed literature.

The purpose of this Disease Debrief is to provide public health personnel in practice and in policy with a quick reference to congenital syphilis and to encourage practitioners to test for syphilis among pregnant individuals at risk of infection. For more information regarding syphilis, see our Syphilis Disease Debrief.

This disease debrief was prepared by Signy Baragar. Questions, comments and suggestions regarding this debrief are most welcome and can be sent to nccid@manitoba.ca

What are Disease Debriefs? To find out more about how information is collected, see our page dedicated to the Disease Debriefs.

Questions Addressed in this debrief:

- What are important characteristics of congenital syphilis?

- What is happening with current outbreaks of congenital syphilis?

- What is the current risk for Canadians from congenital syphilis?

- What measures should be taken for a suspected congenital syphilis or contact?

What are important characteristics of congenital syphilis?

Cause

Congenital syphilis is caused by the spirochaete bacterium Treponema pallidum. It is transmitted to the baby mainly during pregnancy by an infected mother, although transmission can also occur via contact with active genital lesions in the mother at the time of delivery. If untreated, maternal syphilis can cause miscarriage, pre-term birth, stillbirth, neonatal death, or clinical manifestations of congenital syphilis in the newborn.

The stage of maternal infection affects the likelihood of transmission to the fetus. Syphilis contracted near term during pregnancy poses the highest risk of transmission to the fetus. The risk of vertical transmission for primary (i.e., chancre) or secondary (i.e., rash) maternal syphilis cases is between 70 to 100%, and 40% in the early latent phase. Women who become infected in the first year postpartum may also infect their infants via breastfeeding if lesions are present on the breasts.

- Government of Canada – Syphilis in Canada: Technical Report on Epidemiological Trends, Determinants and Interventions

- Current trends in congenital syphilis

- National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) – Congenital syphilis

- Congenital syphilis: A Guide to Diagnosis and Management

Signs and Symptoms

A pregnant woman infected with syphilis may have no symptoms. If symptoms are present, they can include chancres on the genitals or mouth, a rash, fever and swollen glands. When a mother with syphilis passes the infection on to their baby during pregnancy or childbirth, congenital syphilis can occur.

Congenital syphilis infections can be asymptomatic or symptomatic, with most infants presenting with no symptoms at the time of delivery. Early congenital syphilis occurs within the first two years of life with symptoms typically appearing between three to fourteen weeks of age. Clinical manifestations can include, but are not limited to:

| Nose and throat issues • rhinitis (“snuffles”) • laryngitis with hoarseness or aphonic cry | Gastro-intestinal issues • hepatomegaly • jaundice |

| Mucocutaneous lesions • skin rash with desquamation | Neurosyphilis |

| Skeletal problems • metaphyseal osteochondritis • epiphysitis • diaphyseal periostitis | Ocular abnormalities • chorioretinitis and pigmentary chorioretinopathy • glaucoma • cataracts • interstitial keratitis • optic neuritis |

| Hematologic issues • anemia • thrombocytopenia |

- NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Bureau of Sexually Transmitted Infections & NYC STD Prevention Training Center (March 2019): The Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Syphilis: An Update and Review

- Government of Canada congenital syphilis Fact Sheet

- National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) – Congenital syphilis

Severity and Complications

Adverse pregnancy outcomes are most severe in primary (i.e., chancre) or secondary (i.e., rash) maternal syphilis cases. If untreated, research suggests that approximately 76.8% of maternal syphilis cases will result in adverse pregnancy outcomes including a 36% risk of congenital syphilis, 23.2% risk of preterm birth, 23.4% risk of low birth weight, 26.4% risk of still birth or early fetal loss, 16.2% risk of neonatal death, and 14.9% risk of miscarriage.

Without treatment, symptomatic or asymptomatic infants and children may develop late-stage manifestations of untreated congenital syphilis. Late congenital syphilis symptoms typically present after two to five years and can remain undiagnosed in adulthood. Late-stage clinical manifestations can include:

| Facial, dental, and skeletal malformations • frontal bossing • saddle nose deformity • rhagades • anterior bowing of shins • clutton’s joints | Dental malfunctions • Hutchinson’s teeth • mulberry molars |

| Hematologic issues • hemoglobinuria | Neurologic complications • intellectual disability • hydrocephalus • seizures • cranial nerve palsies • paresis |

| Auditory issues • hearing loss | Ocular abnormalities • interstitial keratitis • glaucoma • corneal scaring • optic atrophy |

- NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Bureau of Sexually Transmitted Infections & NYC STD Prevention Training Center (March 2019): The Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Syphilis: An Update and Review

- Government of Canada congenital syphilis Fact Sheet

- National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) – Congenital syphilis

Transmission

Congenital syphilis is most commonly transmitted in utero; however, transmission can also occur during delivery by direct contact with an active genital lesion in the mother.

T. pallidum can cross the placenta and infect the fetus as early as the ninth gestational week and throughout pregnancy. The risk of transmission is highest in pregnant people who acquire syphilis near term; risk is also high during the primary and secondary stages of syphilis. For example, the risk of transmission for mothers with untreated primary or secondary syphilis during pregnancy is between 70% to 100%. For early latent syphilis, the risk is 40% and for late latent syphilis, the risk of transmission is less than 10%. Transmission can also occur from maternal syphilis cases contracted during the first year after childbirth.

- Government of Canada – Syphilis Guide: Risk Factors and Clinical Manifestation

- Canadian Paediatric Society – Congenital syphilis: no longer just of historic interest

Prevention and Control

Preventative measures such as practicing safer sex and reducing the number of sexual partners reduces the risk of contracting syphilis during pregnancy.

Routine syphilis screening is particularly important for the prevention of congenital syphilis. Screening is recommended for all pregnant people as part of standard prenatal care, and mothers at higher risk should be screened multiple times. Women at high risk of acquiring syphilis may be less likely to receive standard prenatal care; for this reason, screening pregnant women in emergency departments is also recommended.

Vaccines

There is no vaccine for the prevention of congenital syphilis.

Testing

Congenital syphilis can be prevented by testing and diagnosing syphilis early in women, prior to or during a pregnancy. The Public Health Agency of Canada recommends that all pregnant women be screened for syphilis at the first prenatal visit and at delivery. For women with an increased risk of acquiring syphilis, screening should be repeated at 28 to 32 gestational weeks. Alternatively, pregnant women residing in a geographic area with a high prevalence of syphilis or who are at high risk of reinfection should be screened monthly.

All neonates should be evaluated for presumed congenital syphilis if they were born to mothers in the following categories:

- Mothers with untreated syphilis at the time of delivery

- Mothers treated for syphilis within 4 weeks of delivery

- Mothers treated for syphilis during pregnancy without penicillin

- Mothers treated for syphilis prior to pregnancy with insufficient serologic follow-up to ensure response to treatment

- Mothers with evidence of reinfection or relapse post treatment (e.g., fourfold increase in titer)

- Mothers who do not demonstrate an adequate response (fourfold decrease in titer) despite appropriate penicillin treatment

- Mothers without a well-documented history of syphilis treatment

Syphilis serological results for a maternal/birthing parent and newborn may initially present as negative if syphilis is acquired in the maternal/birthing parent close to delivery. It is also possible that serologic tests may be negative during pregnancy with symptoms not apparent in the newborn until 3-14 weeks of age. Since most infected infants are asymptomatic at birth, it is critical that neonates are not discharged from hospital without confirmation that either the newborn or mother received appropriate serological testing.

- Government of Canada – Syphilis Guide: Screening and Diagnostic Testing

- Government of Canada – Syphilis in Canada: Technical Report on Epidemiological Trends, Determinants and Interventions

- PHAC – National case definition: Congenital syphilis (January 2024)

Treatment

Maternal syphilis

Treatment of the mother during pregnancy can dramatically reduce the risk of congenital syphilis. Fetal infection can usually be prevented if the mother receives adequate treatment before sixteen weeks gestation.

Adequate maternal treatment is a penicillin-based regimen initiated at least 1 month prior to delivery. Treatment schedules during pregnancy depend on the stage of maternal syphilis and the presence of neurosyphilis or ocular syphilis.

Treatment schedules recommended by the 2015 CDC STD Treatment Guidelines and Government of Canada Syphilis Guide are shown below:

| Diagnosis | Treatment |

| Primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis (<1 year) | Benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units intramuscularly in a single dose OR Benzathine penicillin-LAG 2.4 million units intramuscularly in a single dose weekly for two doses |

| Late latent syphilis (<1 year), latent syphilis of unknown duration, tertiary | Benzathine penicillin G, 7.2 million units total, administered as 3 doses of 2.4 million units intramuscularly each at 1-week intervals |

| Neurosyphilis and Ocular Syphilis | Aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 18-24 million units per day, administered as 3-4 million units intravenously every 4 hours or by continuous infusion for 10-14 days Alternative Regimen: Procaine penicillin, 2.4 million units intramuscularly daily in addition to probenecid 500 mg orally four times daily, both for 10–14 days |

Clinical and serologic evaluation of patients should occur at 6 months and 12 months followingadequate treatment for primary or secondary syphilis. Follow-up tests with at least a fourfold decline in titer after initiation of treatment are defined as an appropriate response. Mothers in whom symptoms continue to persist or reinfection occurs with a sustained fourfold increase in titer are recommended for re-treatment consisting of weekly injections of 2.4 million units intramuscularly benzathine penicillin for 3 weeks, in addition to re-evaluation for HIV infection.

In cases of latent syphilis, a gradual decline in titers may be seen and a low positive titer may persist. Quantitative nontreponemal test titer should be repeated at 6, 12, and 24 months.

- CDC Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2021

- Government of Canada – Syphilis guide: Treatment and follow-up

Child (congenital) syphilis

Neonates born to mothers with reactive nontreponemal test results should be examined for evidence of congenital syphilis and receive the same type of quantitative nontreponemal serologic test as the mother. The CDC recommends evaluation and treatment guidelines for the following scenarios:

Scenario 1: Confirmed Proven or Highly Probable Congenital Syphilis

Any neonate with:

- an abnormal physical examination that is consistent with congenital syphilis;

- a serum quantitative nontreponemal serologic titer that is fourfold (or greater) higher than the mother’s titer at delivery;

- a positive PCR of placenta, cord, lesions, or body fluids or a positive silver stain of the placenta or cord

Confirmed Proven or Highly Probable Congenital Syphilis

| Recommended Evaluation | Recommended Treatment |

| • CSF analysis for VDRL, cell count, and protein • Complete blood count (CBC) and differential and platelet count • Long-bone radiographs • Other tests as clinically indicated (e.g., chest radiograph, liver function tests, neuroimaging, ophthalmologic examination, and auditory brain stem response) | 10-day course of aqueous crystalline penicillin of 50,000 units/kg intravenously every 12 hours for infants younger than 1 week of age and every 8 hours thereafter OR Procaine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg intramuscularly in a single daily dose for 10 days |

The entire course of treatment should be restarted if more than 1 day of therapy is missed.

Scenario 2: Possible Congenital Syphilis

Any neonate that had a normal physical examination and a serum quantitative nontreponemal serologic titer less than or equal to the mother’s titer at delivery and one of the following:

- The mother is without a well-documented history of syphilis treatment

- The mother was treated without penicillin

- The mother was treated for syphilis within 4 weeks of delivery

Possible Congenital Syphilis

| Recommended Evaluation | Recommended Treatment |

| • CSF analysis for VDRL, cell count, and protein • CBC, differential, and platelet count • Long-bone radiographs | 10-day course of aqueous crystalline penicillin of 50,000 units/kg intravenously every 12 hours for infants younger than 1 week of age, every 8 hours thereafter a OR Procaine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg intramuscularly in a single daily dose for 10 days OR Benzathine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg intramuscularly in a single dose b |

Scenario 3: Congenital Syphilis Less Likely

Any neonate that had a normal physical examination and serum quantitative nontreponemal serologic titer that is less than or equal to the mother’s titer at delivery and both of the following:

- The mother was treated for syphilis more than 4 weeks before delivery

- The mother has no evidence of reinfection or relapse post treatment

Congenital Syphilis Less Likely

| Recommended Evaluation | Recommended Treatment |

| No evaluation is recommended. | Benzathine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg intramuscularly in a single dose |

Scenario 4: Congenital Syphilis Unlikely

Any neonate that had a normal physical examination and serum quantitative nontreponemal serologic titer that is less than or equal to the mother’s titer at delivery and both of the following:

- The mother was adequately treated for syphilis before pregnancy

- The mother’s nontreponemal serologic titer remained low and stable before pregnancy, during pregnancy, and at delivery

Congenital Syphilis Less Likely

| Recommended Evaluation | Recommended Treatment |

| No evaluation is recommended. | No treatment is required. |

Follow-up examinations and serologic testing is recommended every 2-3 months for all infants with reactive nontreponemal tests until a nonreactive test is obtained. Nontreponemal antibody titers should decrease by age 3 months and be nonreactive by age 6 months for neonates that were not treated for congenital syphilis.

Infants and children aged ≥1 month with primary, secondary, or acquired latent syphilis and with normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tests should be evaluated for sexual abuse through child protection services and managed by a pediatric infectious-disease specialist.

- CDC Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2021

- Government of Canada – Syphilis guide: Treatment and follow-up

- Canadian Paediatric Society – Congenital syphilis: no longer just of historic interest

Epidemiology

General

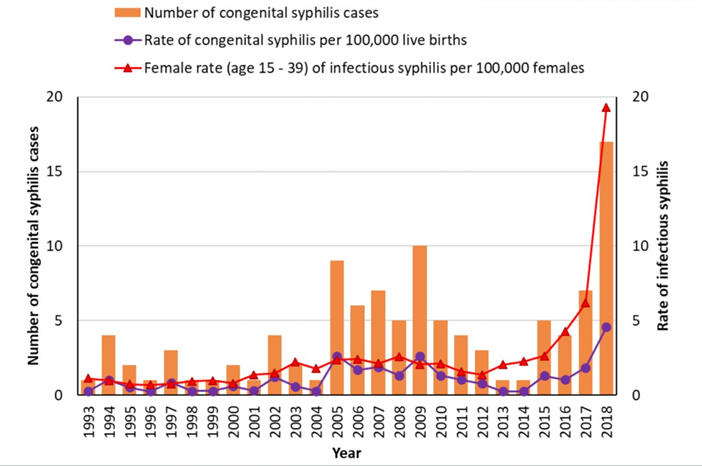

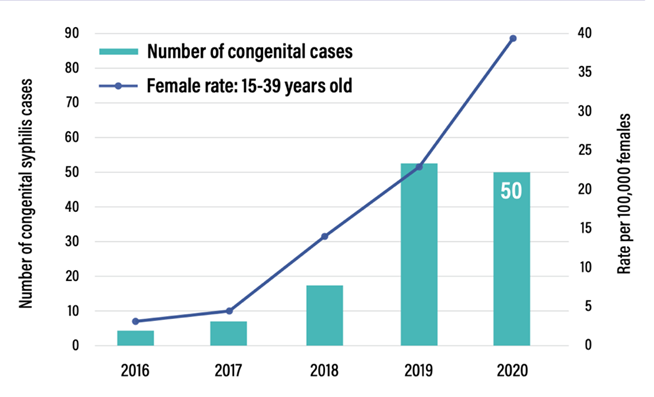

Congenital syphilis is re-emerging and has risen significantly in recent years.

Nearly all provinces and territories experienced significant increases in the rate of syphilis between 2014-2018, with an overall national increase of 151%. In 2016, 4 cases were reported nationally. By 2019, Canada reported 53 cases, and preliminary 2020 data reported 50 cases. Numbers for 2021 and 2022 are higher still: there were 47 cases reported in 2021 in Manitoba alone. This increase has occurred in parallel to the observed rates of infectious syphilis among women 15 to 39 years (see below).

- Government of Canada – Syphilis in Canada: Technical Report on Epidemiological Trends, Determinants and Interventions

- Government of Canada – Responding to Syphilis in Canada (fact sheet)

- PHAC Infectious Syphilis and Congenital Syphilis in Canada, 2020 (infographic)

Incubation Period

The incubation period for congenital syphilis due to transplacental exposure is not clearly defined. Symptoms of early congenital syphilis typically present shortly after birth at three to fourteen weeks of age, but may appear as late as five years after birth. Symptoms of late congenital syphilis usually appear after five years of age but may remain undiagnosed into adulthood.

What is happening with current outbreaks of congenital syphilis infections?

The incidence of congenital syphilis varies across provinces and territories with the majority of cases reported in the Prairies since 2018.

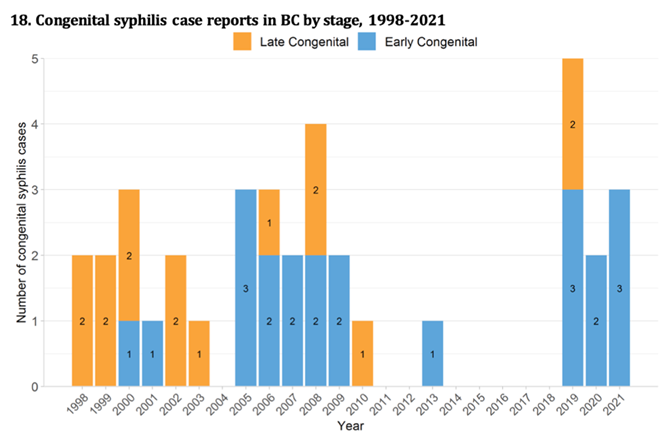

Pacific Region: British Columbia

Between 2010 and 2019, the rates of infectious syphilis increased 6-fold from 3.4 per 100,000 to 21.1 per 100,000. In 2019, British Columbia reported its first 5 cases of congenital syphilis since 2013.

- BC Centre for Disease Control: Syphilis

- Government of Canada – Syphilis in Canada: Technical Report on Epidemiological Trends, Determinants and Interventions

- BCCDC CPS Syphilis Indicators Q4 – 2021

Prairie Region: Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta

MANITOBA

The number of congenital syphilis cases in Manitoba has risen dramatically. In 2015, Northern Manitoba reported its first case of congenital syphilis and in 2017, another case was identified. In 2018, the Winnipeg health region detected its first case of congenital syphilis since 1977. In recent years, the number of congenital syphilis cases has surged. Between 2018 to 2020, Winnipeg detected 60 cases of confirmed or probable congenital syphilis, of which, 8 of these cases occurred in 2018 (0.9 cases per 1,000 live births), 22 cases in 2019 (2.6 cases per 1,000 live births) contributing to 4 syphilitic stillbirths, and 30 cases in 2020 (3.5 cases per 1,000 live births) contributing to 8 syphilitic stillbirths. In 2021, Manitoba recorded 47 cases of congenital syphilis.

- Government of Canada – Congenital syphilis in Manitoba

- CBC News: Manitoba saw nearly as many congenital syphilis cases last year as all of Canada in 2020

- Congenital syphilis re-emergence in Winnipeg, Manitoba

SASKATCHEWAN

Saskatchewan has experienced a steep incline in congenital syphilis cases in the past year. One case of congenital syphilis was reported in Saskatchewan between 2008 and 2017 to the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS). The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health stated in a 2021 news release that 6 cases of congenital syphilis and 2 syphilitic newborn deaths were reported from 2018 to 2020. In 2021, Saskatchewan reported 16 congenital syphilis cases.

- Government of Canada – Syphilis in Canada: Technical Report on Epidemiological Trends, Determinants and Interventions

- Global News – Syphilis is a ‘Tragedy’ in Saskatoon: Medical Health Officer, September 2021

- Saskatoon StarPhoenix – Sask. babies born with syphilis, HIV show gaps in prenatal care: advocates

ALBERTA

The rate of congenital syphilis cases has risen dramatically in Alberta since 2016. Between 2012 and 2016, one case of congenital syphilis was reported. In contrast, a total of 121 cases of congenital syphilis and 28 stillbirths were diagnosed between 2017 and 2020, of which 45 congenital syphilis cases were diagnosed in 2019 and 56 were diagnosed in 2020. In 2016, Alberta declared a provincial outbreak after the rates of infectious syphilis increased from 3.9 per 100,000 in 2014 to 8.8 per 100,000 in 2015. By 2020, the rate of congenital syphilis had increased significantly to 56.7 per 100,000 with 6 stillbirths in the first half of the year.

- Outcomes of infectious syphilis in pregnant patients and maternal factors associated with congenital syphilis diagnosis, Alberta, 2017-2020

- Government of Canada – Syphilis in Canada: Technical Report on Epidemiological Trends, Determinants and Interventions

- Government of Canada – Syphilis in Alberta, 2017-2020

- Edmonton Journal: Six still births in first six months of 2020, Edmonton still in midst of syphilis outbreak

Central Region: Ontario and Quebec

ONTARIO

Ontario has detected a total of 17 cases of early congenital syphilis from 2017 to 2021. One case of congenital syphilis was recorded in 2017, followed by an additional case in 2018, 3 cases in 2019, 3 cases in 2020, and 9 cases in 2021. This corresponds to an increase from 0.1 per 100,000,000 in 2017 to 0.6 cases per 100,000,000 in 2021.

QUEBEC

In the most recent Quebec STBBI report, Portrait des infections transmissibles sexuellement et par le sang (ITSS) au Québec – 2019, the Government of Quebec identified a total of 5 congenital syphilis cases between 2000 and 2015. From 2016 to 2020, the total number of congenital syphilis cases doubled to 10 cases, of which 3 cases were reported in 2016, 1 in 2017, 1 in 2018, 2 in 2019, and 2 in 2020.

Atlantic Region: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador

Between 2008 and 2017, New Brunswick reported two cases of congenital syphilis to CNDSS. According to the two most recent New Brunswick Communicable Disease Annual Surveillance Reports, 1 case of congenital syphilis occurred in 2017 and no cases occurred in 2018.

No congenital syphilis cases were reported to CNDSS by Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador between 2008 and 2017. In 2018, Newfoundland and Labrador reported its first recorded congenital syphilis case.

To date, there have been no reported cases of congenital syphilis in Nova Scotia.

- New Brunswick Communicable Disease Annual Surveillance Reports,

- Government of Canada – Syphilis in Canada: Technical Report on Epidemiological Trends, Determinants and Interventions

- Nova Scotia Health: Public Health warns of syphilis outbreak in Nova Scotia, 2020

Northern Region: Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut

No congenital syphilis cases were reported to CNDSS by Yukon and Nunavut between 2008 and 2017. A recent study examining syphilis in Nunavut between 2012 and 2020 identified zero confirmed congenital syphilis cases.

In 2019, Northwest Territories detected its first case of congenital syphilis since 2009. In an August 2021 health advisory, the Government of Northwest Territories detected two additional cases of congenital syphilis between 2019 and 2021.

- Government of Canada – Syphilis in Canada: Technical Report on Epidemiological Trends, Determinants and Interventions

- Government of Canada – Nunavut, Canada and their management of syphilis, 2012-2020

- Government of Northwest Territories: Rise in Syphilis Rates

What is the current risk for Canadians from congenital syphilis?

Overall risk is low, but significantly higher in the presence of certain factors. Maternal risk factors for syphilis during pregnancy include lack of prenatal care, sexual contact with multiple partners, sex in conjunction with substance use, incarceration, unstable housing, and homelessness. Such risk factors can also be shaped by various social determinants of health including age, gender, ethnicity, experiences of colonial or sexual violence, and socioeconomic status. For example, there is a synergistic interaction between substance use and syphilis epidemics due to their shared risk factors and social forces.

- CDC Syphilis During Pregnancy

- Government of Canada – Syphilis in Canada: Technical Report on Epidemiological Trends, Determinants and Interventions

What measures should be taken for a suspected case or contact?

CASE DEFINITIONS

The Public Health Agency of Canada has developed National Surveillance Case Definitions for confirmed and probable cases of notifiable diseases including congenital syphilis. Only confirmed cases of congenital syphilis are required to be notified nationally. PHAC syphilis case definitions have been defined below:

Confirmed case – Early congenital syphilis (within two years of birth)

Laboratory confirmation of infection in a live birth:

- Identification of Treponema pallidum by nucleic acid detection (PCT or equivalent), fluorescent antibody, or an equivalent examination of material in an appropriate clinical specimen (nasal secretions, skin lesions, fluid from blisters or exudative skin rashes, placenta, umbilical cord, or autopsy clinical material)

OR

- reactive serology (non-treponemal and treponemal) from venous blood (not cord blood) in an infant/child with clinical, laboratory or radiographic evidence of congenital syphilis c

OR

- infant’s RPR titre is at least fourfold higher than the maternal/birthing parent’s RPR titre in samples collected during the immediate postnatal period

OR

- persistent positive treponemal serology in a child older than 18 months of age

AND

- infant/child is under the age of two at the time of meeting the criteria and has no other suspected sources of exposure

Confirmed case – Late congenital syphilis

Laboratory confirmation of infection:

- Identification of Treponema pallidum by nucleic acid detection (PCT or equivalent), fluorescent antibody, or an equivalent examination of material in an appropriate clinical specimen (nasal secretions, skin lesions, fluid from blisters or exudative skin rashes, placenta, umbilical cord, or autopsy clinical material)

OR

- reactive serology (non-treponemal and/or treponemal) in an individual with any clinical, laboratory or radiographic evidence of congenital syphilis c

AND

- infant/child is at least two years of age at the time of meeting the criteria and has no other suspected sources of exposure

Probable case – Early congenital syphilis

- does not meet the criteria for a confirmed case of early congenital syphilis

AND

- reactive serology (non-treponemal and/or treponemal) from venous blood (not cord blood) in an infant/child whose maternal/birthing parent had untreated or inadequately d treated syphilis prior to delivery

AND

- infant/child is under the age of two at the time of meeting the criteria and has no other suspected sources of exposure

Confirmed case – Syphilitic stillbirth

- a fetal death that occurs after 20 weeks’ gestation or in which the fetal weight is greater than 500 g with laboratory confirmation of infection such as the identification of Treponema pallidum by nucleic acid detection (PCR or equivalent), fluorescent antibody, or equivalent examination of material in an appropriate clinical specimen (nasal secretions, skin lesions, fluid from blisters or exudative skin rashes, placenta, umbilical cord, or autopsy clinical material)

Probable case – Syphilitic stillbirth

- does not meet the criteria for a confirmed case of syphilitic stillbirth

AND

- a fetal death that occurs after 20 weeks’ gestation or in which the fetal weight is greater than 500 g where the maternal/birthing parent had untreated or inadequately d treated syphilis prior to delivery

AND

- no other cause of stillbirth is established

Identifying and Reporting

NATIONAL

In Canada, congenital syphilis has been nationally notifiable since 1993. Provinces and Territories are responsible for reporting confirmed cases of congenital syphilis to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) through the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS). Surveillance is conducted through routine case-by-case notification to the federal level.

Data for counts and rates of congenital syphilis have been reported to CNDSS for the following years:

AB, BC, NB, NL, NS, NT, NU, ON, PE, QC, SK, YT: 1993 onwards

MB: 1993-2018

- PHAC National Notifiable Diseases – Syphilis, Congenital

- Government of Canada – Syphilis in Canada: Technical Report on Epidemiological Trends, Determinants and Interventions

PROVINCIAL AND TERRITORIAL

Requirements for reporting congenital syphilis vary by province and territory. The NCCID’s Notifiable Disease Database has compiled detailed information of congenital syphilis reporting policies in all Canadian provinces and territories including official provincial and territorial legislations, regulations, and guidelines.

For more information regarding syphilis, please refer to the following links:

- PHAC Communicable Disease Report Volume 48-2/3 – Syphilis Resurgence in Canada, February/March 2022

- CDC Treatment Guidelines for Congenital Syphilis, 2021

- CDC Syphilis Treatment and Care

- Government of Quebec Numérique de BAnQ archives, Portrait des infections transmissibles sexuellement et par le sang (ITSS) au Québec. 2003 – present.

- Government of Manitoba – Syphilis

- Manitoba Health and Seniors Care – Syphilis Protocol

- BC’s Syphilis Action Plan

- BC Centre for Disease Control. BC experiencing highest rates of infectious syphilis in the last 30 years.

- BCCDC Reportable Diseases Data Dashboard – Syphilis

- Alberta Sexually Transmitted Infections and HIV, 2020

- 2021 Alberta Public Health Disease Management Guidelines – Congenital Syphilis

- Government of Nova Scotia – Annual Notifiable Disease Surveillance Reports

FOOTNOTES

a Neonates born to mothers with untreated syphilis should receive the 10-day course of aqueous crystalline penicillin regardless of whether the neonate’s nontreponemal test is nonreactive, the complete evaluation is normal, and follow-up is certain.

b A complete diagnostic evaluation consisting of lumbar puncture, complete blood count, and long-bone radiography should be normal and follow-up should be certain prior to administering a single-dose benzathine penicillin G regimen. If the results are abnormal, the treatment of choice is the 10-day course of aqueous crystalline penicillin.

c Clinical, laboratory, and radiographic evidence of congenital syphilis includes:

- features suggestive of congenital syphilis on radiographs of long bones;

- reactive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL);

- elevated CSF cell count or protein (without other cause);

- anemia;

- skeletal abnormalities (e.g., osteochondritis, saber shins);

- hepatosplenomegaly;

- skin rash;

- condylomata lata;

- rhinitis (snuffles);

- pseudoparalysis

- meningitis;

- ascites;

- interstitial keratitis;

- lymphadenopathy;

- dental abnormalities (e.g., Hutchinson’s teeth, mulberry molars);

- sensory neural hearing loss;

- intrauterine growth restriction;

- prematurity; or

- any other abnormality not better explained by an alternative diagnosis.

d Note that inadequate treatment for syphilis is a lack of verbal or written confirmation of adequate treatment. Adequate treatment for syphilis in a maternal/birthing parent is defined as:

- treatment with penicillin therapy at least 4 weeks prior to delivery that is appropriate for the stage of syphilis infection;

- a sufficient reduction in maternal/birthing parent non-treponemal titres; and

- no evidence of reinfection.